His parents named him Oswald Joseph Da Ros. But as far as the community was concerned, his middle name was “integrity.” Ozzie Da Ros’s legacy in Santa Barbara was not only the buildings and structures that you see, but the standard to which they were built.

Ozzie was born in Santa Barbara in 1921 to Italian immigrants Marianna Mautino and Antonio Da Ros; his father was a stone mason who had built brownstone houses as well as tunnels under the Hudson River. Around 1915, Antonio Da Ros had moved to Santa Barbara, where masons were greatly in demand, as there was a keen interest in the work of European craftspeople. Antonio Da Ros apprenticed under two of the most famous — Peter Poole and R. Wood — working on the iconic walls in Mission Canyon, balustrades on Alameda Padre Serra, Plaza Rubio, the stone house on Padre Street, and the McCormick estate.

Antonio then trained his young son Ozzie in the tradition of the Italian masons. Ozzie started early, helping out on the job sites, such as the all-stone addition on Samiramis (Eaton House) and Wallace Frost’s estate. Ozzie was even allowed to get a special driver’s license at the age of only 14 so that he could become the timekeeper and apprentice at the building sites after school hours and on Saturdays.

It was important that Ozzie learned the craft with the original hand tools of the trade — wooden mallets and carving tools, which underlie the industry — and he began working while still in high school.

Ozzie worked under other craftspeople, such as the Scottish stonecutter Andrew Phillips. Ozzie also trained with Albert Arata (one of the finest stonecutters who also did entablatures — lettering on masonry) and helped to hand-carve the beautiful letters we see on the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

Ozzie was selected to work on the Ganna Walska Lotusland estate. Recognizing her perfectionistic spirit, Ozzie took her to San Marcos Pass to hand-select the boulders for her first new garden.

A renowned opera diva, Walska was a woman of artistic temperament and high expectations. In Ozzie she recognized a kindred spirit in terms of his demand for quality, but she also learned that Ozzie was straightforward and uncompromising in his standards. “I like you, Ozzie,” said the indomitable Walska, “because you’re never my ‘yes man.’”

When Walska wanted to create her Japanese garden, she dismissed three Japanese landscape architects and insisted Ozzie take over the design. He refused and told her Frank Fujii — already on her staff — was the man she should use. This was the kind of integrity Ozzie maintained — no ego, just honest appraisement as to who would be the best man for the job she needed. So Ozzie worked with Frank to create the Japanese Garden, utilizing boulder blocks weighing 10-12 tons.

Famed architect Lutah Maria Riggs hand-selected Ozzie in 1958 to work on the Donohue estate in Los Angeles. During the 1960s, Da Ros created the stonework in the Montecito Village on San Ysidro Road.

Ozzie worked on so many of the iconic structures of Santa Barbara — from Museum of Natural History to La Arcada, from restoring the pool at Casa del Herrero and creating the 9/11 memorial at Our Lady Of Sorrows to converting the hand-hewn stone walls of the old packing house to become Birnam Wood. He even built the Santa Barbara Historical Museum — producing the adobe bricks in his own backyard.

In 1952, Ozzie was part of the legendary team of experts restoring the facade of the Old Mission. After the earthquake in 1925, the mission had been repaired using a stone veneer over a strong concrete base. However, the mortar contained aggregate stone that reacted with the acidic soil and began decomposing.

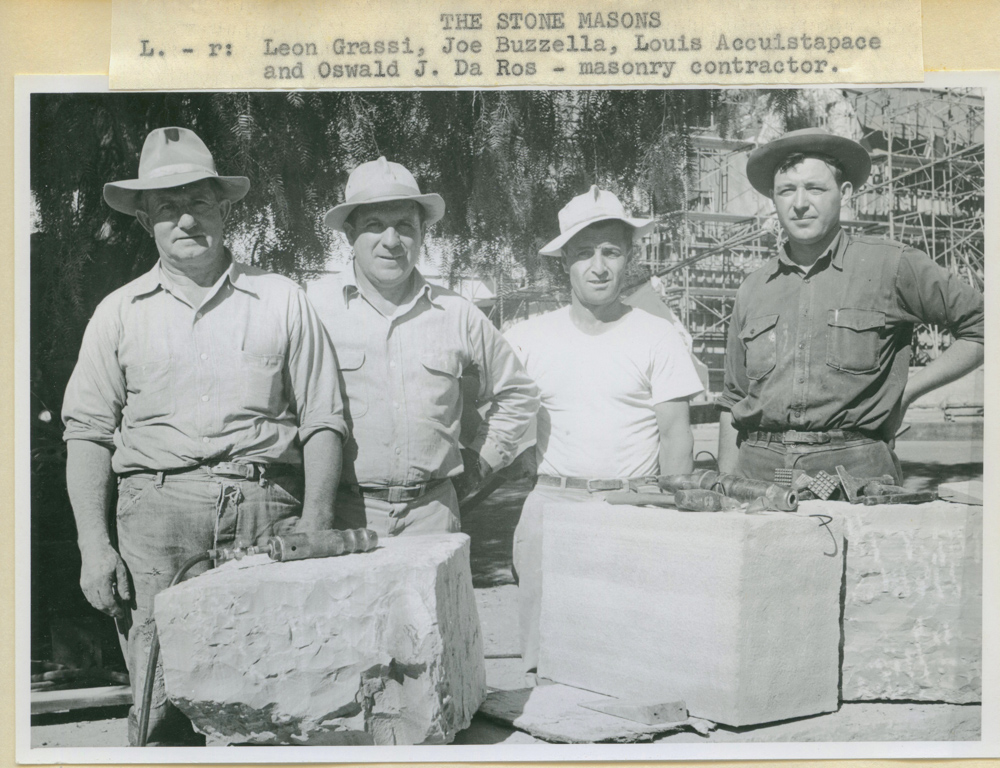

The entire front of the mission was removed in the 1952 restoration with Ozzie supervising the masonry team — which included Joe Buzzella, one of the original masons from the 1925 repair. (Interestingly, Ozzie discovered during this demolition that the entire tower structure was a facade.) The mission was repaired and restored and strengthened, all without altering its historic integrity.

Forty years later, Ozzie was asked to come back, working to prevent the cemetery walls of the Old Mission — which were leaning more than six inches out of alignment — from collapsing.

But it was Ozzie’s integrity and work ethic that was to leave its lasting mark. Mason Richard Cutner summed it up, “What Ozzie did for this community was to establish a standard by which everyone built. It did not matter if you were not in Ozzie’s trade. Whether you were a plumber, finish carpenter, mason, electrician, brick layer, or whatever. He demanded the plumb-square-level from everyone. Every trade had to attain to it. The idea was you never did a half-ass job. Even if no one would see it: Before you buried it, you had to make sure your work was ‘plumb-square-level.’”

Another young contractor noted, “If you were on a building project, word would spread when Ozzie was visiting onsite. Without being told, everyone knew that they had to up their standard. The whole atmosphere changed. Everyone wanted their work to be perfect.”

Gail Young (of Young Construction) remembered, “Even up to his last, Ozzie always had his edge and his playfulness; he never lost it. But Ozzie was a legend who has enhanced and beautified so much of Santa Barbara.”

Ozzie was also a man of unabashed faith. I remember he once publicly expressed his strong opinion on some issue of moral concern. Speaking with him later about being perceived as politically incorrect, he turned to me and said, “Erin, one day I am going to meet my Maker — and I will have to answer to Him.”

He kindly supported the Monastery of Poor Clares, Catholic Charities, Our Lady of Sorrows, the Old Mission, Villa Majella, Notre Dame School, Knights of Columbus, Sisters of Notre Dame, and in 2005 received a papal honor — the Pro Ecclesia Et Pontifice award in recognition of his commitment to the ecclesial community.

Ozzie was a below-the-radar philanthropist, not only giving brickloads of his time to organizations, both as a contractor or as a boardmember, but also contributing plenty of his coin to help. Just some of the organizations Ozzie supported: Visiting Nurses Association, Cottage Hospital, Arts Fund, CAMA (Community Arts Music Association), the Museum of Art, Met Opera, Lobero Theatre, CASA (Court Appointed Special Advocates), Girl Scouts, Transition House, Girls Inc., Boys & Girls Club, Marymount School, and the Scholarship Foundation of Santa Barbara.

The 2011 John Pitman Award for Lifetime Achievement in Historic Preservation was presented to Ozzie for his exemplary professional dedication in the preservation of historic architecture and environment, noting his work with the Architectural Foundation, Santa Barbara Historical Society, Trust for Historic Preservation, Museum of Natural History, Lotusland, UC Botanical Garden, Santa Cruz Island Foundation, Land Trust for Santa Barbara, Mono Lake, and Elings Park.

Ozzie Da Ros’s professional achievements, dedication to quality craft, and, yes, integrity will continue to be seen and felt throughout this community for generations. The name Da Ros continues to be synonymous with stonework in Santa Barbara, as two of Ozzie’s three children continue as the third generation to run the family business at Santa Barbara Stone.