The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island, the real-life figure behind Scott O’Dell’s beloved 1960 novel Island of the Blue Dolphins, is a fixture of local history. She lived alone for 18 years on the most remote and arguably least hospitable of the Channel Islands until the sailor and otter hunter George Nidever brought her to Santa Barbara. Little is known about her life on the island, but she has continued to fascinate readers and researchers alike. And on Monday, October 2, the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History will premiere a new documentary by filmmaker Paul Goldsmith about the Lone Woman.

Goldsmith has had a long career in Hollywood, working on documentaries, music videos, and commercials. Then, he said, “I got old and I started making my own films. One plus is that you get to do exactly what you want.” Goldsmith discovered his interest in California’s Native American stories while working as the director of photography on the PBS series We Shall Remain, which documents Native Americans’ experience of U.S. history.

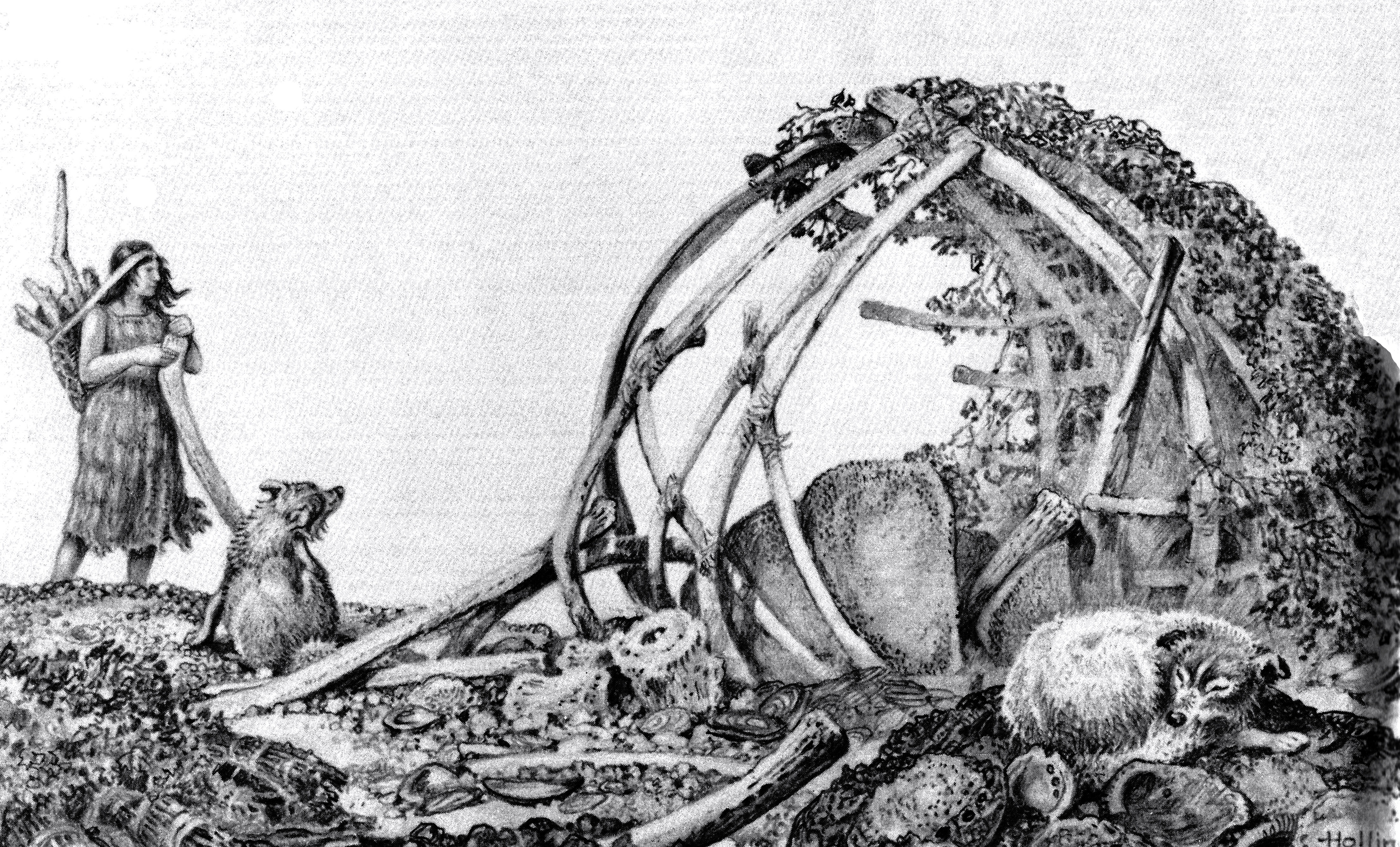

The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island is the final installment of Goldsmith’s three-part series on Native Americans in California. The first, 6 Generations, narrates the family story of Ernestine De Soto, a Chumash elder. “It’s a story of how women are really the chain in a culture of survival,” he said. The second film, Talking Stone: Rock Art of the Cosos, explores the petroglyphs at China Lake, currently the site of the Naval Air Weapons Station. The rock paintings are “the oldest art in California,” Goldsmith explained. For his new film, Goldsmith visited San Nicolas Island, filming what was then the Lone Woman’s newly discovered cave. He interviewed archaeologists and researchers, filmed extant artifacts, and used the details of the natural environment—along with some reenactment—to bring the Lone Woman’s story to life.

The Santa Barbara Independent caught up with Goldsmith to talk about the project.

How did you get interested in the Lone Woman? California has sort of ignored its history in many ways. I come from the East Coast, where we take our history much more seriously. For one thing, California is all about coming out here and starting a new life. That’s what it has been traditionally, right back to the gold rush. People often don’t even know the history, let alone value it.

There was this Lone Woman story, and I thought, you know, [it’s] amazing that they haven’t made a [documentary] film on it. It’s extraordinary, based on a true story, but no one’s done a documentary.

All of the films that I’ve done, since these are projects I’ve generated on my own, are films that I thought it would be fun to make. I wanted to go to San Nicolas Island.

How did you decide to approach the topic? I’ve made a short version for kids, and my goal, aside from the PBS film, is to get the short version, which is 20 minutes, designed for 4th grade, to every 4th grader in California — to every 4th grade teacher, 4th grade student, every parent of a 4th grader. And one of the ideas is, this is the first, in 4th grade, this [Island of the Blue Dolphins] is the book they read as their first chapter book. I don’t remember what mine was, but I do remember the shock of turning the pages, and each page, there were no pictures, there was just print.

But rather than being too specific, what I want to celebrate in the film is how extraordinary that this story about a woman — not a man — a Native American, not some white general, a person whose name we don’t know, whose language we never learned, who we don’t even have a picture of, has survived over all these years and means a lot. People connect to her. She was extraordinary — there was something, not only in her story but in her person, that transcended time and left a message and a story that we’re still talking about now. And whether you come at it from the book, or whether you come at it [as] the archaeologist trying to dig up her artifacts, or you come at it [as] the person trying to research in baptismal records — whatever your approach, it’s honoring this extraordinary person, and that’s essentially what I want people to carry away from the film.

What were some of the challenges of making the film? The biggest challenge, of course, is my star. I have no pictures of my star, I have no recordings of my star. Movies are about people. How do you bring her to the audience? So I did a tiny number of reenactments; the island itself stands in for her a little, with all of its animals. But certainly that was the hardest thing. But one thing that you’ll see in the film that is kind of miraculous is when she got on the boat heading back to Santa Barbara and a huge storm came up. She started a chant — they call it a song, but I think it was a prayer — that she sang, again and again and again, until the winds relented. Well, that chant/song/prayer was remembered by one of the Chumash crew members, and when he was an old man, he sang it, and another Chumash who was young, Fernando Librado, heard it and remembered it, and when Fernando was an old man, he sang it for [anthropologist] John Peabody Harrington, who had the very earliest recording device — an Edison recorder that recorded on a wax cylinder. That song you can hear at the Santa Barbara Museum [of Natural History], and I have it in the film. And in a sense, realistically, it’s a distant echo of her voice.

4·1·1

The Lone Woman of San Nicolas Island will screen in the Museum of Natural History’s Fleischmann Auditorium (2559 Puesta del Sol) on Monday, October 2, at 7 p.m., followed by a panel discussion that includes Paul Goldsmith, Chumash elder Ernestine De Soto, archaeologist René Vellanoweth, historian Susan Morris, and Dr. John Johnson, the museum’s curator of anthropology. Visit sbnature.org/tickets.