OTOjOY Makes Live Music Accessible to All

Thomas Kaufmann Is Changing Concert Experiences One Loop at a Time

When neuroscientist Daniel J. Levitin wrote in his scintillating book This Is Your Brain on Music that “music is … part of the fabric of everyday life,” he was spot-on. Music provides the soundtrack to our existence, from our mundane comings-and-goings to significant life events. The lilt of a melody can sear into your mind, conjuring a memory each time it’s heard. Music can stir the soul and change your mood in an instance. It is provocative, whimsical, beautiful, heart-wrenching, serene, intoxicating.

Imagine, then, what it’s like for people who are unable to fully revel in music’s bounty due to hearing loss. Thomas Kaufmann has, and as a result he founded OTOjOY, a Santa Barbara–based company that provides auditory-challenged concertgoers a high-quality experience through hearing loop technology. (More on that later.)

The inspiration for OTOjOY — the name is a play on Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony movement “Ode to Joy” — came surprisingly. In 2012, Kaufmann was earning a master’s degree in chemistry from UCSB when he attended a breakfast with friends that forever changed his career trajectory. While dining, one of them, a professional photographer, complained about his ears still ringing from the prior night’s shoot at the Santa Barbara Bowl. When Kaufmann asked him if he wore earplugs, he said, “No, because then I can’t hear anything, and I want to enjoy the sound.” Kaufmann responded by saying, “You have to wear the right ones.”

A lifelong music aficionado, Kaufmann had created a successful deejaying business by age 18 in his native Germany, so knew firsthand the importance of wearing hearing protection. In fact, he has a custom-fitted pair of earplugs always on hand, which he showed his friends. Noting his passion regarding hearing-loss prevention, Kaufmann’s friends challenged him to start a business that addressed the issue. He took them up on it and began sowing the seeds for OTOjOY.

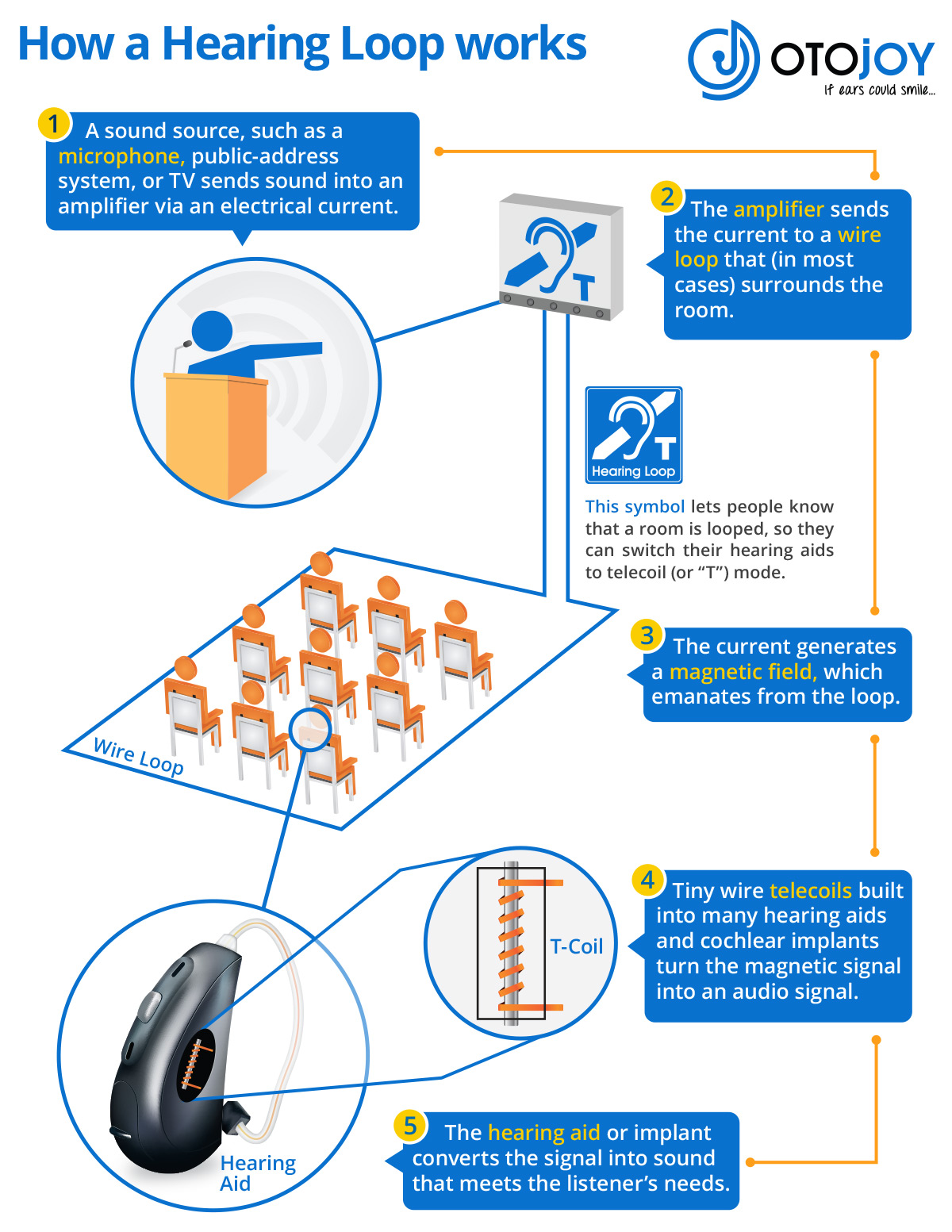

Kaufmann dove into his new venture by doing extensive research on hearing protection, audiology, and hearing aids, with the intention of creating his own line of custom-fit earplugs. While still in the data-gathering phase, Kaufmann learned of a technology called an audio-frequency induction loop (aka hearing loops) from Claudia Herczog, then president of the Santa Barbara chapter of the Hearing Loss Association of America, who found out about it at a national conference. “A hearing loop is an assistive listening system that transfers sound wirelessly to people’s existing hearing aids,” explained Kaufmann. “People who already have hearing aids equipped with a t-coil can just press a button and wirelessly receive the signal from a public venue that has a hearing loop installed.”

Hearing loop technology is based on electromagnetic fields, which have been known about since the 1700s. However, it wasn’t until about four decades into the 20th century that their use in hearing assistance became clear. In 1938, British telephone and sound engineer Joseph Poliakoff invented the telecoil, a metal rod wrapped by an extremely fine wire. The t-coil, as it is commonly called, can detect the signal emitted from an induction loop and translate it into clear, distinguishable sounds. When an induction loop system is installed in a venue’s seating area, then, folks within it hear the music at an optimal designation for their particular hearing loss.

Kaufmann soon discovered that, in the United States, not much importance has been placed on improving concert experiences for people with hearing loss. While loops were being employed in the U.K. and Scandinavia fairly regularly, few U.S. venues were outfitted with them, and most people had never heard of the technology. The majority of places, in fact, are poorly equipped to accommodate folks, and even when they can, the devices tend to be FM-signal-based receivers with headphones or “neck loops,” which are clunky and carry a social stigma.

Kaufmann decided to change that statistic. For the past five years, he and his team have been responsible for looping a plethora of venues in Santa Barbara, including the Arlington, the Lobero Theatre, and the Bowl.

Looping In Listeners

The largest outdoor amphitheater on the Central Coast, the Santa Barbara Bowl boasts a state-of-the-art sound system, yet the venue only offered the aforementioned FM-based assistive listening devices when Kaufmann met with the Bowl’s board in 2015 to discuss installing a hearing loop.

“[When] we were approached by Thomas, [we] talked a lot about the opportunity, but it was new to us at that time,” said Rick Boller, the Bowl’s executive director. “We had had an assistive listening system, but it was pretty antiquated. [Attendees] had to request the system if they were coming to a show, ideally in advance, because it needed to be set up through the soundboard, and then they needed to be relocated into an area in the proximity of the system so that they could access it. And then the quality of it wasn’t [very good],” he said. “So we agreed to loop a small portion of our facility, which was our preferred section at the time because it’s near the soundboard, more central …. We did that for about a year, and it worked really well.”

One person who was particularly grateful for the upgrade was Nora McNeely Hurley. A longtime Bowl-goer, McNeely Hurley had stopped attending shows because the sound was untenable. “I was forced to give up going to concerts as I could not make sense of music,” said McNeely Hurley, who has reduced hearing capacity. After OTOjOY installed its loop technology, things changed for the music fan. “I could discern each instrument being played and heard them clearly thanks to the hearing loop,” she said. “Radiohead provided a brilliant [re]introduction to sound.” She was so thrilled, in fact, that McNeely Hurley and her family foundation, the Manitou Fund, underwrote the cost to have the entire venue looped.

The Bowl is now focusing on letting the community know about its updated assistive listening system. “We’re reaching out to organizations in town and trying to get out the word to folks that maybe stopped coming to shows because they weren’t able to experience [the music] the way that they wanted to,” said Boller. “The cool thing about the hearing loop is that it eliminates the need to request in advance and sit in a certain area. There’s equal access for everyone.”

More than 60 million Americans, 23 percent of the population, are affected by hearing loss in at least one ear, according to Johns Hopkins University, and even an estimated one in five teenagers experiences some degree of hearing loss. When the damage is slight, the listener may not even know what they are missing sonically (e.g., chordal nuances, high-end register details); when it’s extensive, the world can be a confusing cacophony of muddled sounds. Since hearing loss is not visibly detectable by others — and because many who are affected don’t reveal their need for accommodations due to shame associated with this disability — venues often don’t provide high-quality assistive listening devices.

For Kaufmann, OTOjOY has been about correcting that through education and changes in convenience. “Ever since we started out, our primary goal has been to spread awareness about the lack of accessibility for individuals with hearing loss and to educate people about available technology options,” Kaufmann wrote in a recent essay he penned for Hearing Health Magazine. “Almost every time we demonstrated a hearing loop with someone’s favorite piece of music, they were in tears. In fact, one woman described that if she used ‘just’ her hearing aids, she would hear the world in black-and-white, only gleaning the facts and information. With the help of a hearing loop, however, her world would instantly change to Technicolor, and she could hear levels of emotion and musical nuances that she hadn’t perceived in years.”

This past year, OTOjOY has had huge successes. Not only has the company installed hearing loops in venues throughout California and Arizona, but it also began looping outdoor music festivals, such as Stagecoach, the Oregon Eclipse Festival, and Coachella. (Hear the sound difference of the looped Lady Gaga here.) Although the company is making headway in the festival arena, it is still an uphill battle. For example, despite offering to loop several shows for free at the recent Austin City Limits, Kaufmann’s offer was declined.

Yet for every setback, there is a move forward. OTOjOY recently looped an Odesza show in Berlin, and the group’s “production manager and sound engineer was incredibly excited about our work,” said Kaufmann. As a result, the band is onboard to help get the word out about hearing loops. “We are a huge proponent of the cause,” said Odesza’s Clayton Knight, who studied physics at university. “It’s crazy to hear how many people go through minor to severe hearing loss — the numbers are pretty outrageous …. The hearing loop is a pretty basic concept being used in a unique way,” Knight continued. “I’m surprised it took us this long to get to that. The technology and the theory have been around forever. Moving forward, having this system in every venue would allow a huge other fan base into the mix again.”

In addition to installing hearing loops, OTOjOY offers high-fidelity earplugs and recently released OTOjOY LoopBuds, earbuds that work in conjunction with a phone app and allow users to access hearing loops in venues to listen to music and speech with enhanced clarity. LoopBuds has already garnered a New Product Award from WFX and a 2018 CES Innovation Award. The company itself is a 2018 Edison Awards nominee and a semifinalist in the Arizona Innovation Challenge.

In the end, Kaufmann’s crusade is summed up in OTOjOY’s succinct slogan: “Creating equal access to sound. For everyone. Everywhere.” As for what’s to come? Kaufmann said he plans to continue to “work toward a future where everyone’s world can go beyond just black-and-white to being fully, wonderfully, and deeply Technicolor.”