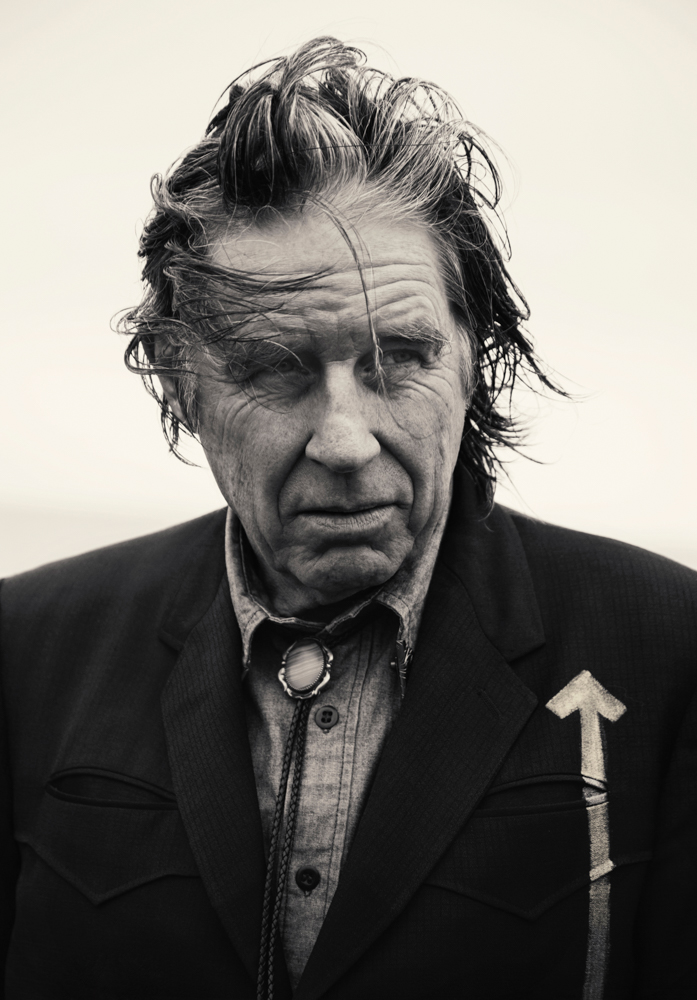

John Doe is many things: a founding member of X, one of Los Angeles’ best and brightest first-generation punk-rock bands, and The Knitters, a country-music offshoot. He is also a solo artist who has released eight albums as well as done several side projects with Jill Sobule and The Sadies. He has acted in more than 50 films and television productions; he’s a poet who has also taught workshops; and he’s the coauthor, with Tom DeSavia, of Under the Big Black Sun: A Personal History of L.A. Punk. I recently chatted with Doe over the phone in advance of his upcoming Lobero Theatre appearance as part of the John Doe Folk Trio.

Your latest solo album, The Westerner (2016), is a really strong record. I especially liked the songs “Alone in Arizona,” “Sweet Reward,” “The Other Shoe,” and “Rising Sun” in terms of beautiful song craft. Tell me about making this album. Well, it’s dedicated to a friend of mine, Michael Blake, who wrote Dances with Wolves. He passed away, actually, right as we started making the record. I wrote a bunch of the songs about him — or kind of fictionalized the events of his life. He lived in Arizona … He was all about the desert. Maybe seven or eight years ago, Howe Gelb [from the band Giant Sand] and I got to be closer. He’s been instrumental in a sound that’s been coming out of Tucson for a while. If it wasn’t for him, Neko Case and Calexico would sound very different. He [Gelb, who coproduced The Westerner] pioneered that very spare and reverb-y sound that comes out of Tucson …. Desert music with psychedelia is Howe Gelb’s stock and trade. As far as the subject matter and the songs, I just like to paint a picture and tell a story as economically as possible — and this time I tried to cut away what wasn’t necessary musically.

Who were your musical influences, and how did you gravitate toward playing bass early on? Bass seemed like it was going to be easier. [Laughs.] It was only four strings. I listened to a lot of folk music when I was a kid and show tunes and music on the radio. But, yeah, I love the bass, and I wrote all the early X songs on bass. What I’m doing now tends to lend itself toward guitar and piano.

You have a rich, distinctive singing voice. Was that something that came naturally to you or did you have to work at it? I think a little bit of both. [Laughs.] Singing is mysterious …. There are some people who don’t have a traditionally “good” voice — such as Macy Gray, she has kind of an odd voice — but she communicates … and so does Edith Piaf or Bob Dylan or people like that. I have more of a smoother, not terribly characteristic [style] — not like those people I just mentioned. I’ve got to be careful to have a little bit of range, arrangement, or different kind of songwriting so it doesn’t get dull. That’s why I made that record with The Sadies called Country Club. The Sadies are a great band … they’re wonderful, and they get the left turn all the time. So that seemed a natural combination. But did I develop it? Sure. At first I tried to sing a little bit flatter, not sing as much as a crooner — which I can — because of the punk-rock style. And I still like that, but on solo records, I’m able to do more of a classic singer [style].

Who are some singers you admire or who influenced you? Lead Belly. Mary Martin, the Broadway singer. More recently, I would say Elliott Smith or Merle Haggard.

In 2016, you wrote Under the Big Black Sun, a memoir chronicling the early L.A. punk-rock scene. How did that come about? Was it easy or challenging to get Exene Cervenka, Henry Rollins, Jane Wiedlin, Mike Watt, Dave Alvin, and other key figures of the ’77-’82 SoCal punk era to contribute their vibrant first person accounts? L.A. punk rock has always been the redheaded stepchild compared to London and New York, so to have a real publisher, a real opportunity to tell the story — everybody was ready, willing, and able. The best idea I had about the whole thing was to be the narrator … write about X … and then get everyone else to tell their truths. Everybody had a topic. [The Go-Go’s guitarist/singer/songwriter] Jane Wiedlin’s topic was the Canterbury apartments [a 1920s apartment building in Hollywood close to punk club the Masque], because that’s where we all collected and exchanged ideas — that was our salon. We weren’t Ernest Hemingway or Gertrude Stein, but that’s what we needed.

You did live your own punk-bohemian version of Hemingway’s memoir, A Moveable Feast. In a way. Dave Alvin’s topic was how his band [The Blasters] and his music got pulled into the punk rock scene. Henry Rollins’s topic was what it was like to come from a fairly small [Washington,] D.C., scene into a bigger, meaner L.A. punk-rock scene in the eye of the Black Flag hurricane. Xene’s topic was the social revolution that we were a part of. There’s going to be a sequel memoir, Wild Gift, which will have stories from people from different disciplines — Allison Anders, who is a filmmaker; Tony Hawk, the skater; Shepard Fairey, the artist; Tim Robbins, the actor — who were all involved in the L.A. punk scene.

Last year marked the 40th anniversary of your band, X. Can you speak to X’s legacy both to the punk scene and to American music? [Laughs.] I think everyone’s grateful that we’re on tour right now. It’s not as if we had 40 years and said, “Okay, good enough. See ya later!” I think it’s been an emotional and grateful time. Forty years with the same people and connecting to an audience that was so seminal … 15 or 20 years ago, we might not have given it as much respect … but now we realize that’s an accomplishment, and that’s pretty good! The fact that we’re getting paid pretty well and that there are also young people that show up in the audience … that means something, and we recognize that.

Are there any plans afoot for you, Xene, Billy Zoom, and D.J. Bonebrake to record a new X album? We’ve talked about it over the years … we’ve just released a live record that we did in South America. We’re going to try to do it in November — I don’t know if that’s what we’ll actually do, but we’re going to try to figure that out.

When composing the lyrics to your X songs, were you and Exene influenced by writers like Charles Bukowski, John Fante, or Raymond Carver? Absolutely. I went to school for writing and poetry in Antioch and Baltimore. Exene is much more of a natural. We just made a silent promise to each other that we were going to tell the truth — and we did.

Those old X songs stand the test of time! Thank you. I appreciate you saying that. I think if you have a good song, you can do it many, many different ways.

There’s so many great X songs I’d love to know the story behind … but I’ll limit it to three. What can you tell me about “Blue Spark”? “Blue Spark” was written when I was starting to be Xene’s boyfriend, and I lived by the Santa Monica Pier, which had a bumper car — [which] is attached to that metal screen on the top — and there would be a blue electrical charge, and that’s the blue spark.

What about another top X song, “Poor Girl”? That’s more just a story … drawing from some places that I used to hang out in Baltimore. [Laughs.] Unknowingly, I think I wrote it about someone who was manic depressive … Almost who shuts off the world. But it was just a story; it wasn’t about a particular incident.

Sometimes you paint your own image in your mind when you hear the lyrics to a song … for some reason when I hear “Back 2 the Base,” I always picture Montgomery Clift in the film From Here to Eternity trying to get back to the base at Pearl Harbor. Well, I love that movie. He was such a burner in that movie … he just burns up the whole screen. And Ernest Borgnine, too. [“Back 2 the Base”] was something that happened to me while on the RTD bus in L.A. There was someone who had lost their mind …

As they tend to do in L.A. … Well, they do it everywhere [Laughs.] … but he was screaming about [unsavory acts between] Elvis and dogs … and all I had to do was just write it down. And he said: “I am the king of rock ’n’ roll,” and he had a picture of Stevie Wonder on a magazine, and he was holding that up and yelling at people. Finally, they pulled the bus over, and a police helicopter was circling, and the cops came and took him away. And he also was yelling: “You’ve gotta get me back to the base!” or “I’ve got men at the base waiting for me — get me back to the base!’“ All I had to do was just try not to get beat up and write it down. [Laughs.]

Was it a fairly organic progression for you as a solo artist to go from punk to American roots and folk music? Yeah. I think there’s so many similarities between the economy, telling a story, and the political side to both. And I think when you do solo stuff you allow yourself to be a little more personal because you’re not speaking for a group …. The most difficult part was finding a voice that’s really true. I don’t think I got there until my fourth or fifth record — the one called Forever Hasn’t Happened Yet. From there, there have been three or four records that have all been similar. But it’s hard. When you work in a band, you’ve got a lot of other people to help form that sound.

Who are the other members of the John Doe Folk Trio, and what will you be playing at your upcoming Lobero Theatre concert? On upright bass is David J. Carpenter. I’ve played with Dave for many years; he’s been on at least five records that I’ve made. He currently tours with Roger Hodgson from Supertramp. He also played on that Dead Rock West record that I produced a couple of years ago. He’s just a very musical stand-up bass player and a stand-up guy. And Stuart Johnson, he plays drums, and he’s also been on several records, and we’ve done a number of tours together …. Stuart approaches the drums very musically and adds a lot of character to it. And I wanted to strip it down, and I’m basically doing folksier versions of songs that I’ve done over the years, and add a Carter Family song called “Hello, Stranger,” and I may do a version of “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” and four or five X songs like “The New World” and “The Have Nots” and things like that.

411

The John Doe Folk Trio plays Sunday, September 16, 7:30 p.m. at the Lobero Theatre (33 E. Canon Perdido St.). Call (805) 963-0761 or see lobero.org