Wilderness is often defined by its most noble landmarks — its peaks, valleys, rivers, and canyons. But sometimes these places also embody the people who explore and protect them.

My friend and hero, Jim Mills, was one of those people. And Santa Barbara’s backcountry was his place.

Jim’s childhood was marked with countless adventures in the outdoors. Starting around age 11, Jim would spend entire weekends exploring the backcountry. Back then, the area was known as the Santa Barbara National Forest, and it beckoned to him.

“I used to make up my packs on Thursday evenings,” wrote Jim in his 2010 autobiography, A Sense of Santa Barbara. “Then as soon as getting home from school on Fridays, I would go over to the bottom of San Marcos Pass and hitchhike over the mountain, sometimes not getting to the Oso Gate to start up the trail to Little Pine until after the sun had set.”

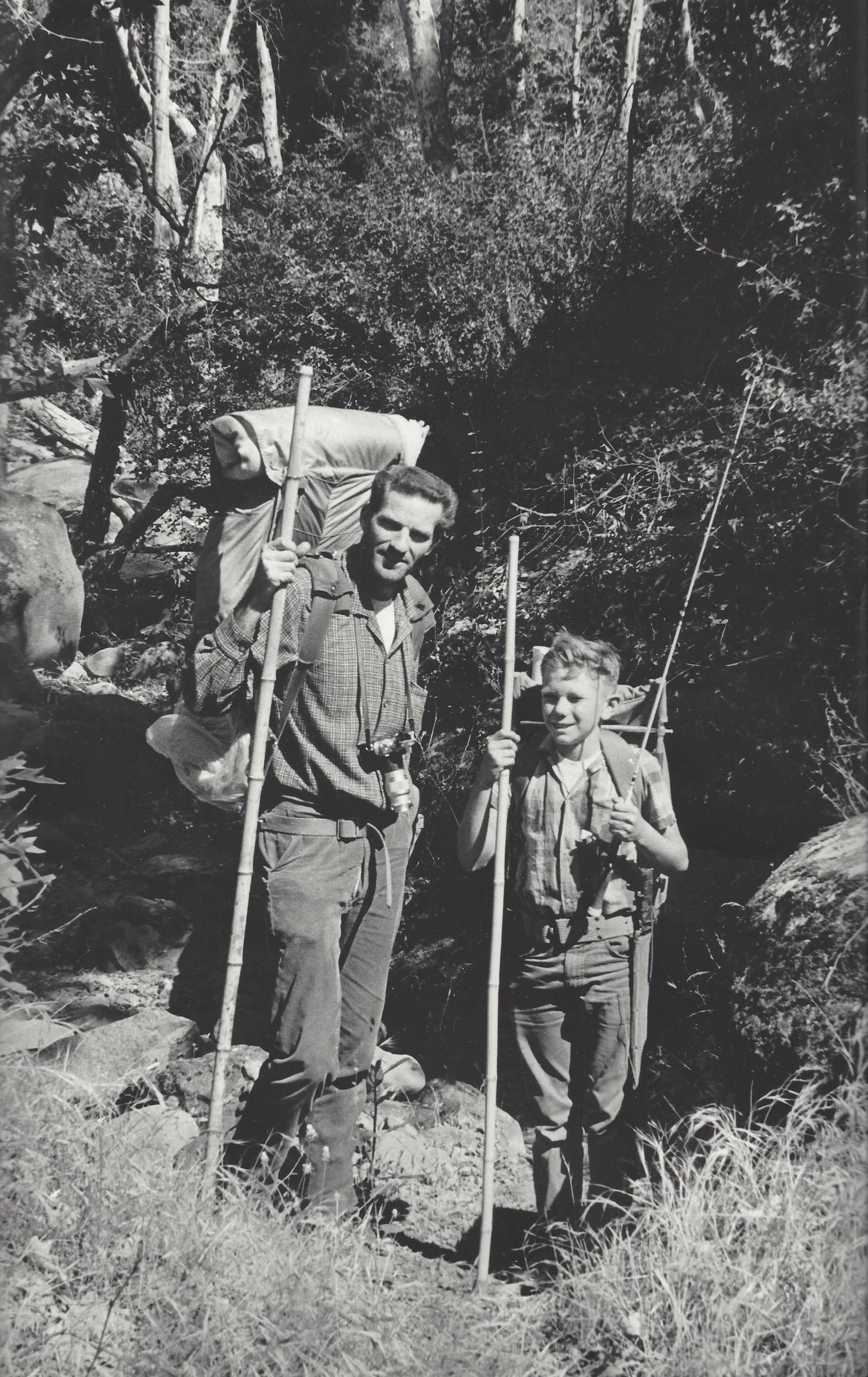

These early adventures formed the foundation of Jim’s lifetime of appreciation for our backcountry — one he would later instill in his children, grandchildren, and countless others whom he inspired along the way.

Jim landed his first job as a fire tank-truck operator in the northern portion of Los Padres National Forest amid Big Sur and Arroyo Seco. Later, he became foreman at the San Marcos Pass station, and then served in active duty as an aviation cadet in the U.S. Army Air Corps during World War II, followed by a stint of logging in the Pacific Northwest and oil drilling in Kansas before earning a doctorate in pharmacy from the University of Southern California in 1959. Jim eventually returned to Santa Barbara, where he worked as a pharmacist and met the love of his life, Alice de la Vega.

Jim and Alice married and raised two kids, and he relived his youthful backcountry adventures as family outings. During one excursion, he and his son Jimmy encountered a group of Scouts at a remote campsite just as snow began to fall. The next morning, after awaking to several feet of wintry powder, Jim made headlines as he helped guide the group to safety.

“First word on the whereabouts of more than three dozen persons stranded by a weekend storm in Los Padres National Forest back country was brought out yesterday afternoon by a Santa Maria Boy Scout and a Santa Barbara pharmacist,” began the newspaper article the following day, recounting how Jim walked 12 miles through knee-deep snow while leading an injured horse to a Cuyama Valley ranch. From there, he notified the Forest Service of the whereabouts of the Scouts — 15 jammed into a trailer at Santa Barbara Potrero and 25 packed into the South Fork Ranger Station cabin on the Sisquoc River — and they were all safely rescued.

Jim understood the value of providing his children with the same opportunities to explore nature that had defined his youth. On a fishing trip up Manzana Creek, Jim recalled in his autobiography carrying his young daughter Lindy over each stream crossing. “She never failed to giggle each time that we had that water flowing past underneath us. It never seemed to lose its novelty for her, and the memory of feeling her laugh or giggle vibrating into the back of my ribs is indelible to me.”

In the 1960s, Jim was invited to join the County Trails Advisory Committee along with local wilderness luminaries like Robert Easton, Kenneth Millar, Richmond Miller, Fred Eissler, and Dick Smith. They generated a groundswell of community support that ultimately resulted in the passage of federal legislation establishing the San Rafael Wilderness. Today, it spans 191,000 acres of Santa Barbara’s backcountry — permanently protected for current and future generations to enjoy.

But Jim didn’t stop there. After Dick and Ken passed away, he joined with champions like Anne Van Tyne, and together they convinced Congress to expand the protected wilderness area eastward. That area became known as the Dick Smith Wilderness. Jim also contributed to the establishment of Channel Islands National Park.

Further underscoring his commitment to preservation, Jim served on the board of directors of the Santa Barbara Trust for Historic Preservation for a quarter-century, chairing a committee charged with restoring the Presidio.

Jim’s commitment to land preservation was a perfect match for groups devoted to protecting Los Padres National Forest. He received the first-ever Wilderness Legacy Award from Los Padres ForestWatch, which I had the profound honor of presenting to him, and the Santa Barbara County Trails Council’s Lifetime Achievement Award.

“Behind our mountain backdrop lies a whole, nearly unchanged prehistoric wilderness world waiting to be explored,” Jim reflected in his memoir. “My best memories come from having partaken of much that that Santa Barbara world had to offer. My gratitude must go to those farsighted people who tried to maintain this rare inheritance for future generations.”

Even as he turned 90 last year, the places Jim worked so hard to protect — and the memories he forged within them — continued to inspire him daily. “I can count having known this backcountry in my earlier youth as one of my most valuable possessions,” said Jim, “and one from which I still draw sustenance by thought while sitting at home.”

As the wilderness reclaims Jim’s many footprints, these lands will remain protected for all time, and his memory will inspire a new generation of wilderness champions to continue to preserve the wide-open spaces that make Santa Barbara such a special place for all of us.

Happy trails, Jim.