After the Mudslides, What Does the Next Rain Hold for Montecito?

Thomas Fire Was Just Part One of the Rain Season

“It’s like a snow avalanche,” Kevin Cooper said, “but you might have 15 minutes of warning, maybe.” Cooper, a biologist with the U.S. Forest Service with years of burned soils experience, was talking about flash floods. What hit Montecito in the dark morning hours on January 9 was the worst of situations: an intense burst of rain striking steep, fire-denuded hillsides, and driven harder by strong winds. “Biblical” is the word Cooper used.

All of Montecito is built on top of ancient versions of the resulting mudflow. “Sediment comes out of these big, rare events,” said Cooper, “and fans out on flatter land, kind of shaped like a tiger’s tail waving back and forth.” UCSB geologists have studied Montecito’s alluvial fans for years, said Professor Ed Keller, who takes a great interest in fluvial morphology. “The youngest are still forming, and the oldest are 125,000 years old,” he said. (He’ll be talking about this at the Central Library’s Faulkner Gallery on January 25 at 6:30 p.m.)

The boulders were the big unknown for debris flow forecasters. They’d accumulated over the eons during rock falls up the canyons, and what it would take to start them rolling depended entirely on how hard the rain fell. How far they would tumble depended on what might intercept them, like the bridges and homes built in the past century. Of a debris flow full of giant boulders, “This county’s famous for them,” Cooper said. “But no one alive has probably ever seen one before.

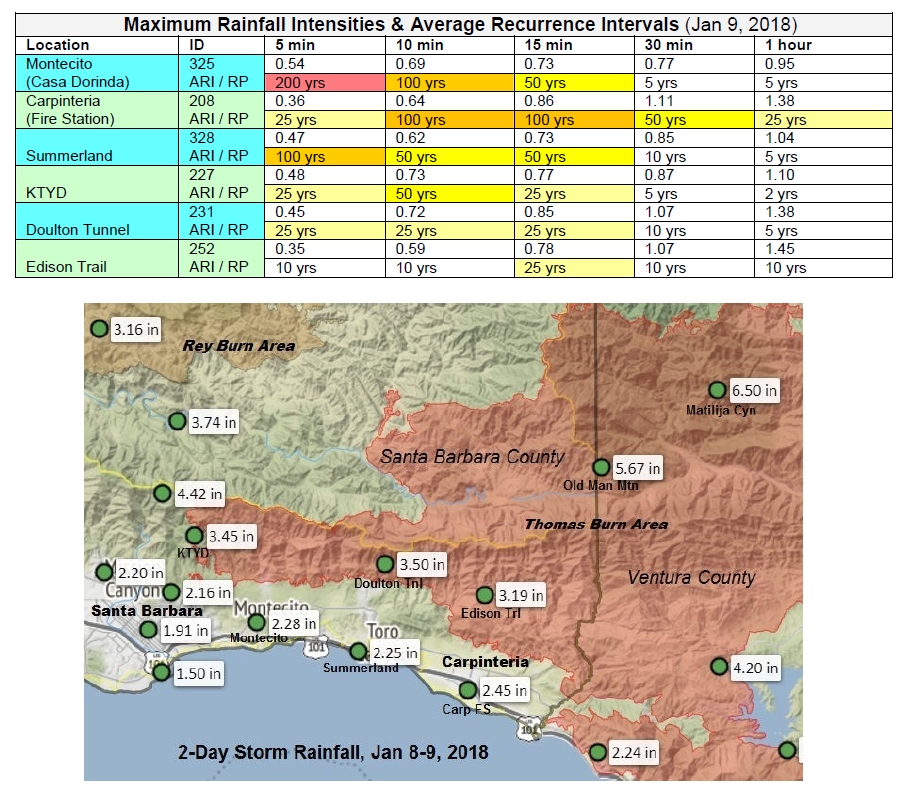

“This was a 200-year event. The overall rainfall was not extraordinary, maybe a few inches. It all depends on how it falls,” he said. In this case, a tropical storm coming out of the south ran up against Santa Barbara slopes running east to west. As the clouds rose quickly up the slopes pushed by the strong south wind, “strange vortexes develop,” said Cooper. “It cools quickly, making ripe conditions for wildly variable and off-the-chart rainfall intensities.”

If there’s any positive news possible from the deluge and devastation just four days ago, the 3.5 inches Lake Cachuma received increased the lake by about 212 million gallons. But the lake level — 701.98 feet — though slightly higher than previously, remains a good 50 feet below the spillway.

“The expectation was that rainfall of one inch per hour could kick something loose, but that it wouldn’t go very far. As slopes lessen, the debris drops out. For something to push all the way out to the ocean like it did had to be an extraordinary event,” said Cooper.

“I was there for some of those deliberations,” he said of the decisions made regarding Montecito’s evacuation areas. “There was a real and honest struggle on how to base decisions on predictions with wide probabilities. Do you evacuate 20,000 to 30,000 people every time a rainstorm comes?

“You have to base that on what you expect. If you have biblical storms, that’s just not predictable.”

Cooper, who works out of Los Padres National Forest, has been coordinating the watershed review ongoing since a few days into the Thomas Fire by the federal Burn Area Emergency Response (BAER) team. That review includes the new hazards wrought by the floods, the new channels the streams have dug for themselves, and the land-form and contour changes, he said. The most affected canyons he’d seen were Cold Spring, Hot Springs, San Ysidro, and Toro.

Also on site are geologists, hydrologists, and soils scientists with the state Watershed Emergency Response Team (WERT), said Len Nielson, a Calfire forester from Mariposa who coordinates that group. “We go out after a fire,” he explained, “to look at the watershed from the top of the ridge down to the ocean, to see how it might respond to future storm events. From there, we predict what’s going to happen in future storm events.”

The surveys begin with satellite imagery for a baseline of conditions. The area is then flown intensely by helicopter, and team members also walk in to evaluate the terrain, which is what they were doing when Nielson answered his phone. Among other things, they’re checking the organic material content of the soil to see how well it might hold together in rain, he said.

Now that the first storm has passed through, they’re outlining man-made structures still at risk, things like homes, bridges, and culverts, Nielson said, rejiggering their data for the new contours left by the flood. Part of their report, of which a draft is expected Monday, will analyze debris flow predictions for rainfall up to 24 milliliters, he said. That translates to almost an inch per hour. That’s far less than the awful cloudburst that may have triggered the mudflow Tuesday morning of 0.54 inches of rain in five minutes.

Santa Barbara County has measured rainfall intensity since the 1964-1965 rain year (from September-August), and only one other storm approached this level. In 1997-1998, El Niño-driven clouds dumped 0.48 inches at the Cold Spring Debris Basin, which sits about 2,000 feet south of the trailhead. The next heaviest rains recorded there were about a third of an inch a couple times. With the exception of 1998, the previous exceptionally hard rains fell under the once-every-25-years category. Even 1998 only approached the 100-year mark.

During the previous 39 years of recordkeeping, storms dropped an inch or more of rain within an hour a dozen times. The greatest rain-hour, 1.56 inches, occurred in 2003-2004. Interestingly, that was a dry year during which only 15 inches of Montecito’s normal 25 inches fell.

Although much rock and mud in the Thomas Fire zone has slid, another bout of heavy rain could be “like a conveyor belt with new material coming from above,” Cooper said when asked about next weekend’s minimal rain forecast. “We’re not out of the woods till the vegetation grows back,” he said. “That can take three to five years at the outside.”