Evacuation as a New Way of Life in Santa Barbara County

When Do Officials Pull the Trigger?

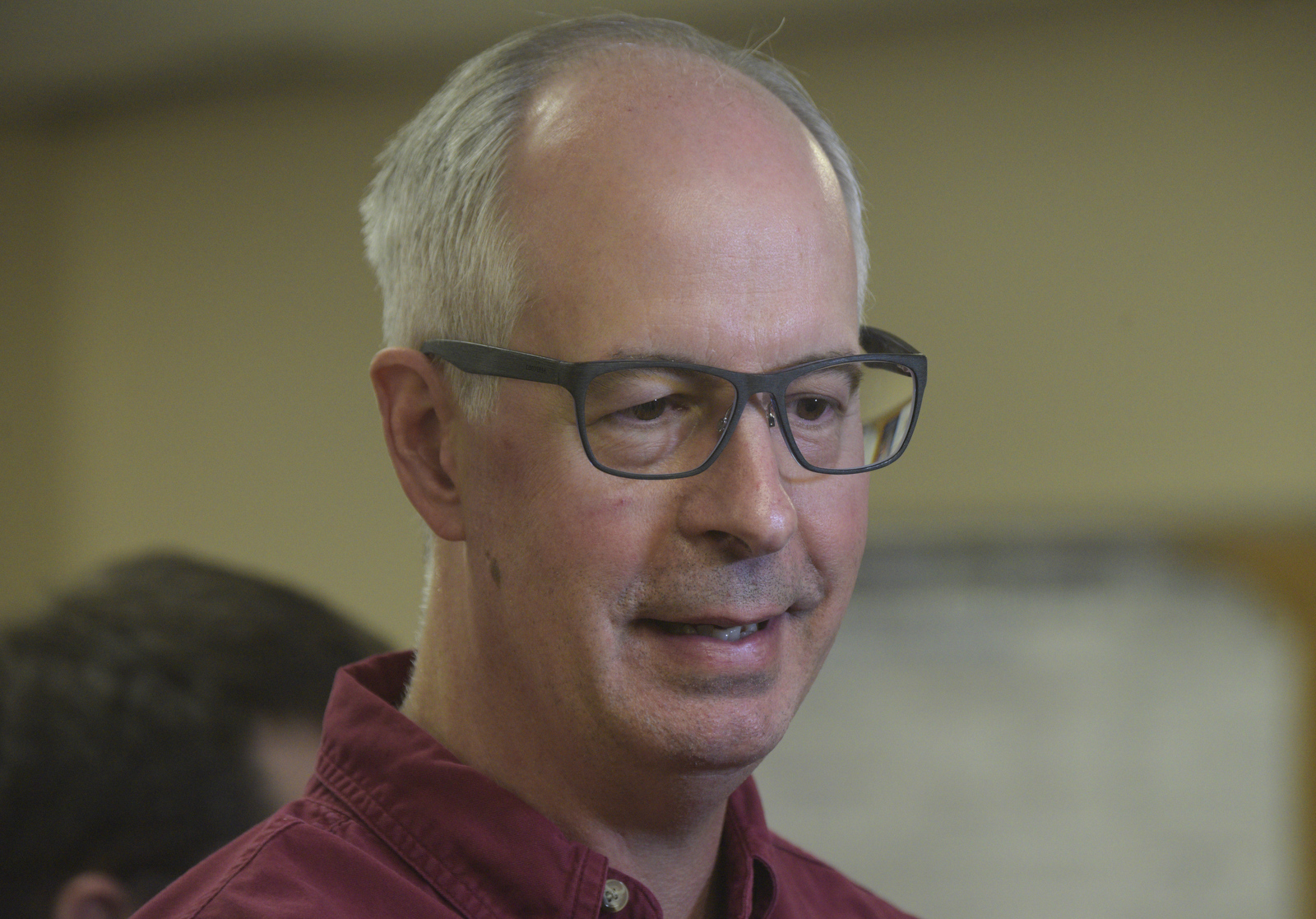

The phrase “the new normal” has been so overused in the past 10 years it’s almost become a form of linguistic abuse. There are certain situations, however, where the phrase fits the bill. Three evacuations within a three-month period seems to be one of them. Since the Thomas Fire broke out on December 4, Santa Barbara County Sheriff Bill Brown has emerged as the South Coast’s de facto Evacuator-in-Chief. Since his first election in 2006, Brown has presided over more evacuations now than he can remember or count. Little wonder that he’s inclined to pepper his remarks in press conferences with references to “the new normal.”

At a press conference this Wednesday about whether mandatory evacuations would soon be ordered in anticipation of Thursday night’s rainstorm — they were — Brown suggested that evacuations might have just become a routine fact of life along the South Coast for the next two to five years. That, he philosophized, might be the price of living in a place “so beautiful.”

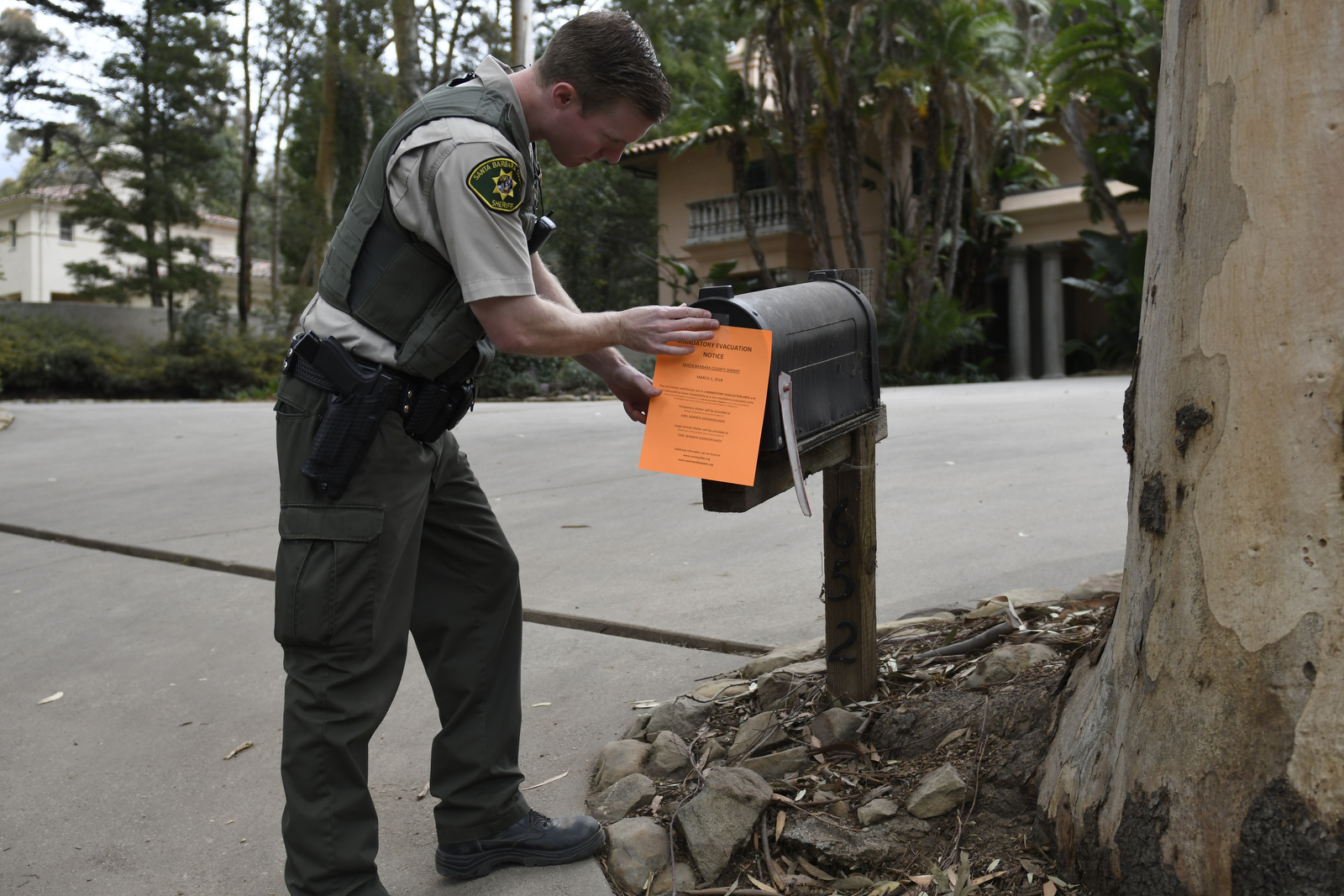

Beauty may lie in the eye of the beholder; debris flows are inclined to hit you right between the eyes, assuming you sit still long enough to behold them. Evacuations for the January 9 flood and debris flows — which killed 23 — adhered to plans concocted in 2009 in response to the Jesusita Fire. Those plans focused on the demarcation line of State Route 192. Debris flows follow drainage channels and creeks, not street grids. Brown has since tossed out that playbook and adopted a new creek-based evacuation plan.

The $64 million question, of course, is when to pull the trigger and order a mass evacuation. Anytime it rains?

The short answer is we don’t know. The long answer is the same.

In the wake of the Thomas Fire, the very soil of Santa Barbara’s scenic front country has become an explosive force of nature, ready to uproot itself and come careening down the slopes in the form of a concrete-like slurry, carrying millions of cubic yards of mud, trees, brush, rocks, and giant boulders at speeds exceeding 30 miles an hour. After such a scorching, it typically takes the soil two-to-five years to restore itself to some semblance of stability. In the meantime, the $64 billion question remains how much rain can the slopes absorb before they pose a serious threat?

The real question, it turns out, is not how much, but how hard.

The magic number meteorologists and geologists agreed upon for this Thursday’s storm — predicted to drop one to three inches — was half-an-inch an hour. Anything that intense — or more — could trigger a debris flow. Early Wednesday, the weather forecasters were predicting as much as two-thirds of an inch an hour during peak hours. But later in the day, it appeared the storm was slowing down. The peak rains would arrive not at 9 p.m., as initially projected, but at midnight. That time has now been pushed back a couple hours further. It also seemed like the storm would not be packing quite as big a punch.

Eric Boldt, a warning coordination meteorologist for the National Weather Service (NWS), said the bulk of the storm would peak at one-third of an inch to four-tenths of an inch an hour. But it had the potential, he said, to hit the half-an-inch trigger point. Between Wednesday night and Thursday morning, the NWS would provide two additional weather reports to a small flotilla of emergency response planners led by Brown and Rob Lewin, Santa Barbara County’s emergency response czar. Their hope was that by Thursday morning the storm would show further signs of slowing down and diminishing in capacity. It didn’t. In fact, the storm was pegged dropping six-tenths of an inch in an hour as it went through Monterey.

Boldt, a tall lanky guy given to baseball metaphors, stressed that the approaching storm is “a minor league storm” and very much not a major league storm like the one that hit Montecito on January 9. “But we have to be careful. Even minor league players can hit it out of the park.”

Boldt stressed that the approaching storm was not a thunder storm, meaning it won’t ride nearly as high in the sky and won’t carry as much water. The peak dump inflicted by this storm, he said, would pack one-third the violence and volume of the January deluge. Unlike the January storm — which was all but aimed directly at Montecito — the approaching storm is moving down the coast in a sweeping motion, meaning a far greater swath of land will be affected. That means there’s greater avenue for potential debris flows.

All these are considerations to be weighed in the “if and when” to pull the evacuation trigger. And as scientific as it sounds, it’s still very much an evolving art. Brown acknowledged as much. “We just don’t what’s going to happen,” he said. “This is the first significant storm right after the big one. We don’t know how the watershed will respond to it.”

That this was the first storm after, Brown acknowledged, weighed heavily in the decision.

Right now, the creeks and debris basins are 92 percent clear from the vast volumes of rubble and stone and debris. That number is somewhat misleading. All but one of 10 creeks are totally clear. All but one of five debris basins are too. The one holdout, located in Carpinteria’s Santa Monica Creek, is by far the biggest in the county. It was filled to the brim in the wake of the January 9 debris flow, choked with thousands of uprooted trees. That’s now 50 percent full. Or as Tom Fayram, county flood control chief might put it, 50 percent empty. “If you pinned me up against the wall and made me answer, I hate to say it, but I think we’ve got the creeks and basins in pretty good shape,” he said.

Fayram is the first to admit that the carrying capacity of all those creeks and basins are no match against a massive debris flow sparked by a 200-year flood event. What’s approaching Santa Barbara is no 200-year flood. But still, no one is in the mood to take any chances, particularly after January’s death toll. Brown met with a room full of emergency planners two times Thursday morning. There was a vigorous discussion, he said, a candid exchange of views. Challenging questions were asked. But in the end, he said, the conclusion was unanimously in favor of mandatory evacuation.

Brown is well aware of what a burden and hardship evacuations can be. Perhaps in this instance, the third time will prove to be the charm. But Brown worries about being the boy who cried wolf. What happens if nothing happens and people have been forced to move? Aside from the obvious inconvenience involved, there’s the more serious matter of credibility. Perhaps future evacuations can be calibrated with more surgical precision, minimizing the number of people displaced. Obviously, people living near creek channels are in far greater danger than those living further away. No attempt at that level of granularity was attempted this time. Debris flows are famous for jumping the confines of existing creek channels and creating brand new pathways to the ocean. Brown estimates 22,000 residents will be asked to uproot themselves — for up to two weeks in a worst case scenario — and another 8,000 workers and shoppers moved out of the area.

County Supervisor Das Williams, who lives in a high danger flood zone in Carpinteria, stated, “It is not our job to gamble with people’s lives. It’s our job to give people the best information we can.” Trouble is, sometimes the best information isn’t good enough. And as long as the hillsides can turn explosive when mixed with rainfall, Bill Brown and people like him will be forced to choose between imperfectly calculated risks. And what’s that, if not gambling.