In Cryonics Lawsuit, Son Fights for Father’s Frozen Head

Kurt Pilgeram Alleges Alcor Life Extension Wrongfully Decapitated One of Its Biggest Believers

By Tyler Hayden | Published April 24, 2019

In Cryonics Lawsuit, Son Fights for Father’s Frozen Head

Kurt Pilgeram Alleges Alcor Life Extension Wrongfully Decapitated One of Its Biggest Believers

By Tyler Hayden | Published April 17, 2019

Dr. Laurence Pilgeram didn’t believe in heaven, but he did believe in life after death.

In 1990, at the age of 66, Pilgeram signed a contract with the Alcor Life Extension Foundation to freeze his body upon his death with the hope that, decades or centuries from now, medical science would resurrect him. Alcor, headquartered in a sand-colored business park in Scottsdale, Arizona, offers two types of “cryonic suspension” services: full-body for $200,000, and head-only for $80,000. It’s a bargain for a shot at immortality. Clients typically pay by signing over their life insurance policies.

The head-only option, the company explains, is the most cost-effective way to preserve a patient’s identity; using future nanotechnology, a new body might be grown around the brain. But Pilgeram never liked the idea of “Neurocryopreservation,” his family has said, so he chose “Whole-Body Cryopreservation” by initialing the appropriate box in the contract with his characteristically ornate handwriting. He also requested that Alcor freeze all of his remains, regardless of any damage caused to them by trauma or decomposition.

In 2015, when Pilgeram was 90 years old, he died of an apparent heart attack on the sidewalk in front of his Moreton Bay Lane home in Goleta. Alcor was contacted and preparations for Pilgeram’s suspension began. But things didn’t go as planned. Alcor dispatched two of its technicians to the morgue, where they removed Pilgeram’s head, packed it on ice, and drove it back to Scottsdale. The rest of his remains were cremated and mailed to his son Kurt in Montana.

When Kurt demanded to know why his father’s whole body hadn’t been preserved, he received conflicting accounts from Alcor, according to court records. First, the company said Laurence’s body had decayed beyond saving. Then, it claimed he hadn’t kept up with his yearly $525 membership dues. Finally, it suggested the technicians didn’t want to wait for the permit necessary to transport a full body across state lines.

Not satisfied with any of those answers and incensed by what he considered a dismissive attitude by Alcor throughout the process, Kurt blocked the payout of his father’s life insurance and demanded the company relinquish his head. Alcor refused and sued Kurt for the money; Kurt sued back. Thus began a tangled, four-year legal battle that will go to trial in Santa Barbara Superior Court next year.

The case has ballooned beyond the initial dispute, and now there’s major money at stake. Using the Pilgeram incident as a springboard, Kurt’s lawyers intend to challenge the validity of the entire cryonics industry by questioning its basis in science and the promises it makes to customers. “The more we learn, the more we ask ourselves, does the model itself work?” said attorney David Tappeiner with Santa Barbara law firm Fell Marking. “This case is a lot bigger than we thought.” If they win, it could put Alcor out of business.

Alcor, a multimillion-dollar nonprofit and the biggest cryonics operation in the world, is now lawyered to the hilt, too. The company declined to comment beyond a prepared statement that alludes to past legal disputes, perhaps its recent one with the family of baseball legend and Alcor client Ted Williams. “Alcor,” wrote attorney James Arrowood, “is confident that the Court and, if necessary, a Jury, will properly weigh all the facts and, as they have in the past, find that Alcor has acted appropriately pursuant to its obligations to its members and patients.”

Playing God

Even as a little boy, Laurence Pilgeram thought a lot about death. He wanted to understand it, and to beat it.

When he was 5, Pilgeram visited a relative in the hospital and later attended their funeral. He wondered why doctors were so helpless against disease. At 7, during a Saturday-night town dance, he sat alone and preoccupied with the thought of losing his parents. “Images would enter my mind of a loved one ever so still and silent in a coffin never again to join us and unaware of the beings and life around the casket,” he wrote in a self-published autobiography. It filled him with dread because Pilgeram, who was raised Catholic, had stopped believing in an afterlife about the same time he’d stopped believing in Santa Claus.

By 14, Pilgeram was studying the embalming process of Egyptian mummies and pondering the split-second transition from life to death. The concept was constant and concrete, as livestock were frequently slaughtered on his family’s ranch in Eden, Montana, where his German forebears had settled in the late 1880s. While other young men his age were establishing their own ranches, Pilgeram was saving up his fur-trapping money to buy books on tissue culture and organ transplants. “He was always just a little bit different,” said his younger brother, Jim. “He got along with everybody and had a lot of girlfriends, but he was always just a little different. Our mother used to joke that he was dropped from outer space by aliens.”

“Our mother used to joke that he was dropped from outer space by aliens.”

— Jim Pilgeram

Pilgeram built a laboratory in a corner of his parents’ barn, complete with a hand-crank centrifuge and a car-battery-powered electrical system, where he experimented on animals and tried to prolong their lives. He injected bovine growth hormone into guinea pigs but only succeeded in giving them diabetes. He fed thyroid tablets to the old family dog, Tommy, who regained some of his youthful energy and even started chasing lady dogs again until he was shot by a neighbor for harassing his livestock.

For his most ambitious test, Pilgeram, inspired by a radio series on experimental biology produced by UC Berkeley, injected fertilized chicken-egg embryos into adult chickens. He killed three of them before his mother found out. Still, he was determined to keep following what his brother called his “inquisitive streak.” “He wasn’t much for the country way,” Jim said.

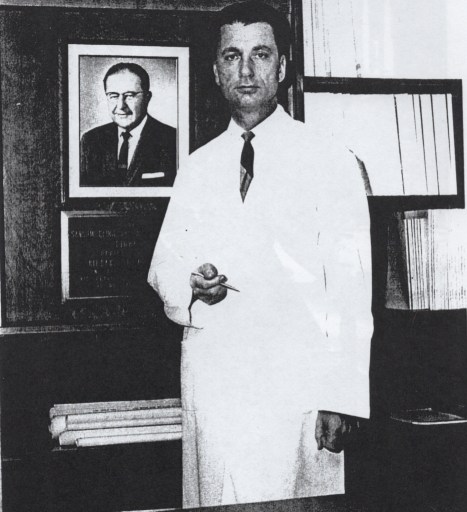

Pilgeram graduated high school and enrolled at Berkeley, where he got his PhD in biochemistry in 1953. He wanted to devote his career to researching the aging process but quickly discovered it was a field of low standing among scientists. “It was as though the topic was relegated to the province of fools and incompetents,” a frustrated Pilgeram wrote. He chalked it up to “mankind’s unquestioning acceptance of death as being inevitable.”

He made an end-run by choosing to study vascular disease, a respected field still connected to aging. His plan was to research heart attacks and strokes and, whenever possible, consider the results through the lens of aging. “It was killing two birds with one stone,” he said.

After teaching in Chicago and running a lab in Minnesota, Pilgeram was recruited by Sansum Clinic in Santa Barbara to direct its atherosclerosis research program with a promise to build him a new research facility on Bath Street. In July 1965, Pilgeram moved to town with his wife, Marylin, and their two young sons, Kurt and Karl. They were welcomed at a swanky buffet dinner at the Hope Ranch Country Club, and soon Pilgeram settled into the new Bath Street building, which he helped design and still stands today. The job didn’t last — Pilgeram resisted Sansum’s order to shift his focus to diabetes — and neither did the marriage.

It was around this time that Pilgeram first became interested in cryonics. While he makes no mention of it in his 125-page autobiography, Jim recalls the topic coming up frequently during Pilgeram’s summer trips back to the family ranch. He’d tell everyone he wanted to be frozen when he died. They should too. He’d argue that their German family line, which he traced back to the 1300s and said produced a number of great thinkers like himself, ought to be protected.

The relatives all refused. “The rest of us just thought, hell, if we’re lucky enough to have one good life, that’s all we deserved out of it,” said Jim, now 87. The debates were usually civil, but sometimes they escalated. Their mother was especially against the idea, Jim said. “She’d tell me, ‘Jim, don’t let your brother freeze me.’”

“A vital part of my life has been taken from me by this evolutionary outrage called death.”

— Laurence Pilgeram

With respect to the lawsuit, Jim was adamant Pilgeram wanted his whole body preserved. “He believed in cryonics, but he didn’t believe in mutilation,” said Jim, who gave a deposition to the same effect. “He made it awful plain to them people that he did not want to be just a head.” He recalled teasing Pilgeram about Alcor’s cheaper suspension option. “Hell, they’re going to put your head on a coyote and stick you in the circus,” he’d say. Plus, Jim went on, Pilgeram was a boxer and a tap dancer and always kept in good shape, even in his later years. He was proud of his body. He’d have wanted to keep it.

Pilgeram remarried to a woman named Cynthia Moore in 1971, the same year he started giving talks at cryonics conferences around the country. One of his favorite memories of Cynthia was seeing the movie Dr. Zhivago together under the starry ceiling of the Arlington Theatre. The lyrics to “Lara’s Theme” felt prophetic: “Somewhere, my love, there will be songs to sing, although the snow covers the hope of spring. … Someday we’ll meet again, my love. Someday, whenever the spring breaks through, you’ll come to me, out of the long-ago, warm as the wind, soft as the kiss of snow.”

Cynthia’s death in 1990 hit Pilgeram hard. His writings about it reflect a seething pain and anger. “A vital part of my life has been taken from me by this evolutionary outrage called death,” he fumed.

Pilgeram donated Cynthia’s body to Alcor through the Anatomical Gift Act, which normally only applies to medical research or organ harvesting. She was deposited in one of Alcor’s giant, liquid-nitrogen-filled vats cooled to a frigid -321 degrees Fahrenheit, each one containing four full bodies surrounding a central column of eight to ten heads stacked in Crock-Pot-sized canisters. But in 1994, a California appellate court ordered Alcor to hand Cynthia’s body over to her family after her sister found a copy of Cynthia’s will. She’d wanted to be buried.

Meanwhile, Pilgeram continued a long and successful career that won him several awards and earned him a prestigious position at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston. He eventually settled into retirement in Goleta, where son Karl still lives. His work introduced him to a number of prominent politicians as he jockeyed for National Health Institute funding, including Hubert Humphrey, who remained an ally in securing him government grants over the years.

As recently as 2010, Pilgeram published a research paper through UC Santa Barbara that identified ways to flip a key biochemical switch in the aging process. And in at least one way, he already lives on. UCSB’s Laurence Pilgeram Biology Aging Fund is flush with nearly $900,000.

Tip of the Iceberg

The concept of cryonics — not to be confused with cryogenics, the branch of physics that studies the effects of very low temperatures on inert materials — entered public consciousness in 1967 with news of the world’s first “cryonaut,” a 73-year-old psychologist from Glendale. Since then, it’s stoked equal amounts of curiosity, revulsion, and legitimate scientific study. Critics, of which there are many, call it a scam that takes money from desperate and gullible people. Proponents, like Alcor, are always ready to counter.

First, they emphasize, no one promises cryonic suspension will work. The service is full of disclaimers and is essentially a long-term experiment to see if medical science can catch up with the fantasy of a second life. Why not give yourself the chance? There’s also the possibility of one day mapping a brain’s neural network and uploading all the electrical connections to a computer. In 2015, a 23-year-old woman who died of cancer gave her head to Alcor with that specific wish.

Supporters say there’s significant precedent for the freeze/thaw theory. Human embryos are frozen and warmed back up in fertility procedures. Certain species of fish survive entire winters encased in iced-up lakes. Recently, a scientist was able to put a rabbit kidney into suspension, thaw it, and transplant it back into the rabbit, and five dozen researchers, including from MIT, Harvard, and UCLA, have signed a petition saying there exists a “credible possibility” of cryonic success.

Even as far back as 1980, Laurence Pilgeram discussed, in a strongly worded letter to the California State Cemetery Board, how a cat’s brain had been frozen and partially resurrected in Japan. He’d taken great issue with the board describing cryonic suspension as “consumer fraud” during a meeting in Santa Barbara.

The possibilities offered by the budding field of nanotechnology are especially enticing to cryonicists. “Cells will be reprogrammed to heal severed spinal cords, regrow lost limbs, and even regenerate new organs,” Alcor says on its website. “This kind of tissue regeneration already occurs naturally in children that lose fingertips, and in organs such as the liver.” Perhaps most importantly and most basically, no one knows what the future will hold. Fifty years ago, the production of an artificial kidney was inconceivable. Who’s to say what we’ll be capable of in another 50 years? Or 500 years?

Still, the afterlife industry remains on the fringes. There are only about 300 people preserved in the U.S., 164 of them at Alcor, which also warehouses 33 unwitting pets. Around 1,400 more people are signed up for suspension with an average of one or two checking into Scottsdale every month. The vast majority of clients are men. Among them are a TV sitcom writer, a casino owner, and a Silicon Valley venture capitalist. The youngest patient is a 3-year-old girl.

Alcor, named after a faint star in the Big Dipper, chose Arizona because the region is generally safe from natural disasters and has lax regulations for its line of work. Its Patient Care Bay is protected behind bullet- and bombproof walls in case of a terrorist attack. Its only real competitors are the Cryonics Institute near Detroit and CryoRus outside Moscow, which host around 100 and 50 corpsicles, respectively.

The place is run by longtime director and futurist Max Moore, who has plans to expand the facility to accommodate 1,000 more suspensions. A couple of years back, he installed blue floor lighting below the patient vats to give the room a more “science-fictiony” look, he told a reporter. In the same interview, Moore challenged the idea that the organization is freezing dead bodies. “[Alcor’s patients] are basically in a deep coma, but without any metabolism,” he said.

The scientific community at large maintains cryonics is a bad bet. The medical technology needed to awaken a dead person isn’t even a dot on the horizon. The idea of uploading consciousness to a computer is just as far-fetched. At present, it would cost billions of dollars and take thousands of years to properly map even a single person’s brain.

That’s not to mention that the main process behind cryogenic freezing, called vitrification, may not even work. Before they lower patients into their liquid nitrogen bath, Alcor pumps a chemical cryoprotectant, a sort of human antifreeze, through their veins, which turns into a glassy substance so that ice crystals can’t form and destroy tissue cells. But that glassy substance is known to crack and break. Even if that worked, what other untold complications, from physical to mental, would result from reanimation, from waking up in a different era with no friends or family or money?

More practically, what happens if Alcor runs out of money or its facilities shut down? Critics frequently cite the Chatsworth Scandal of 1979, when nine cryonic patients were abandoned and left to rot in an underground crypt at the Oakwood Memorial Park Cemetery in Chatsworth, California. “The stench near the crypt is disarming,” a reporter famously wrote. “It strips away all defenses and spins the stomach into a thousand dizzying somersaults.”

Cold-Blooded

Despite his father’s best efforts, Kurt never bought into cryonics. He and his brother weren’t allowed to watch TV growing up, and instead Pilgeram would give them research papers to read, sometimes on his favorite subject. Kurt even recalls as a 9-year-old visiting Alcor’s original office in Riverside with his dad. The front door was locked, so they circled around back and noticed a large rectangular box wedged under the carport. Inside was Alcor’s first female patient in deep subzero sleep. “She was just sitting there,” Kurt scoffed. “Even at that age, I knew something was wrong. Any dog could have just walked up and lifted its leg.”

Kurt moved to Santa Barbara when he was 5 years old and graduated from Dos Pueblos High School. He did a year of junior college in Oxnard before loading up his truck near his 21st birthday and heading up to the Pilgeram homeland in Montana, where he lives today, selling Mac tools. He may not have followed in his father’s footsteps or believed in bringing people back from the dead — “You can’t make a cow out of hamburger,” he declared — but with respect to the lawsuit, it doesn’t matter.

“What the family believes, what I believe, what you believe — none of that is important,” Kurt said. “What is important is what my dad wanted.” The closest Kurt can get to that now, he believes, is to cremate his father’s head, reunite it with the rest of his remains, and scatter the ashes at the ranch. “I don’t think that’s too much to ask.”

“You can’t make a cow out of hamburger.”

— Kurt Pilgeram

Alcor’s entire business model is predicated on unrealistic expectations, Kurt said. For a dead patient to be properly preserved, the company itself admits, he or she must be immediately dunked in an ice bath, then flash-frozen as quickly as possible in Alcor’s operating room. In fact, ideally, they’d pass away in a Scottsdale hospice, where Alcor staff would be waiting right outside the door. But that rarely happens, Kurt points out.

Alcor’s patients are scattered all over the country, and it takes time for arrangements to be made, especially if they die unexpectedly. In Pilgeram’s case, he sat for five days in a regularly chilled morgue and vehicle before his head was finally ensconced in its liquid nitrogen container. “Alcor’s so-called grand experiment is set up to fail,” Kurt said.

He also noted that there are no medical doctors on Alcor’s roster. The people sent to perform the “neuro-separation” on his father hold degrees in fine art and business administration. They’re allowed to do what they do because in the eyes of the law, cryonics are treated as elaborate funeral arrangements.

Alcor’s people have been anything but honest or apologetic about the matter, Kurt claimed. Communication was nearly nonexistent from the start. “Why didn’t Alcor just pick up the phone and say, ‘Guys, we really messed up?’” Kurt asked. “I would have worked with them on that. There were so many opportunities this could have been fixed. They haven’t been regular folks.”

Kurt’s brother, Karl, was originally party to the lawsuit. But after Alcor threatened to disinherit the brothers from their father’s estate — a hyper-aggressive intimidation move by Alcor that a judge quickly dismissed — Karl settled with the company for an undisclosed amount.

Kurt wants to keep fighting. He’s flown out to Santa Barbara for every court hearing, no matter how minor. “They’re used to bulldozing people out of the way,” he said. “I’m not that kind of person.”

He’s suing not just for his father’s head and the life insurance money, but also for punitive damages from what he described as chronic anxiety and stress he’s felt since receiving his dad’s ashes in the mail and the subsequent litigation threats lobbed his way by Alcor. “They’ve taken this way too far,” he said. “It’s the principle of the thing. It’s just so wrong.”

As a legal matter, Kurt and his attorneys may have a difficult time convincing a jury that Alcor should relinquish the head. It could set a dangerous and unfair precedent that family members of Alcor patients who disagree with their loved one’s final wishes would be able to simply sue for the remains and the money promised to the company.

Alcor is also likely to seize on the fact that it took two years for Kurt to formally ask for his dad’s head. The company might argue Kurt was waiting for his inheritance to be finalized before making his move. Kurt said he simply didn’t know how to proceed.

“You don’t just Google ‘My dad lost his head and who’s a good lawyer,’” he said. “I’ve lost a lot of sleep over this; there’s no doubt about it. But this has fallen to me, so I’ll do whatever I need to do to make it right.”

Pints for Press | This article’s author, Tyler Hayden, will discuss the reporting and writing of this story with editor Matt Kettmann on Wednesday, April 24, 5:30 p.m., at Night Lizard Brewing Company in the Santa Barbara Independent’s third Pints for Press event. Buy a pint and $1 goes to supporting our journalism. See independent.com/pintsforpress.

You must be logged in to post a comment.