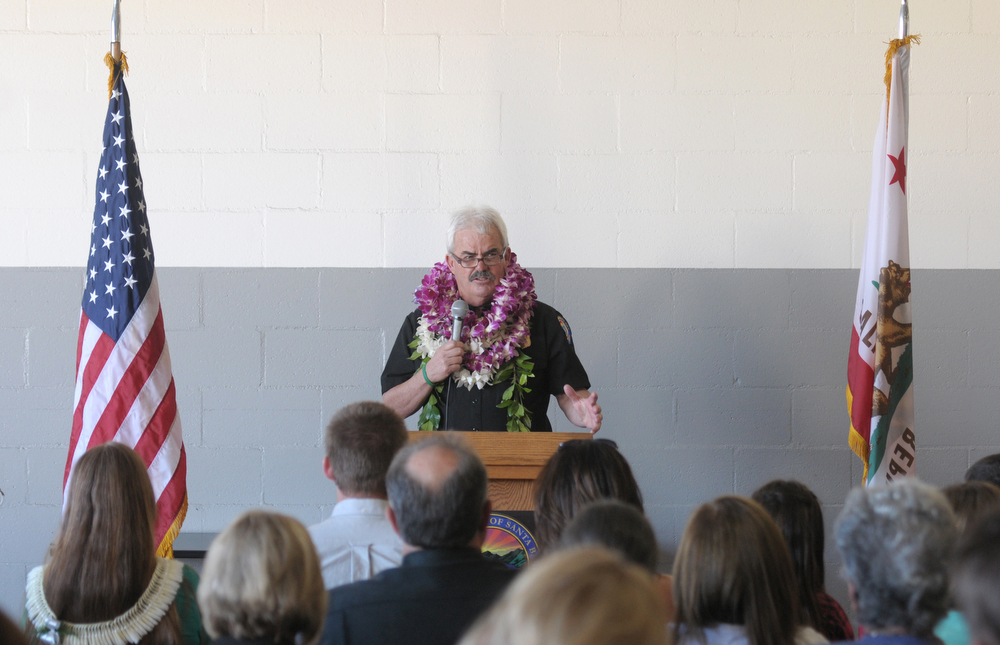

Santa Barbara City Fire Chief Pat McElroy turns 65 on March 17, which happens to be St. Patrick’s Day. It also happens to be the last day McElroy, a firefighter for 40 years, will wear his uniform. If all goes according to plan, McElroy will wear his Santa Barbara togs at New York City’s famous St. Patrick’s Day parade, accompanied by one of his two sons, also a firefighter, who just passed his probationary period with the San Diego Fire Department. Early this week, McElroy announced he was retiring — effective March 15 — after serving four years as chief and 36 years with the department.

“I’ve had some deaths of people who are close to me. Your time is not unlimited,” McElroy said. “We’ve got people here who can do the things that need to be done better than I can. Also, I’m running out of patience for certain things. The routine isn’t working for me anymore. I’m ready to do new things, other things.”

McElroy, long recognized as one of the most politically astute players within City Hall, ruled out a future run for office. “Absolutely, absolutely not,” he declared. “I’m interested in the things I’m interested in. When you’re an elected official, you don’t have that luxury.” By contrast, McElroy said, he’s affirmatively interested in a radical rewrite of how emergency services are currently delivered. He’s excited by plans — currently being incubated by a consortium of county fire chiefs — of adopting a unified dispatch service for all the different departments. Currently, each department has its own dispatch function. None, said McElroy, are aware of the array of emergency response resources marshalled nearby. Ventura County, by contrast, does.

McElroy is even more excited by an effort now quietly pushed by a group of fire chiefs to wrest primary authority of ambulance services from AMR, the private company that now holds the contract, to the fire chiefs. “Emergency medical delivery services has got to change,” he said. McElroy talks about embedding mental health and public health clinicians within the teams of first responders so they can deliver on-the-scene treatment. “Think about how much money we can save if we can figure out another way to deal with the 25 people we see who get an expensive ambulance ride to the ER eight or nine times a month,” he said. “If we can take those players out of the equation, imagine how much faster the response time will be for people having a heart attack or who just broke their arm. Think about how less congested the Emergency Rooms will be.”

To this end, McElroy helped convene a meeting with City Police Chief Lori Luhnow and Cottage Health CEO Ron Werft two months ago to discuss plans to embed Cottage clinicians with the Santa Barbara police officers assigned to the Restorative Policing beat, which focuses on the chronically homeless and others caught in the merry-go-round between the streets, jail, and the emergency room. “We all deal with the same people. But when was the last time all of us were in the same room talking about it?” McElroy asked. “Never.”

To date, noting concrete has emerged from that meeting, but McElroy is certain something will. “It’s the future,” he stated. “It’s just smart.” In this context, it’s hardly coincidental that McElroy just joined the board of Doctors Without Walls, a nonprofit group that focusses on the chronically homeless and mentally ill. It’s also no coincidence that Luhnow has too.

What role McElroy plays in making these changes happen has yet to be seen. The county’s contract with AMR is currently under review to determine if there are different, better, more cost effective ways to structure services. City and county administrators worry that with the changing health care finances promoted by the White House of Donald Trump, they might get stuck with additional costs. To the extent local fire departments are unified behind this initiative — modeled on an approach pioneered in Contra Costa County — it’s in large part because McElroy helped bring them together.

Such unity has not always been the case, as McElroy can attest. In one of the first structure fires he responded to, McElroy recalled city firefighters battling one end of the blaze with county firefighters battling the other side. “We were fighting the same fire and we weren’t talking,” he said. “It was crazy.” McElroy says he came of age as a firefighter as California fire agencies were perfecting the arcane but crucial art of “Incident Command” out of which has emerged a seamless choreographed cooperation of multiple firefighting agencies capable of shifting and adjusting as the size of the fire changes.

Over the past 30 years, McElroy’s has been the most visible face of any fire department. He’s also been the most accessible. As head of the firefighters union, McElroy cultivated close political and personal relationships with elected officials and with the media. He worked with the Police Officers Association, creating the now fabled “guns-and-hoses” coalition whose endorsement was much coveted by anyone serious about seeking public office.

As McElroy sought to move up the food chain into upper management, some city administrators expressed serious trepidations about his union affiliation. Despite such concerns, McElroy’s skill set, connections, smarts, and political acumen proved irresistible and he was sworn in as chief in 2013. At the time, it was uncertain just how long he’d stay before retirement.

In 2016, McElroy led the charge on behalf of a bill to reduce delays built into the way 9-1-1 calls made on cell phones were routed from cell phone towers to emergency dispatch centers. The details of the bill were forbiddingly technical and hard to explain. McElroy — keenly aware of the need to tell a convincing story — made it painfully simple: why is it that Domino’s can deliver pizza to your house in less time than it takes emergency responders to arrive? McElroy worked closely with then State Assemblymember Das Williams to get the bill passed, but not without experiencing serious resistance and foot-dragging from California’s Office of Emergency Services. “He was so tenacious. We couldn’t have done it without Pat,” said Williams’s former assistant Hillary Blackerby. “We wouldn’t have known it was such a serious issue if it weren’t for him.” Blackerby said McElroy was ready to fly to Sacramento at a moment’s notice to fight for the bill. “I never want to be on the other side of a fight from Pat,” she said. “He’s a tough one.”

It’s no coincidence McElroy’s retirement announcement comes shortly after City Hall’s most recent elections and the passage of Measure C, the sales tax increase estimated to generate $22 million a year for unmet infrastructure needs. It would be an overstatement to call the Measure C campaign McElroy’s last hurrah, but he played a crucial role as campaign spokesperson as well as strategist. While the campaign was low-key in the extreme, McElroy’s part was significant. “He knew who to call, what pitfalls to avoid, and who to ask for money so that a credible campaign could be waged,” said City Administrator Paul Casey. “That was not easy to do. He was important to the inner team.” Casey was impressed McElroy used his political capital on behalf of a city-wide initiative for which the fire department would be just one of many beneficiaries.