Vicki Riskin’s Hollywood Legacy

Santa Barbara Writer Recounts Celebrity Parents’ Love Story in ‘Fay Wray and Robert Riskin: A Hollywood Memoir’

By Nick Welsh | Published May 15, 2019

For the last 20 years, Vicki Riskin has been a force within Santa Barbara’s political and philanthropic circles, and she doesn’t show any sign of slowing down now. Famous for knowing everybody whether they’re famous or not, Riskin has a gift of making what otherwise might feel like hard work seem like fun. A genius for connecting people who don’t know each other, she ranks as one of the great synapses in Santa Barbara’s body politic.

After last year’s catastrophic debris flow, when she lost her cousin Rebecca Riskin and her Randall Road home, she joined an effort to transform eight acres of demolished Montecito real estate into a new debris basin. This effort, she hopes, will protect hundreds of downstream residents living in the San Ysidro Creek watershed, where four residents died and 95 homes were destroyed.

Riskin, a former therapist and an accomplished screenwriter — she was the first woman elected president of the Writers Guild of America West — has a reputation for getting things done without having to twist arms. A longtime supporter of Human Rights Watch, Riskin established the Southern California Chapter with a strong branch here in Santa Barbara. She led the charge to make Antioch University a serious player in community affairs, reaching out to Santa Barbara’s Latino community, its veterans, and its community college students. She is probably the person most responsible for getting the Los Angeles–based public radio station KCRW to open a Santa Barbara affiliate. Not coincidentally, it’s located in Antioch’s downtown campus.

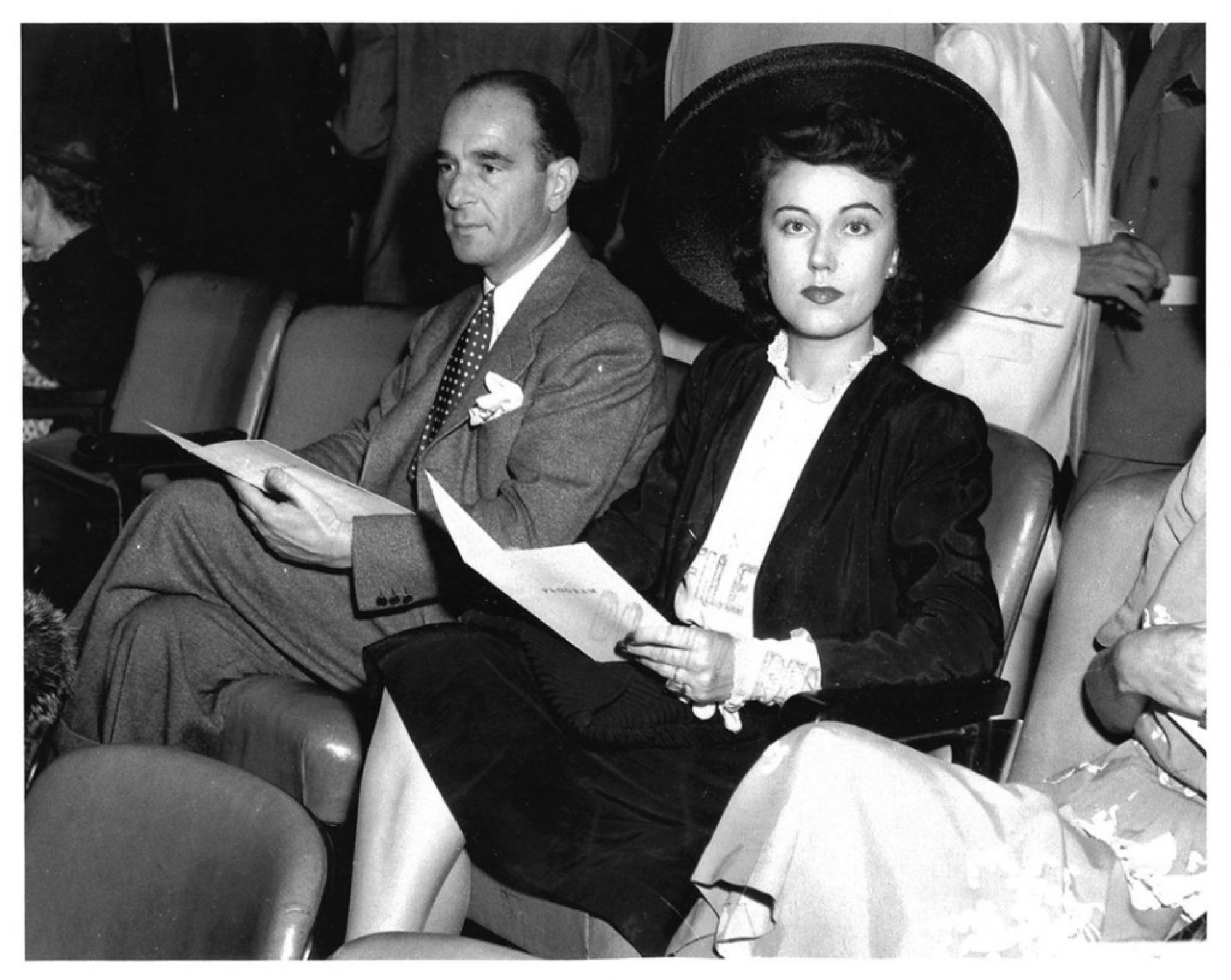

Riskin traces her immediate family’s roots to the big bang moment when sparks first flew between her accomplished parents, then having hit the apex of their creative lives.

Most recently, Riskin has released a charming and engrossing memoir about what appears to have been her magical life. The book was really Riskin’s effort to get to know her world-famous parents — screen actress Fay Wray of King Kong fame and screwball comedy screenwriter Robert Riskin of Frank Capra fame — back before her parents became world famous, back before they were her parents, and all the way back before they’d even met.

In her book, Fay Wray and Robert Riskin: A Hollywood Memoir, Riskin traces her immediate family’s roots to the big bang moment when sparks first flew between her accomplished parents, then having hit the apex of their creative lives. It’s filled with a cast of characters that includes Cary Grant, Harpo Marx, Edward G. Robinson, Carole Lombard, Irving Berlin, Sinclair Lewis, and Howard Hughes to name just a few — neighbors, friends, admirers, poker-playing buddies, and former lovers of her parents.

Riskin, an accomplished writer, knows how to spin a tale, and the book — more spice than dish — is littered with choice morsels. Upon her parents’ marriage, Cary Grant told Riskin’s father, “Be good to her. I was so in love with her,” speaking of Fay Wray. Grant added, “I wouldn’t have been a good husband. I would pay too much attention to the position of the sofa. That sort of thing.”

Riskin doesn’t write just about her life and her memories. She situates this extravagant celebrity circus and the life trajectories of her parents all within the wilder and wider arc of American and world politics. Given everything that went on between the 1920s and the 1950s, that was a whole lot of context to weave in. Riskin managed to make it all feel easy.

It was, of course, anything but.

Who really wants to know who their parents were before their children pigeonhole, sanitize, and straitjacket them into their parental identities? Do we really want to know our parents’ stupid mistakes? Can we forgive them for living lives beyond — or at odds with — the identities we ascribed to them? “I looked at my parents from a different lens,” Riskin explained during a recent interview. “I looked at what was going on in their lives and asked myself how I might have responded,” she said. “It was like an archeological dig. You’d go down one rabbit hole and five other things would pop up. Some things you never could figure out.”

Down the Rabbit Hole

Robert Riskin suffered a stroke when Vicki, the youngest of three kids, was 6. He died when she was 9. That was in 1955. Since then, he’s loomed bigger than life, suspended in the amber of her childhood memories. He was the scent of cigarettes and Old Spice, forever calling out, “Hey, Rascal.”

Yes, but who was he really?

With Fay Wray, Riskin had the perspective of a long mother-and-daughter relationship. But before Wray died in 2004 at the age of 96, the two had transitioned beyond those assigned roles and enjoyed each other as the complicated people they were. Growing up, Riskin learned to navigate Wray’s different personas — a movie star one second, her mother the next. But though she never had to idealize her mother as she had her father, nevertheless, “You never get really curious about your parents until after they die,” she said.

That curiosity led to five years of hard research — spelunking through the caves of family history, dredging through reams of old newspapers, and interviewing old family friends. Riskin got lucky. She stumbled on a lot of new information, information that clarified things, but nothing to change the basic picture. No dark secrets or betrayals emerged. Her mother would remain “a lovely, kind person of steely determination.” As for her father, she said, “I had been emotionally stuck. I had to know my father as a real person. I hope he comes across as a good person, but as a real person, too.”

Riskin’s luck held. She rediscovered just how much her parents loved each other. It was a love that jumped out of its own skin — voracious, tender, and fun. During World War II, Robert Riskin wrote a treasure trove of letters to his wife when he was away, producing 26 government propaganda films designed to reassure German citizens about how American troops behaved as an occupying force.

Riskin’s letters are lengthy and witty. “First off, I love you,” Robert starts off in one. “I must stop talking about you. I’m getting to be a bore. I haven’t seen that awful look on people’s eyes yet — you know that fixed expression that struggles to evoke interest but actually says, ‘God, there he goes again …’”

Wray’s letter-writing style tended to an almost anthropological precision. In the 1950s when Robert suffered a paralyzing stroke, she wrote, “You run your hand along my upper arm. I say, ‘I’m here. You are wonderful.’ You stretch your arm high and let it fall down over my shoulder. I sink down close to you and your arm holds me close, your hand feeling my face and stroking it.”

Wow.

The crazy intersection of family histories … stood out as the most randomly wonderful and optimistically American story.

Fay Wray and Robert Riskin were a Hollywood love story, but the crazy intersection of their family histories — the collision of a girl from a hard-scrabble Mormon mining town in Utah who was frequently described as both innocent and sensual with the wise-cracking son of Russian Jewish immigrants from New York’s Lower East Side — stood out as the most randomly wonderful and optimistic American story: something straight out of a Robert Riskin screenplay.

Going Out West

Fay Wray headed west in 1920 from Lark, Utah, at age 14. Her mother, Vina, described as having “an impudent kind of beauty,” got a college degree when few women did. Riskin describes her grandmother Vina as a mix of “granite, imagination, and emotional fragility,” a legendary Mormon missionary’s daughter who left her first husband, citing an unconsummated marriage, and wed another. In Mormon country, this was cause for scandal, and newspapers wrote about it.

It’s likely Wray’s mother suffered from a bipolar condition. At one point, she checked herself into an asylum. Home life was anything but sweet. The family — which grew to six kids — moved from Alberta, Canada, to Mesa, Arizona, to Salt Lake City, to Lark, the latter described by a friend of Wray’s as “the last place God made and he forgot to finish.”

Wray’s father struggled to find his way but never succeeded. By the time Wray was 12, he would leave, never to be heard from again. That same year, Wray’s older sister — with whom she shared a bed — died of the flu. Two years later — at age 14 — Wray found herself on a train bound for Los Angeles, accompanied by a 21-year-old family friend, a photographer with romantic dreams. A year later, the rest of the family — Wray’s mother and four siblings — followed suit.

Along the way, Wray succeeded in falling into the movies, perhaps, Riskin suggests, with the help of her photographer-chaperone. Looks, personality, and talent helped too. So, too, did an iron-clad work ethic. Wray worked for Hal Roach and for Carl Laemmle, then big names in the world of film. By the time she was 18, Wray had become the family breadwinner. By 19, she was making the equivalent of $350,000 a year.

Wray, of course, is best known for her role as the love interest in King Kong, the “beauty” who eventually “killed the beast.” But Wray’s film career spanned across 120 films, sometimes as many 10-12 per year. The pace was grinding and the work was not for the faint of heart. In King Kong, made in 1933, Wray was ordered to scream into a microphone for eight hours straight. Another day, she worked 22 hours. On another film, Wray found herself slapped 20 times across the face before the director got the right take. Talent was critical. Durability, no less so.

As an actress, Wray inevitably had to navigate sexual advances from men in power, like director Erich von Stroheim, in whose bank-busting epic Wedding March — he had 50,000 handmade apple blooms glued to trees — she starred. When Darryl Zanuck offered her a three-picture deal, he expected Wray to sleep with him. When she refused — fleeing in tears — he canceled the contract.

One of the few arguments Riskin remembered having with her mother was over the sexual harassment described by Anita Hill during the confirmation hearings of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas in 1991. “I thought Anita Hill was so brave,” Riskin recalled. “But she [Fay Wray] said, ‘I don’t think she [Hill] should say these things in public.’ That’s not the way she handled it. That was not dignified.”

Mr. Riskin Goes to Hollywood

Robert Riskin, by contrast, grew up on New York’s Lower East Side, the son of Jewish immigrants from Belarus. His grandfather, the story went, had stolen a horse from a Cossack soldier and then tried selling it back to him. No one knows if the story was true; they just knew a good story when they heard one. Robert Riskin’s father was a tailor and a garment worker, an enthusiastic free thinker who read socialist newspapers written in Yiddish, supported labor unions, and was a champion of the working man. He was outspoken in his opposition to marriage, arguing it destroyed true love, but given the frailties of the human species, he conceded, it might be a necessary evil.

At age 13, Robert Riskin dropped out of school. By selling newspapers on the street, he accumulated enough money to rent a typewriter for three months. He wrote stories and poems. He ghostwrote love letters for neighbors. By age 15, he was ghostwriting love letters for his boss. It’s not clear how helpful his letters were. By 17, Riskin — a snappy dresser with snappy patter — was making comedic film shorts for Klever Komedies. His plays were getting produced, and he was living the high life. By age 20, he was rooming with actor Edward G. Robinson, who was then just beginning his illustrious acting career.

When the bottom fell out of the stock market in 1929 precipitating the Great Depression, Riskin couldn’t find work. In 1930 — at age 33 — he headed west to Hollywood. Almost immediately, he was offered $7,500 for one of his stories. He held out for $30,000 and got it. In short order, he connected with Columbia Studios movie producer Harry Cohn, infamous for flipping his lid and chasing after women whether they were interested or not.

Actress Carole Lombard, described by Riskin as smart, tough, and profane, famously said, “Look, Mr. Cohn, I’ve agreed to be in your shitty little picture, but fucking you is not part of the deal.” Cohn reportedly replied, “That doesn’t mean you can’t call me Harry.”

In today’s #MeToo climate, Cohn would be on par with Harvey Weinstein. Even then, it was cause for concern and not everyone put up with it. Actress Carole Lombard, described by Riskin as smart, tough, and profane, famously said, “Look, Mr. Cohn, I’ve agreed to be in your shitty little picture, but fucking you is not part of the deal.” Cohn reportedly replied, “That doesn’t mean you can’t call me Harry.”

Robert Riskin and Lombard became a hot romantic item, and the Hollywood press constantly speculated about when they’d get married. Somehow, it never happened.

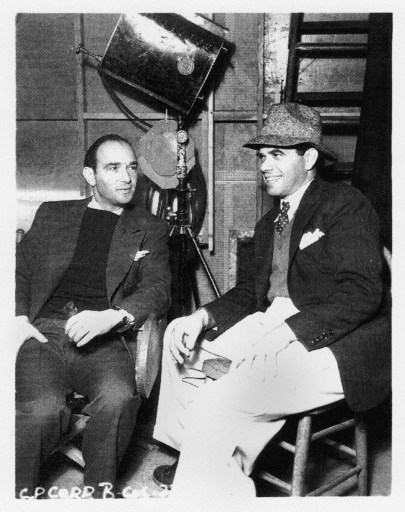

“Natty, witty as can be, he loved life, sports, and women, and vice versa,” explained Frank Capra, the director with whom Riskin would do his best-known work. He and Capra formed a rare creative partnership, working together on such classics as It Happened One Night, Meet John Doe, and Mr. Deeds Goes to Washington. Politically, Riskin and Capra made a decidedly odd couple, Capra a conservative Republican and Riskin a New Deal Democrat. Artistically, they finished each other’s sentences. Capra described it thusly: “Our funny bones vibrated to the same tuning fork.”

(As Frank Capra got older, he grew more insistent about claiming all the credit for his films. At one point, he would exclaim, “Fuck the writers.” Even in his prime, Capra insisted on top billing, placing “A Film by Frank Capra” above the title. Not surprisingly, Capra’s autobiography is titled The Name Above the Title. Just as not surprisingly, Vicki Riskin has objected. Films, she argued, are inherently collective enterprises. Little wonder that during her tenure as head of the Writers Guild, Hollywood banned the use of “A Film By.”)

It Didn’t Happen One Night

Robert Riskin liked smart, funny women — tough survivors with soft hearts. He populated his screenplays with them, and they drove his plots. He also liked decent John Does, guys far more decent than they ever were clever. Riskin never shied away from sentimentality. In his scripts, the little guy always prevailed. Cynics and totalitarians never did. No one was beyond redemption, though, not even the fat-cat bankers. The bad guys — at least some of them — would see the error of their ways. And suffused throughout, there was always a message: hope.

But the dialogue had to pop. Riskin’s always did.

The first time Riskin and Wray met was 1937. He was playing tennis, and she wanted a part in a movie he and Capra were about to make. The exchange was over before it started. At the time, Wray was married to John Monk Saunders, an astonishingly good-looking screenwriter. Saunders was a Rhodes scholar, a star athlete, and a flying ace. As Vicki Riskin tells it, he was all about fancy, long roadsters and even longer kisses. Her mom was a swoon. They had a daughter, Susan, together. But naturally, Saunders would prove too good to be true, and Wray spent most of their nine-year marriage discovering just how untrue he was. Saunders was a serious drunk and an even more serious cheat. Wray wound up hiring William “Wild Bill” Donovan — who later headed the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency — as her attorney in a painful custody battle that she eventually won. Later, Saunders would hang himself in some dingy boarding house room. Wray, according to her daughter, always wished she could have helped him more. “She thought he had ‘a serious weakness,’” Riskin said. “That’s what she called it.”

The next exchange between Robert Riskin and Fay Wray took place at a Christmas party in 1940. This time, sparks flew. Both ways. Riskin was clearly smitten, but Wray was involved with playwright Clifford Odets, later persecuted by the federal government for his communist affiliations. After she and Odets broke up, she had a brief romance with the fabulously wealthy Howard Hughes, then making airplanes as well as movies.

By 1942, at last, the clouds of romantic opportunity parted and what was meant to be was allowed to become. Robert Riskin and Fay Wray got married in New York City. In attendance were Irving Berlin, Wild Bill Donavan, and William Paley, who would later become head of CBS.

That’s a Wrap

Recently, Vicki Riskin has been making the book tour circuit. Last year’s debris flow effectively chased her out of town; she and her husband, screenwriter David W. Rintels, are now living on Martha’s Vineyard. In person, Riskin is down to earth, comfortable, and accessible. She expresses her judgements of local political personalities with care and precision. Politically, she remains drawn to rumpled, progressive Democrats like her friend, Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown, whose down-home, wonky populism manages to resonate with displaced workers even in the heart of Trump country. Brown toyed with running for his party’s presidential nomination, but he opted not to, making him a statistical anomaly.

When Brown talks about Vicki Riskin, you’d think he was describing a character in one of her father’s movies. “She’s always upbeat about what’s going on in her life, even after the disaster,” he said. “She never complains, and people are attracted to her sense of optimism.” When asked to describe Riskin’s politics, he cited her work in Human Rights Watch. “No one’s better than anyone else,” he added. “She just sees the world like that. Her kindness, her empathy, and egalitarianism all come through.”

When asked what her father would be doing if he were alive today, Riskin joked he’d be writing for TV shows like Cheers or maybe a film like Moonstruck. “In the 1930s, women were the driving force in screwball comedies,” she said. “Today, I don’t know — they’re not making so many good comedies.”

Of all her father’s movies, the one that resonates with Vicki Riskin the most is Meet John Doe, starring Gary Cooper and Barbara Stanwyck. In it, she said, an unscrupulous media mogul tries to whip the country into a right-wing populist frenzy. “It’s his darkest movie,” Riskin said. “That was very prophetic. That’s Rupert Murdoch.” It has a happy ending though. “When you give people the truth, they’ll figure out what’s right. There are so many parallels with what’s happening now,” she said. “When people are suffering, they’re vulnerable to manipulation out of fear.” But Riskin remains steadfast and optimistic. “I turn back the clock and we got through that,” she said. “So we’ll get through this.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.