Eddie Hsueh: Santa Barbara’s Great Peace Officer

Bringing Safer Ways for Law Enforcement to Work with People with Mental Illness

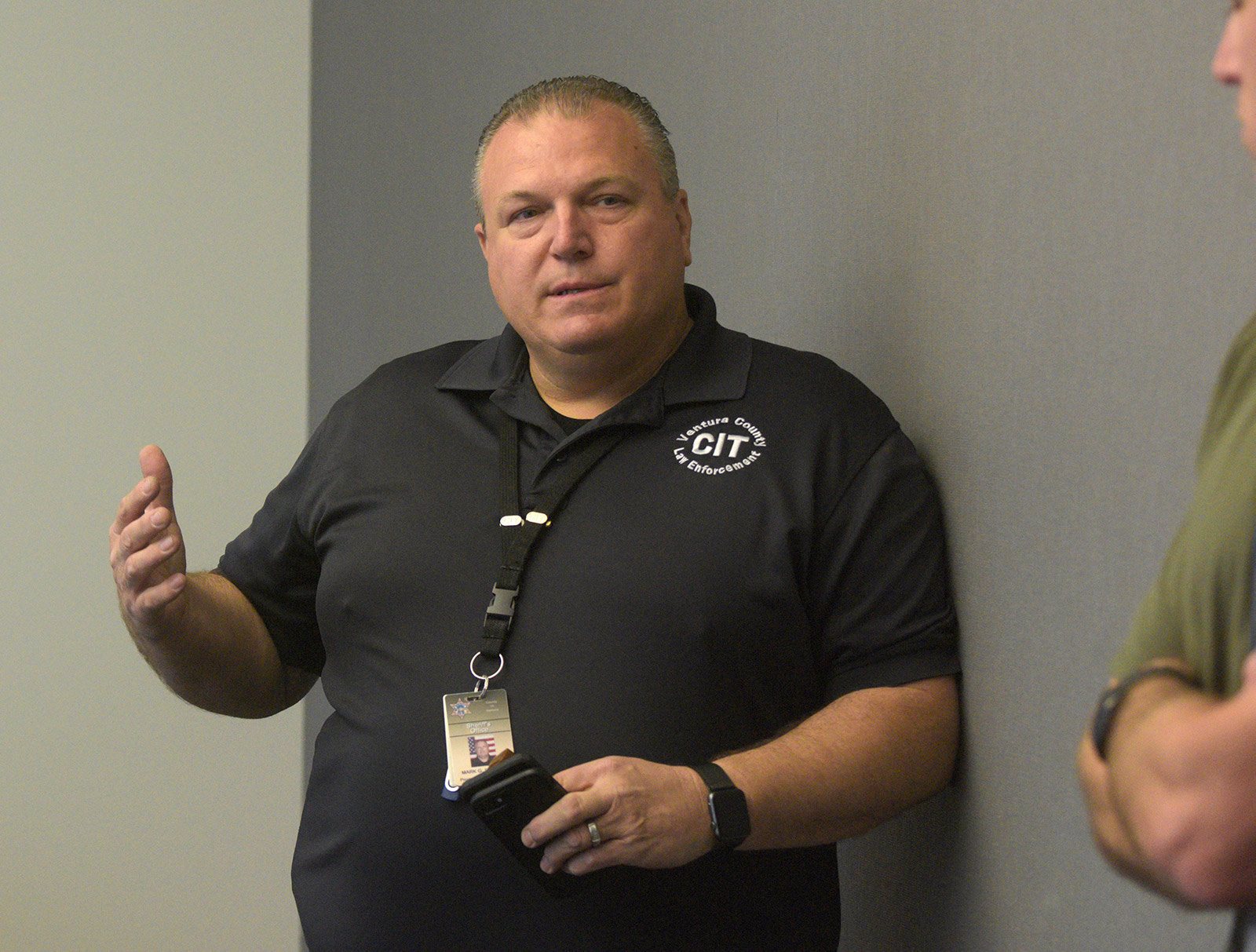

The first thing you notice about Eddie Hsueh is his size: not huge but somewhere between a Coke machine and a refrigerator. Back in the day, Hsueh was a seriously competitive weight lifter. He could bench-press 578 pounds and deadlift 661. It’s been a while. But it still shows.

The second thing is his total lack of cop vibe. He gives off no whiff of the command-and-control psychic armor cultivated by many in law enforcement as a form of self-defense and intimidation. Instead Hsueh — pronounced “shway” — speaks softly. He smiles a lot.

For the past 31 years, Hsueh has carried a gun for the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office. For 26 of those, Hsueh worked patrol. Now he’s a lieutenant. As of January, Hsueh became de facto chief of police for the cities of Solvang and Buellton, both of which contract with the Sheriff’s Office for services. It would seem a plum assignment for someone fast approaching retirement, but Hsueh isn’t trying to slow down. He has much bigger fish to fry.

For the past three years, Hsueh has led a lonely uphill charge within the Sheriff’s Office to change the way deputies interact with people with mental illness. It starts with training. It’s about minimizing confrontations and gaining more time to find nonlethal solutions. Fewer officers get hurt. Fewer people get shot. Nationwide, half of all fatal police shootings involve people with mental illness.

Hsueh has made sure everyone in his department — whether they carry a gun or not — has a minimum of eight hours of training. But that’s just a start. Hsueh recently developed a state-approved 40-hour training curriculum and has spearheaded the department’s Behavioral Sciences Unit, which tracks and details all deputy interactions with people with mental illness. This information is shared with the Department of Behavioral Wellness. Amazingly, Hsueh made all this happen in a cash-strapped, top-down, chain-of-command bureaucracy without any funding.

In the wake of Florida’s mass school shooting, the deficiencies of America’s mental-health system are once again under the microscope. President Donald Trump, loath to entertain restrictions on the sale of guns or ammo, is once again blaming people with mental illness.

As Hsueh can attest, it’s not quite that simple.

Yes, he can rattle off the names, dates, and body counts of all the psychologically unhinged who went on killing sprees in Santa Barbara County during the past 20 years. He personally responded to some. In the wake of Elliot Rodger’s deadly 2014 Isla Vista rampage, California passed laws giving police agencies greater authority to confiscate weapons from the psychologically unstable. Hsueh takes pride in the fact Santa Barbara County leads the state in such confiscations. But the vast majority of people with mental illness, Hsueh insisted, are not dangerous. For 99 percent, he said, the only danger they pose is to themselves.

With two years left before his retirement, Hsueh is not only trying to put his current mental-health initiatives on solid financial footing but also trying to fund a program where mental-health workers accompany deputies on patrols. He has a long way to go on both. What little funding the program has runs out in March.

It will be a lot harder to find the time for these projects at his new assignment, where he will have to work with two city councils and two city managers, but, he said, they have the same problems in Solvang and Buellton as they do everywhere else: “I just know we can do a better job.”

Origin Story

As a kid, Eddie Hsueh was a certified Batman freak. His office is decorated with Batman drawings and figurines. He said he learned to read by devouring old Batman comics. “It’s why I became a cop,” he explained. “I wanted to fight crime, protect people, and put the bad guys in jail.”

When Hsueh was 17 years old, he was standing in a Santa Maria mall parking lot when a homeless person rattled by with a shopping cart. “I was afraid I’d wind up like that,” he said. But then, a cop car drove by and Hsueh had his Batman revelation. He signed up to be a reserve officer with the Sheriff’s Office. Since then, he’s worked under five sheriffs.

Things could have worked out very differently.

“I didn’t grow up a person of privilege,” Hsueh said. Indeed, he didn’t. He was born in East Los Angeles and never knew his biological father growing up. His extended family moved around the state, managing sleazy motels. When he was 12, they moved to Santa Maria.

As a child, Hsueh was given his grandfather’s name, Ellsworth H. Pond. In exchange, his grandfather, who was the head of the family, “borrowed” Hsueh’s Social Security number. Hsueh found out many years later when he had to clean up his credit history. The record had shown that “by the time I was 11, I was already bankrupt,” he said, laughing.

His mother had an even tougher life. At age 9, she was “given” to the Ponds by her natural mother, who had decided to move on. The Ponds kept her out of school, made her believe she was developmentally disabled, and told her to say she was brain damaged. “She wasn’t retarded,” Hsueh said, “But that’s how she grew up.”

Police were frequent visitors to the motels his grandfather managed. Hsueh remembered that once, when they were called to a murder, an officer let him sit on his motorcycle. “He seemed eight feet tall,” Hsueh recalled.

After four years in Santa Maria, the Pond clan moved on, but Eddie, who never called himself Ellsworth, stayed put. At 16, he dropped out of school and took on three jobs: working in restaurant kitchens, cleaning up around construction sites, and scrubbing telephone booths from Ventura to San Luis Obispo, for which he earned a buck a booth. He got into judo, studying with Sensei Isamu Yamamoto, who ran a Japanese cultural club and dojo in Santa Maria. He lifted weights, ran, and trained in other, flashier martial arts. “It kept me out of trouble,” he said.

When he joined the force 31 years ago, Eddie Pond, as he was then known, started off working patrol in Santa Maria. Mike Durant, who just retired from the Sheriff’s Office, worked with him. “He was huge. Solid as a rock. A great beat cop,” Durant recalled. “He was very soft-spoken. Me, I used foul language all the time. Eddie? I don’t think I ever heard him use it.”

David Saunders, who teaches law and criminal justice at Santa Barbara City College, also remembered Eddie Pond from his own days as an S.B. County Sheriff’s deputy. “He was a gentle giant,” said Saunders. “Deputies have a whole lot of discretion in the use of force. He was always on the lighter side. He was not a meathead.”

Force, however, is part of the job. “It’s never pretty,” said Hsueh. “Nobody wants to see it.” Hsueh remembers getting into it with a Korean War vet with Alzheimer’s. The man held a knife to his wife’s throat. As Hsueh and his partner tried to talk him down, the man threw the knife at Hsueh’s partner. It struck his partner’s leg, but with the handle, not the blade. “We could have shot him,” Hsueh said. “It would have been justified.” Instead, Hsueh tackled the man.

At age 40, after some old-time sleuthing, Eddie Pond met his biological father for the first time. He discovered that his father, whose last name was Hsueh, was born in China and, though extremely intelligent, had his demons. By the time they met, his father was a Pentecostal minister, but before that, he’d been living in his car for a couple of years. He also discovered a family he’d never known. Several aunts and uncles were exceptionally accomplished in their fields. It was inspiring. He became Eddie Hsueh.

It also opened his heart. “We deal with the mentally ill so much,” he said. “They’re a huge part of our caseload. And they’re so time-consuming. I always knew there had to be a better way of doing things.”

“When I was in the academy, we were taught you’d ask someone to do something, then you’d tell them to, and then you’d make them,” he recounted. “Ask, tell, make — that was our mantra.” That approach rarely works when confronting someone in a mental-health crisis. In fact, it often makes things worse. “As a general rule, people experiencing a psychotic break don’t hear too well,” Hsueh said with a soft chuckle. “So they’re not real good at following commands.” A better approach, he said, is to slow things down — to “de-escalate.”

Batman, Meet Robin

To the extent Hsueh has become his own Batman, Dr. Cherylynn Lee became his Robin. Without Lee, who runs the Behavioral Sciences Unit (BSU) that Hsueh launched, none of the crisis intervention training (CIT) could happen. Until a few years ago, Lee was running a methadone clinic in Santa Maria. But she was so taken with Hsueh’s vision that she agreed to work for free — though only for a while.

Lee has proved invaluable. Her mother was the first female psychologist ever to work for the Los Angeles Police Department, which might explain why Lee is so comfortable within cop culture. She gets it. It took time, but eventually Lee became accepted as part of the team. When deputies find themselves dealing with someone in psychological distress, they call Lee. Her cell phone explodes with such calls.

She dispenses real-time advice about who and what deputies are facing, warning about actions that might set off the suspect, recommending available services, and describing how to calm things down. If other agencies need to be called, Lee handles it. “I speak ‘clinician,’” Lee said. Deputies telling Behavioral Wellness caseworkers that their detainee was a “batshit crazy” person might not cut it.

Lee has successfully persuaded deputies to write detailed reports on encounters they have with people with mental illness. Lee then shares that information with Behavioral Wellness. More than 750 reports have been filed, three quarters of which are about individuals already known to Behavioral Wellness. One quarter, however, were unknown and were then contacted by Behavioral Wellness caseworkers. Some have since gotten treatment.

BSU includes 13 deputies who’ve undergone the 40-hour trainings and five others who consider the BSU work a compelling “collateral assignment.” (At the Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Office, very few assignments are full-time. Almost all deputies work multiple beats. Even those assigned to narcotics and gang details work collateral assignments.)

Jail Time As Treatment

In the past five years, the collision between people with mental illness and the criminal justice system has reached critical mass throughout the United States. Jails are expensive places to warehouse people with mental illness, and incarceration tends to trigger “decompensation” among the psychologically or chemically fragile. Though Sheriff’s Office officials insist no one is behind bars because of mental illness, the jail has become the county’s de facto mental-health treatment facility. Of the 1,051 inmates in county jail on October 20, 2017, more than half had been Behavioral Wellness clients at some point. (Behavioral Wellness only treats those clients with serious to acute problems.) There is an ongoing battle between the Sheriff’s Office and mental-health advocates over the adequacy of care at the county jail. In December 2017, Disability Rights California — an arm of the state — sued the county over treatment of their mentally ill inmates. That lawsuit is unresolved.

Only in the past year has the Sheriff’s Office started to track the use of force by county deputies, a policy instigated by Hsueh. Of the 142 use-of-force cases reported by the Sheriff’s Office in 2017, 68 — nearly half — involved persons “showing signs/behaviors consistent of mental illness at the time.” Those numbers, however, are not broken down to reflect severity of force involved.

At least one case ended in a fatality.

Funding a Crazy Idea

When Hsueh wanted to begin forming the BSU and CIT in 2015, he asked Undersheriff Bernard Melekian for his blessing and got it, though the undersheriff stressed there was no money in the budget for new programs. Melekian was well aware of the problem. He had testified before Congress in 2000 about it. “The number-one challenge facing law enforcement in the field is dealing with the mentally ill,” said Melekian in a recent interview. With the collapse of America’s mental-health system, cops have been forced to become “de facto social workers,” he said, but the only tools they have are their voices and their guns: “And then we wonder why things go badly.”

But despite the financial handicap, Hsueh somehow managed to keep the projects moving forward for three years. “It exists because of Eddie’s passion,” Melekian acknowledged, “and because he’s been creative enough to make it happen.”

How much longer Hsueh and Lee can continue, however, remains uncertain. The meager funding Hsueh found for Lee soon runs out. “I’m not sure where the funding’s going to come from,” he said.

The idea for the program is not brand-new. In fact, county mental-health workers used to train Sheriff’s Office deputies. It failed in part because the instructors lacked a law-enforcement presence. As a result, Hsueh said, “A lot of cops didn’t relate to it.” The idea for CIT specifically dates back to 1988, when the Memphis Police Department instituted a more effective training program. By 2001, the idea had reached Ventura County policing agencies.

Pioneering that effort on the Central Coast was Mark Stadler, a Ventura Police Department sergeant at the time who had originally joined the Santa Barbara Police Department in 1987. Five months into his job, Stadler and his partner were called to the Hotel Virginia (now the Holiday Inn Express on Haley Street), where a man wielding a machete had attacked the manager. The suspect was Robert Herbst, a transient from Wisconsin with burn scars over 80 percent of his body and a history of minor infractions. When Stadler’s partner sprayed Herbst with Mace, Herbst charged Stadler. “I started firing shots. I killed him that night.” Later, Stadler learned Herbst had mental-health issues. “What would I have done different?” Stadler asked. “I’d liked to have talked to him.”

After he transferred to the Ventura Police Department, Stadler was asked to look into CIT. Back then, it was an exotic idea. Lots of cops dismissed it as “soft,” he said. In June 2001, Stadler had an opportunity to use his CIT training. A jumper was on a Highway 101 overpass, but freeway noise made it impossible to communicate, so Stadler closed it down for two and a half hours, stranding 38,000 motorists, he said. At a nearby bar, patrons were yelling, “Jump!” from an outdoor patio. He shut that down, too. Stadler was talking to the jumper but getting nowhere. Finally, the jumper told Stadler to call the coroner; he was ready to leap. “I said, ‘You won’t need a coroner; it’s not that far down.’” That changed his mind.

Today, a consortium of six Ventura County law enforcement agencies and the mental-health department fund a CIT training program to the tune of nearly $300,000 a year.Stadler and another instructor train 100 sworn officers a year in a 40-hour program that requires 60 instructors, evaluators, and actors in role-playing exercises. “It’s the most impactful work I’ve done in my entire career,” Stadler said.

The key to CIT, Stadler said, is turning the volume down. First, assess the subject’s paranoia level; then position yourself accordingly. Don’t crowd, but remain close enough to respond. Speak softly, slowly. Listen. Use first names. Don’t bark orders. Soften the command voice. Don’t interrupt. Pay attention. The first priority, always, is officer safety. The second priority is time and space. Maintain enough space so there’s time to give less-lethal options a chance.

Stadler estimates 80 percent of all sworn officers in Ventura County have received this mandatory training. In Santa Barbara, only the eight-hour training is mandatory, but since the 40-hour training began in November 2017, 14 S.B. County Sheriff’s deputies have signed up for it.

In one four-day session, Hsueh and Lee brought in a combat veteran who talked about suicide, a person with schizophrenia who’d been arrested for stealing a car during a psychotic break, and a teen with autism who explained what triggered him: noisy radios, flashing lights, sudden motion, and physical contact, to name a few. Mental-health professionals also tried to explain the confounding maze of public and nonprofit agencies offering services.

Deputy Matt West of the Isla Vista Foot Patrol completed the 40-hour training. On duty he said he interacted with people with mental illness daily and that the system is frustrating and ineffective. He described a typical acute case: First, county mental-health workers have to be called since only they can assess the threat suspects pose to themselves or others and issue an involuntary psychiatric hold, known as a 5150. (Santa Barbara County is the only county in California in which officers cannot make the 5150 calls.) Typically, it takes over an hour for these caseworkers to arrive. By that time, the detained individual has often calmed down. As a result, the mental illness goes untreated, and the officers often find themselves responding multiple times to calls about the same individual. Aside from the exasperation and expense incurred by playing whack-a-mole with people with mental illness, there lies a troubling reality: Santa Barbara County doesn’t have enough beds — short-term or long-term — for those experiencing a psychiatric crisis.

Might Do Something Stupid

Nevertheless, West said the program was valuable, especially the role-playing simulation exercises. One involved someone diagnosed as bipolar inside a house and armed with a knife. Coincidentally or not, that scenario closely mirrored the fatal showdown between five S.B. County Sheriff’s Office deputies and 26-year-old Bryan Carreño on February 12, 2017, in a residential neighborhood off La Cumbre Road. Carreño had been diagnosed at age 16 with a bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Twice the year before the shooting, deputies had been called about Carreño. In both instances, he was alleged to have made suicidal threats. In one, his ex-girlfriend showed deputies the knife with which he tried to slash his wrists. In another, a county mental-health worker was called.

Carreño’s father — a retired custody deputy for the S.B. County Sheriff’s Office — had called on the night in question, describing his son as high on drugs, worried that he might “do something stupid” and that he might have a hatchet. Carreño had entered a neighbor’s home, extremely agitated, saying someone was trying to harm his father. Deputies located Carreño using a dog and helicopter. Two deputies entered the house as Carreño started to come out onto the backyard patio, carrying a knife. He told deputies to shoot him. The deputies, boxed in by the patio fence, opened fire, hitting Carreño 20 times. Two of the five deputies involved had responded to the previous calls for service involving Carreño last year. All five had received eight-hour CIT training. None had attended the 40-hour sessions.

District Attorney Joyce Dudley ruled the shooting justified, concluding the deputies feared for their own safety and the safety of fellow officers. The Carreño family has hired attorney William Schmidt, who has already filed a claim against the county. “They absolutely knew he had mental-health issues,” Schmidt said. “They had an obligation to try less lethal means. They had time to slow it down. They should have tased him or pepper sprayed him …. If that didn’t work, then they could have shot.” The county has denied the claim filed by Schmidt.

Details of the Carreño shooting notwithstanding, both Hsueh and Stadler stressed that people calling law enforcement to report a relative or friend experiencing an acute mental-health crisis should make a point to ask the dispatcher to send officers with 40 hours of CIT training under their belts.

Earlier this month, a 58-year-old Santa Barbara woman called 9-1-1, saying she was suicidal. Sheriff’s Office deputies managed to convince the woman to come out of her home. She emerged holding a large butcher knife to her neck, declaring she wanted to kill herself. Deputies sought to speak with her. Only when it appeared she “was about to make an attempt” to harm herself or a deputy did they fire one 40 mm foam baton out of a Less Lethal Launcher.

Hsueh highlighted this more recent case as doing it right. He declined to comment on the Carreño shooting, stating he had not been there. He didn’t know, for example, if the responding deputies had less-lethal weapons at their disposal. “Not every department has them; not every car has them,” he said. Officers, he noted, are trained to shoot to kill if someone armed with a knife gets within 21 feet. “You have to make split-second decisions. Ideally, you want to buy yourself time to consider other options,” he said. “But if a person doesn’t drop the knife and gets close, probably something bad is going to happen.”

In the meantime, Hsueh is pondering the future of his program. If part-time funding for Lee doesn’t continue after March, it’s unclear how he’ll manage. Undersheriff Melekian said he has some ideas up his sleeve but is not ready to unveil them just yet. The fiscal impact of the Thomas Fire and Montecito debris flow has not been fully assessed. In concept, however, Melekian supports the training program enthusiastically. “It makes a huge difference. It provides real knowledge. And where you have knowledge, you have less fear.”