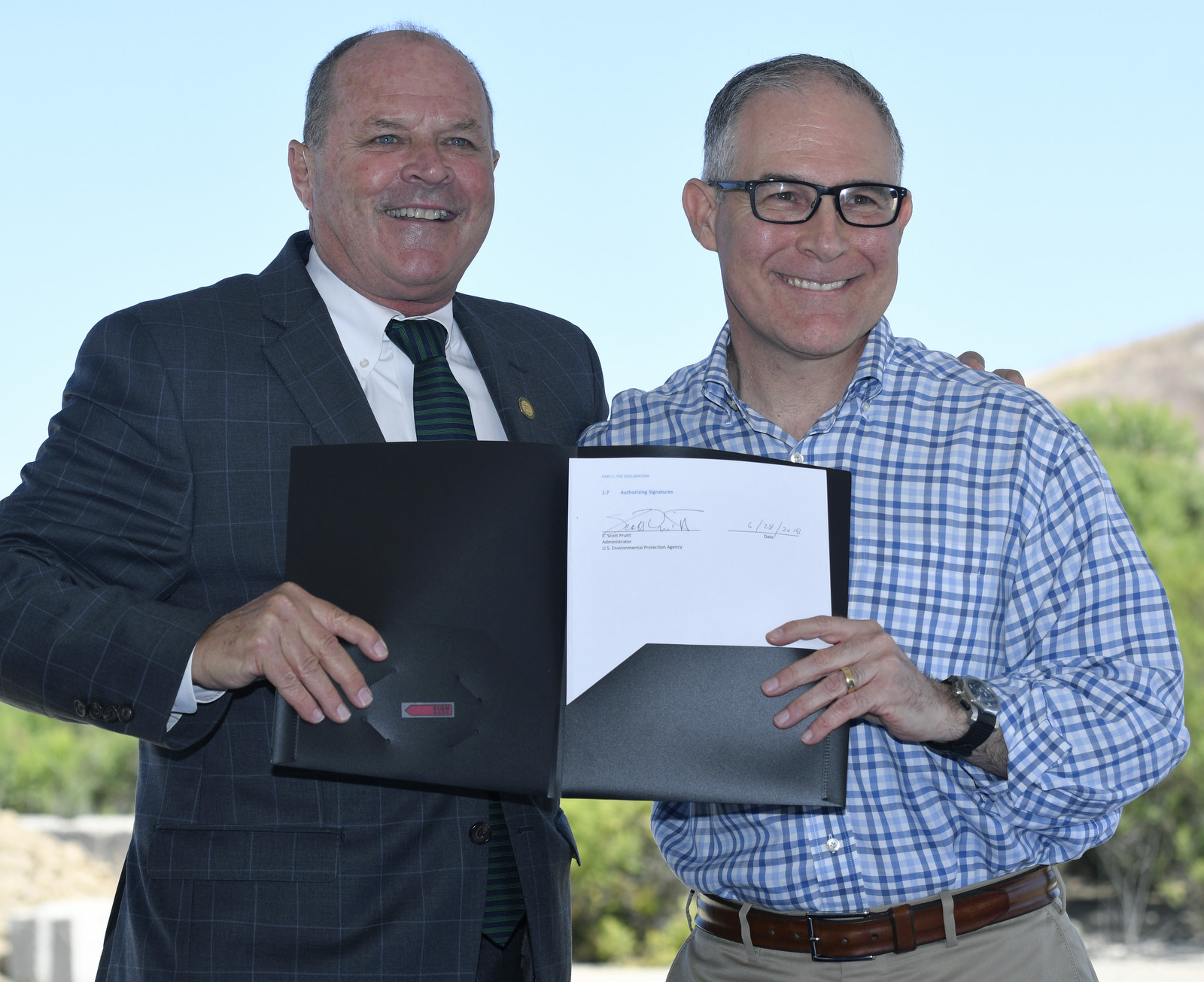

It was just one week and a day ago that former Environmental Protection Agency czar Scott Pruitt and EPA Pacific Southwest regional director Mike Stoker were mugging for the cameras at Santa Barbara County’s only toxic waste Superfund site, located 15 minutes outside of Santa Maria in the Casmalia Hills. Pruitt and Stoker were there to sign a critical but esoteric legal document signifying adoption of a final cleanup plan for what ranks as one of the worst toxic messes — encompassing 5.6 billion pounds of toxic chemicals spread out over a 252-acre site — in the country. Given that the toxic dump in Casmalia was shut down in 1989 — after a 17-year run — it was about time.

But in the eight days since, a whole lot’s happened. Most notably, Pruitt resigned as head of the EPA, concluding a short but exceedingly tumultuous reign defined by an in-your-face antagonism to anything resembling an environmental agenda, coupled with a nonstop stream of alleged ethical violations, each one seemingly more petty and venal than the next.

When asked what difference Pruitt’s departure meant for District 9 — the southwestern coastal region of the EPA, Stoker — a former Santa Barbara County supervisor and longtime player in local and statewide Republican Party circles — was emphatic. “Nothing,” he stated. “For District 9, it’s business as usual. It’s going to be the same on Friday and it will be the same on Monday, with or without Administrator Pruitt.”

Stoker has been effusive with his praise of Pruitt in the past and remained complimentary of Pruitt’s professionalism and that of Region 9’s headquarters in San Francisco. Stoker stressed he was not setting national policy, just implementing it. He said he heard about Pruitt’s decision to resign via email from an unnamed high ranking member of the administration.

“I’ve been around politics long enough that nothing is a surprise,” Stoker said of the resignation. “I don’t know if I’d call it crazy,” he said, “but definitely a little bit different.”

Stoker declined to speculate as to the timing of Pruitt’s announcement. He’d been under such intense fire for so long that even many prominent Republicans — like his political mentor Oklahoma Senator James Inhofe, also an ardent climate-change denier — suggested it might be time for Pruitt to step down. Although Inhofe would reverse himself, the damage was done. Conservative columnist Laura Ingraham wrote Pruitt had come to embody the swamp that needed draining in Washington and likewise called for his resignation.

Stoker acknowledged he himself might not have done some of things Pruitt was accused of doing — he provided no examples — but insisted Pruitt’s opponents had been out to get him well before any allegations of ethical improprieties had surfaced. Stoker blamed the escalating culture of polarization that’s seized politics in Washington, D.C. “It’s just another chapter illustrating why good people don’t want to serve,” he said.

Stoker said that Pruitt — a political lightning rod because of his outspoken insistence that climate change isn’t real and carbon dioxide is not a contributor — is frequently targeted by critics for public displays of opprobrium. He cited the well-publicized confrontation by Pruitt at a restaurant in San Francisco in which a woman accompanied by her child told Pruitt he should resign on his own before he was forced out. “I heard from Adminstrator Pruitt’s security team that incidents like that happened all the time,” Stoker said.

Stoker shrugged off the suggestion that Pruitt may have brought some of the trouble upon himself by the extremity of his positions — under his administration, the words “climate change” all but disappeared from EPA websites — and his reluctance to meet with environmental organizations. In his first year, only one percent of Pruitt’s meetings were with environmental representatives. By contrast, 25 percent involved representatives from regulated industries.

Stoker has expressed a willingness to meet with environmental organizations his San Francisco headquarters. “I’ve been able to walk down Cabrillo Boulevard on the Fourth of July and run into my environmental friends here and say hello,” Stoker said. “We don’t agree on everything. Or even on a lot of things. But we manage to keep it civil.”

Pruitt’s pugnacity has hardly been reserved for the environmental opposition. In recent months, Pruitt famously lobbied President Donald Trump to fire Attorney General Jeff Sessions — with whom Trump was furious at the time for allowing the appointment of special prosecutor Robert Muller — and to give him the job. Even within the Trump administration, where politics is engaged with the reckless abandon of a demolition derby, Pruitt’s lobbying seemed excessive. And even within a White House seemingly impervious to controversy and criticism, the 13 ethics investigations targeting Pruitt seemed like a lot. While some of those were triggered by Freedom of Information Act filings submitted by the Sierra Club — such as reports that Pruitt instructed an aide to find his wife a job with a political advocacy organization paying $200,000 a year — the most leaks came from other White House sources. Former Trump aide Rob Porter has been identified as the source of many retaliatory leaks that have been sprung against Pruitt. Porter was forced to resign earlier this year after he was outed for having physically assaulted his two wives. The outing was done by a former romantic partner who worked in a high level administrative position at the EPA.

Stoker was likewise leery about commenting about Pruitt’s interim successor Andrew Wheeler, a former lobbyist for the coal industry and also a political protégé of Oklahoma Senator Inhofe. As for Pruitt, Stoker speculated he’s probably relieved. “He certainly wasn’t doing this for the money.”

Stoker noted that last week’s Casmalia event inoculated Pruitt from potential protests given its remote location, high fence, and security.

Stoker was first appointed to the Santa Barbara County Board of Supervisors in the 1980s and then twice ran for office in the 1990s, when he helped orchestrate a conservative takeover of the board. Stoker has highlighted his role in making the motion for a board resolution to have the Casmalia toxic dump declared a Superfund site. (Some of the town activists who led the charge against the dump — like former elementary school principal Ken McCalip — said Stoker’s motion was strictly ceremonial. “By the time he was around, all the real work had already been done,” McCalip said. Casmalia residents, including McCalip, won a $10 million class-action suit against the operator of the site.) By that time, the groundwater basin — believed to be all but impermeable — had been so contaminated with cancer-causing chemicals that even with aggressive pumping for several thousand years, EPA technocrats say, it can never be remediated. At one time there were 43 storage and evaporation ponds, many of which sought to “evaporate” the contents by funneling them into the air via a streaming fountain.