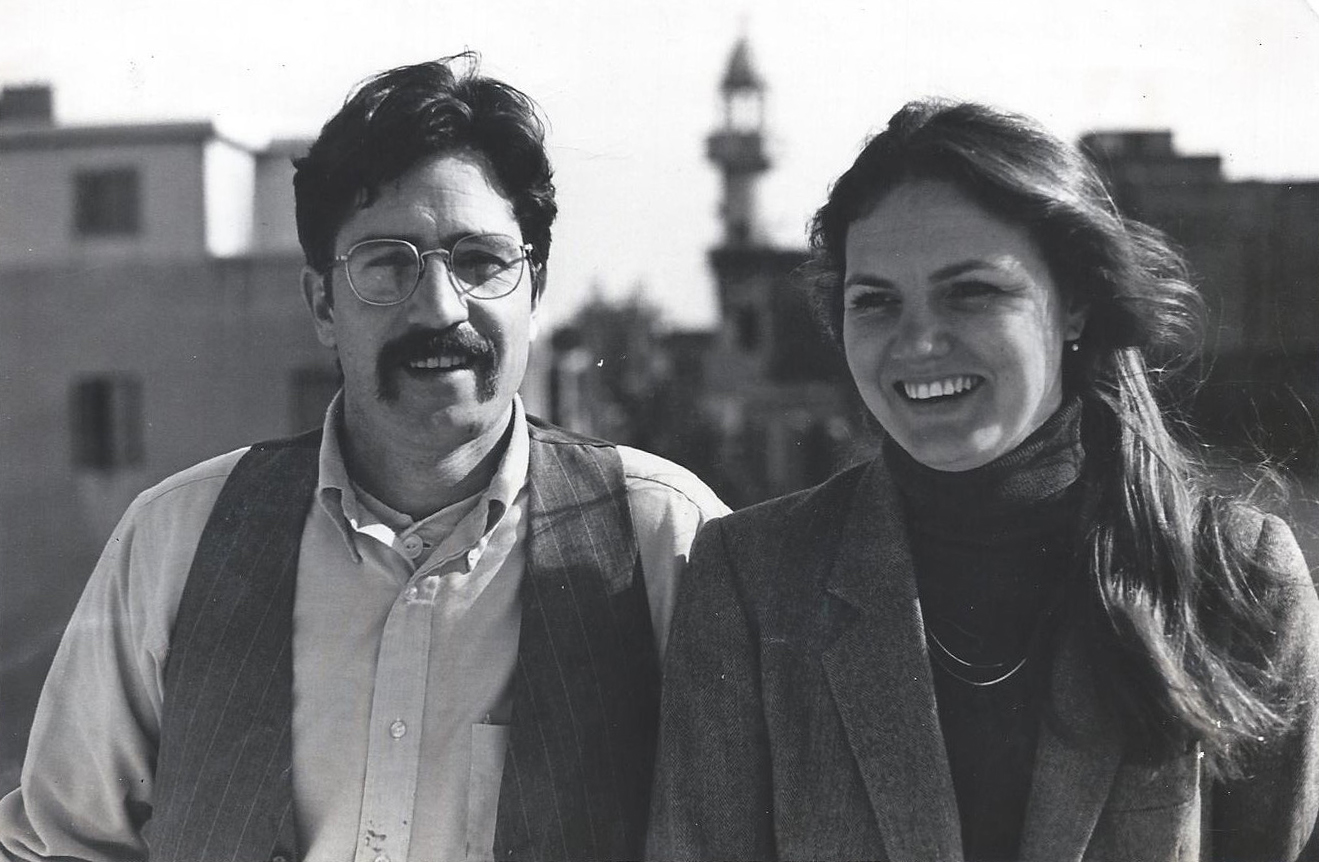

Ralph Lowe, who contributed to The Santa Barbara Independent for all too short a time, died on June 10, 2017. His life took him — and wife Georgene Lowe — around the world into war zones and refugee camps, some of which he recalled in memoirs written during his last months in San Miguel de Allende. The writing here is excerpted in this week’s print edition.

We are down here in Steve and Brenda’s palacio with its paradise (Arabic, it turns out, for “walled garden”) waiting out DNA testing, genome positioning, trying to find the high ground from which to fire upon, or at least snipe at the shadow army that seems intent on killing. It is a patient, intent militia, impervious so far to nuance or shock and awe. The greater field of battle, my body, remains deeply scarred and traumatized by fire both friendly hostile — inexplicably nasty, malicious and without conscience, guidance, ideology, or history. This is not a bus running over me on Broadway but rather me killing me. We have been to the mountaintop (the Mayo Clinic), danced to Doctor Gupta in Santa Barbara with his macabre tune, and it all comes down to the same end, and that is, barring a miracle of DNA identification, I’ll be dead within the year.

Georgene asked me to write some stuff down before my collision with that “Rough Mountain, death.” The following will be incomplete as are all such attempts at summation must surely be. I will leave out a great part of the cast, whole eras, road trips, lovers, failures, and triumphs. I will spend an hour a day or so doing this and no more because there is much to still see, smell, hear, but, I fear in my case, not taste, before my denouement slips into high gear, and then, who knows what?

San Miguel de Allende, Guanajuato State, Agua de Ojos, Mexico

Not far from here, Neal Cassady was killed one night crossing the night track, no doubt drunk on tequila and his visions which Kerouac would steal for his own. He lived, talked, drank, seduced, talked some more, and was insatiable for all that there might be, and he didn’t want to miss any of it. He seemed like a good role model then and now.

And so it was years on the road with Tim, Russ, Georgene, Bob Richie and his alcoholic dog Jim, Steve Catalano, and Danny Ringle who changed his name to Montana and drank himself to death in Wyoming. We hopped freights, hitchhiked for thousands of miles, met the great and the small, and learned to live with the blank horizon impaled by Route 80 or 90 and shards of 61. We learned about patience and its limits. We read Whitman and Kerouac and Sartre and Nabokov by hobo junction firelight or in the stagnant sun of the Midwestern endlessness. We learned the value of conversation, took no pictures, didn’t want a camera, made long distance phone calls to girls using John Lennon’s credit card number which was announced from the stage at a concert in the Haight by some feckless Wavy Gravy type who lived to undermine the system whenever and however he could. I respected his intent but don’t and didn’t approve of Lennon as a cog. The phone booths on the edge of truck stops would eventually fog up and there I would be trying to fend off the cold and sweet talk some poor girl who didn’t deserve such use. I will avoid the word Alas as often as I can but I fear I can’t avoid it enough.

Dunn School

I was born, the son of a surgeon and a singular woman who bore four of us boys, and then grew up in the fragrant humidor that was Orange County, California. The county was well named. There were millions of orange trees bearing heavy fruit and blossoms. There were no freeways. My dad, along with his brother in law, Uncle Sid, built one of the first of two or three motels across the street from what would become Disneyland and the epicenter of the decay of paradise. We watched them build a phony mountain and then lived it its shadow. I was in high school before I realized that we had been witness to an all-out assault on beauty by the armies of greed.

I published an underground newspaper, The Armadillo — named after Steve’s stuffed one that he has kept as a talisman all these long years — then later betrayed myself and the rest of the editorial crew by blabbing out my part in order to impress a girl who would never have even deigned to look at me until I was the desperado of the moment, the conscience of a generation and even cool. I was part of the vanguard of what we all wanted: change, disruption, new possibilities, and the withering away of a past that was oppressive, without imagination or music. The administration at Sunny Hills High School saw us not as visionaries but pretentious, adenoidal troublemakers who had gone well beyond the pale and there should stay. That is how I came to Dunn.

At Dunn I met Tim, and we would be fellow travelers, confidants and sounding boards for each other for the rest of my life anyway. We hitchhiked across America some seven times, and all of North Africa (with Russ on The Trip) which looked remarkably like California, hopped freights, huddled in the rain, and waited for the car that would save us to make its slow tantalizing appearance at the top of the horizon. At Dunn I was gifted with a group of teachers whose expertise, imagination, and zeal would make up the man I wanted to be and, I hope, became. I lived in a water tower and learned the virtues of living without corners. I saw teachers like Mr. Thatcher and Mr. Gill and wanted to be them.

Teaching is a sacred endeavor. Children trust that you guide them and tell the truth. They begin to have intellectual powers they never imagined, and you get to show them the way: Don’t read Frost, read Yeats. Shakespeare is the shaper of mankind itself — his wisdom and humor far more useful and reasonable than anything to be found in all the gospels. Listen before you speak. Things are rarely as they seem, compassion, and awareness are synonyms, and so on.

We graduated. I went to Salt Lake and the University of Utah with Dray Freeman and Russell with boots already firmly on the ground. I fell in with hippies and the like, and our belief was that we were immortal and responsible for keeping iconoclasm, dizzying imagination, and hope alive in an America we saw as greedy, dangerous, hidebound, and suspicious.

I met lots of girls. They were in the full blush of youth, and I thought them perfect and scary and mysterious. Their beauty is the standard still by which I make most aesthetic assessments. They are always here, always with me, and I wish there were some way to let them know that I was the clay or dough they kneaded without even knowing it. They are my pantheon of personal poets — speakers from beyond, keepers of deep knowledge, and the agency by which serenity might be doled out to us in the rare, odd moments when we put on the alpaca woven with grace.

College was boring. I got straight As, and it ruined me for academe. I was itchy in the classroom, impatient on the street, and then I met Courtney Morgan who lived in Idaho Falls and went north with her where I worked in her father’s factory making boxes on an infernal machine and learning to tie canvas spud sacks. When I left, Morgan was crying as she handed me a golden needle in a leather bag in case I ever needed to fasten a woven material around something — anything — and that wouldn’t come up until the Sudan where part of my duties was bartering for shrouds within to place the wretched of the earth after the short, eviscerating opera that were the lives of refugees in the Horn of Africa where they say was where Eden was though I never saw anything to support that notion. There we were in the Land of Nod where Adam and Eve learned to need, and I had left Courtney’s needle at home and have yet, even now, to find it.

I went to Fullerton, lived at home, worked two jobs, and put all my money in a shoe box.

In the Wind

I met Tim in San Francisco and we a hopped freight out of Sparks, Nevada and then hitchhiked to Manhattan to try and meet Kerensky (the ad hoc premier of Russia, who was exiled to America.) We caught he hippie airline — Icelandic Air $200 NYC to London — and we were off. In the wind.

We lived in barrack-like hostels in London and Tim went off somewhere and I hitched north to Wales and Dylan Thomas’ village of Laughrne where I walked, peeked into different corners of his biography, and ate lunch next to his grave. I think I was there for a week and met Tim and, somehow, we started going south.

The plan was to meet the daughter of a guy who had picked us up in Nevada and driven us to Chicago (or something like that) who showed us pictures of his beautiful daughter who was in the Canary Islands, and so that is where we headed. Somehow we got stuck in Athens. We lived in the Plaka on rooftops and sold fried egg sandwiches to hungry hippies using a portable stove and a skillet from the flea market in Monasteraki. For some reason, we finally got on a plane and landed in Cairo during one of the Israeli wars where all the headlights were painted and where sirens battled the calls to prayer. Then we moved to Marrakech and lived in an apartment beneath the Kartubia Hotel not far from Djelma el Fna “the market of the dead” which is the most complicated, outrageous, and fascinating market in the world if you don’t count Chichicastenego in the mountains of Guatemala.

I wrote poems, and Tim painted above a courtyard where the staff beheaded chickens and paid no attention us. I had a part-time job as a shill for one of the shopkeepers deep in the souk — accosting English-speaking tourists and feckless hippies. At night we were upstairs at Rex’s Milkshake Bar where I never saw a milkshake through the smoke and the raucous debut of Let It Bleed — a watershed moment for rock and roll — and then crept through the moonlit streets avoiding beggars and cops. We were there for months.

Russell had taken his LSATs and wanted to do some traveling before law school, and he met me in a bayside café in Tangiers one afternoon and awoke his first Moroccan morning with a fat chicken on the raised metal footing of his bed. We went back to Marrakech to find Sherif of the Starred Boots who was killing himself with kif and languor. We thought maybe we could save him. We were very young.

We were going to go east into the Atlas Mountains and then to the Sahara, and we wanted Sherif to come and shake the kif and maybe find something to live for. He had never been out of Marrakech. He of course had his own stash, and so we just travelled. We found a camel market deep into the desert where we heard of a magical place and that was how and why we took an ancient bus to Todra Gorge.

Two huge tents were at the bottom of the gorge into which one hour of daylight and one of moonlight shone. The tents were traveler’s oases, resplendent with cushions and pillows — an eighteenth century white man’s version of an Eastern harem — and daily plates of boiled eggs and couscous. We were instant celebrities and met all of the local celebrities: The Man Who Died and then Woke Up in his Rock Grave just as a woman came out of the hills with a bundle of firewood on her back and the Chief who took us to see the moon in the hour we could and, through Sharif, I told them that an American had been there, on the moon — the most sacred of all images in a religion that shuns iconography is any form. I told them, furthermore, that there Americans had driven a little car and hit golf balls. I was a fool and I thought they might just kill us all as blaspheming infidels, but they just went silent and disappeared to wherever they lived. We could hear their scimitars chiming in the night. We left, Sharif stayed, and the next stop was Algeria.

And after Algeria there was Tunis and Carthage, and then we flew to Cairo and made our way up river to Luxor, Karnak, the Valleys of the King and Queens, and Shenaboo who would sell us omelets and opium in his hut in the wheat fields well beyond the zone where foreigners were allowed. We spent hours staring at the Nile. I met an Australian almost beautiful girl named Zan who wore a wide embroidered belt that took whole anxious moments to untie. We lived where archeologists used to. High ceilinged rooms deteriorating as you watched, then biked to the market for ice and Zotto’s rum which we drank on our balcony where we talked about everything.

Then it was sort of over. We flew to Greece, Tim went one way and Russ another. I had met a girl named Ellen in Cairo, and the two of us hitchhiked from Athens to Venice, accumulating stories by the kilometer. I met Tim in London and then to New York and Route 80 that draws you right into San Francisco.

Now came more college and more dropping out and the two journeys to Alaska where I was a bartender by night and a Housekeeping Manager by day in the one hotel in what was then called McKinley, or unemployed, sleeping on the floor at Tim’s in Anchorage while he worked the docks and with Jane who worked the bars and would return each morning with a bag of silver dollars.

An Adze and a Bowling Pin

And there were three seasons and a long winter on Lummi Island in Puget Sound. We were reef fishermen, and there was no one like us in all the world. Russell was a master and a legend at spotting fish and Tim or Dray were pretty good but I was hopeless but no one seemed to care. The winter on Lummi was dark and rainy and cold all of the time. I hauled cedar logs off the beach and up the hill to where I had a modest cover under which I would chop out cedar shakes with an adze and a bowling pin, and then hitchhike to the ferry and across Gooseberry Point to Bellingham where I sold them and picked up my unemployment check twice a month. There might have been a hundred people on the island. It meant days without talking to anyone. Just books and firewood and early Dylan on scratched vinyl and “the rain that raineth every day.”

At the end of my third season I decided it was time to do something else and so planned a trip south where Tim and Annie were living in Eugene. At the farewell party a troll named Dave Ritchie who had been on the island for only a few weeks rose to my fireside challenge that it was “impossible to offend me” and whispered something that made me shudder and gag. The next day we caught a freight with Jim, Dave’s drunken dog, and rode it straight into Eugene.

Annie and I got work in Beetland on the 3-11 shift and stood over conveyor belts culling and nitpicking the boiled and sometimes raw vegetable which to this day I find noxious with an echo of boredom, inconsequence, and failure far too soon. We slept on Tim’s floor then moved to Apartment Zero next to a Dairy Queen. Apartment Zero had a couch, no beds, and a door that opened into a wall. We slept on the floor and read on the couch. Then one night Tim took us to a birthday party in Springfield, and I met Georgene.

I was dazzled by her. Still am. Smart, kind, funny, beautiful, centered, cool, unafraid, and curious, she was different from every girl at the party. She is the only one I remember even seeing. She was living with Ed Hogan, and this was a problem. We courted, she moved to Marin and Ed. I followed soon thereafter in search of her and Claire Simpson, the beauty who didn’t ever take me seriously and who herself ended marrying a Colombian grave digger in Salt Lake. George left Ed (we, Ed and I, became fast and good friends and later while a teacher at Dunn I married him to the lovely Amy in the schoolhouse on campus with a reception following at our house). But long before that we moved to Utah to pursue my elusive degree in English Literature with a minor in English History. I didn’t learn a whole lot — never did in college — but got the paper and started sending resumes all over the world.

We were married in Steven and Brenda’s living room on A Street. Tim was my best man. He and some friends bought us a pure bred basset puppy as a wedding gift. I met the dog in the morning, and no one ever saw him or her again. Everyone was there. We slept at the Hotel Utah that night, and Georgene cried. Then we flew to Mexico and Isla Mujeres for a two-week honeymoon that lasted a month. We came home broke and ready for the next step to take or the next huarache to fall.

Paralyzed in the Yucatan

I took a job as a teacher of English and Psychology at the Vershire School in Vershire, Vermont, on Judgment Ridge. It was a school for “bright underachievers” who came mostly from Manhattan or Long Island. They were, of course, drug-fond and fans of the Grateful Dead and Country Joe and the Fish. I learned to teach in that cauldron where the students were sometimes smarter than you but were befogged and sad beyond their years. They were readers. The wanted more and more Freud, they liked to dream and then to dissect those dreams.

After my second year I was named “Jefe” of the annual pilgrimage/evacuation. The Headmaster couldn’t keep up with the heating bills so he sent Georgene and I, two mechanics, and a driver and 50 or 60 kids in a ’40s-era bus south into the Yucatan where we could live cheap for a few months before heading back to a less frigid Vermont. That trip is a novel unto itself, but it ended with me paralyzed and inflamed, unable to move from the bed of a truck from which I yelled commandments while George ran the whole complicated, weird show. At Brownsville the doctor told me I had tertiary syphilis and wanted to examine George. They carried me screaming back to the truck, and we headed north. It took the staff at Mary Hitchcock Medical Center at Dartmouth to identify my paralytic, weeping body as a victim of something called Reiter’s Syndrome. They gave me a pill, and the next morning I was, in a word, normal.

It was at Vershire I met Steve Smith, a former Fulbright scholar, motor accident near cripple, Viet Nam vet, a grinder of teeth, and a smoker of Kools. He asked if we wanted to take some kids to Greece for a month-long travel/study program of our devising. We said yes and recruited kids that spring while Steve went to Athens to prepare for our arrival. There were 35 kids and three staff, none of whom had a slight knowledge of what or where or when to do “it.” We barely survived. Georgene was in Europe for the first time and cried like she did the night of our wedding.

And I began my Greek life which I have lived for some 35 summers and a long convalescence from Africa.

Greece: A Nervous Piety

In so many ways Greece is my adopted country, the place where I came to mine much of what is my useful knowledge today. The place is about time, the folly of ambition and greed. A sort of nervous piety exists there — a hangover from when the gods, in mortal shapes, visited to test for generosity, hospitality, and an understanding of one’s place in the world. It is so beautiful that language fails. I’ve climbed Mt. Olympus three or four times, was the unofficial Mayor of Spetses after basing my Magus program on that lovely island in the Saronic Gulf for 10 years. I supplied illegal fishermen to a deaf captain with an octopus boat in the night sea around Skopelos and haggled with monks about how much I had to pay them to have my students work in their vineyards, apiaries, and groves. We crossed the waist and the torso of the country to places like Ionnina where the lake is full of eels and taverna owners love to put light bulbs which burst into incandescence. It was Civil War country. We went to the cliff from which Sappho threw herself. I know Athens better than I know Santa Barbara. I miss her terribly.

At the end of the trip Steve took the kids back to America, and Georgene and I, we headed east, to India.

We were in Jerusalem when Anwar Sadat was shot in Cairo, and the Israelis sealed, as they are still wont to do, the borders until whatever mayhem there was to have, played itself out. We were stuck for a month in that scary, expensive, paranoid city filled with people who deemed the next life to be far more important than this and were willing to prove it a the drop of a burnoose. It was, as ever, full of pilgrims, visiting the Dome of the Rock, caressing the Wailing Wall, or standing on Calvary. All that belief and all those guns. I wanted out of there. I suggested Egypt and Georgene said, I believe, “Okay.”

Dust Storms that Rose like Skyscrapers

We took a bus across the Sinai and the Suez. It was filled with Christians channeling both Testaments. When the bus stopped for water or gas they formed rings, held hands, and sang hymns written on a cold island about this place, this absence of color, ruled by flies and dust storms that rose like skyscrapers then blew through and over. It is where Allah, Jehovah, Yahweh all came from. An angry, jealous desert god who wasn’t ever about to spare the rod. The Sinai answers a lot of questions.

Then, Cairo and its customary madness. We got rooms with a balcony around the corner from Tahrir Square and settled into a routine of exploration and outrageous meals in air conditioned cafés with tall Nubian waiters and menus in French. I interviewed for a school in Maadi outside of the city where the expatriates (hawajaws) lived. It looked like a suburb of Tucson. We decided to go down river, north to the Mediterranean and Alexandria.

Once the indisputable first city of the Western World, Alexandria was rotting from the inside out. The sea air played hell with the paint and the marble and the concrete. The streets were filled with taxis, horse carriages, mad buses, and beggars. We got rooms in what everyone told us was a former brothel close to the Corniche — the long walk beside the sea that ended in the ruins of the Great Library of Alexandria, the burning of which was the single greatest catastrophe of Antiquity and, one could argue, Western Civilization itself.

We took a horse carriage to our interview with George Meloy, headmaster of the Schutz American School in the eastern suburbs. The school was behind tall walls with broken glass on the parapets and two armed guards with rifles. The guards were deaf — their ears filled and caked with wax and dust until one day, six months later, Georgene cleaned them out, and they charged about the compound ululating and shrieking in glee having just regained sound.

George was an affable, somewhat lapsed missionary who had been at the school for 30 years. He interviewed us, showed us around, and told us he had no openings. We gave him the address of our rooms, went out into the street and down to the sea where we caught a tram named Cleopatra. Two nights later we returned from dinner at the Cecil Hotel and there was note under the door saying, “I can always use a good couple, George.”

I became the Middle School Librarian and substitute, and Georgene was the nurse in support of Dr. Aisha, a despotic barrel of a woman who ran the infirmary that treated kids and staff in the compound. There was a full kitchen on campus, and Georgene taught a Home Economics/cooking class that was very popular. We lived at Mamoura Plage, 20 minutes by taxi north on the beach. Our landlord was the Mayor of Cairo. There was an amusement park to our left and a Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise and a mosque at our back. Our front yard was the sea.

DEATH and SEX

After a year, I became a full-time AP Literature and Core English teacher. We moved on campus to apartment above the Infirmary. I had one student in AP English. She was from Yugoslavia and her father a diplomat in Cairo. The first semester was called DEATH and the second SEX of which there is an inexhaustible corpus of literature that could keep us both going until the far-off millennium and then a lot more.

We put on the balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet and read poems and hired a cello player for a Night of Love in the courtyard. I was Santa at Christmas, played golf every Wednesday at the Sporting Club with my buddy Ron Walters where I once won the longest drive competition when I shanked my ball which landed on a trolley that took it all the way to the Mediterranean. Georgene performed miracles regularly which made Dr. Aisha jealous and even crankier than she was constitutionally. There was a muezzin and mosque next door, and the call to prayer became as regular as our own heartbeats.

I took unsuspecting pilgrims from out of town to trace the steps of characters from the Alexandria Quartet by Lawrence Durrell. I would meet them at the airport and drive them to different locales in the novel — writing my own version of the masterpiece as I went along. It was a nice life but then it was summer and we flew to Athens where I attended a job fair in the basement of the Hilton and I met Eddie Tome and was the only one in line to sign up for the International College of West Beirut.

I took the job: English and American Literature before 1948 and counselor for U.S. colleges and universities. The money was fantastic and that, along with mountains of footage and newsprint, should have been a not so subtle warning that something wicked from that way was coming. We flew to the States and, when we left, I didn’t know that I was saying goodbye to my father for the last time.

Beirut

We packed up in Egypt and flew to Portugal to wait for school to open in Beirut. This was before faxes and emails and, in the case of Lebanon, actual phone service. I communicated with the College via a teletype machine and every day received the same news: The airport was closed; the city is not safe; stay where you are; keep in contact.

We moved out of Lisbon to the fishing town of Cas Cais and rented an apartment across the street from a laundry. We ate snails and swam and, even in that cheap country, began to go broke. The College could not wire money. We had already bought plane tickets from Lisbon to Cairo to Beirut.

The last thing my father gave me was a Krugerrand and, when the College telexed the go ahead, I went into the subway station in Lisbon and sold the little gold bar and so paid off the landlord and got us to the airport.

We flew into West Beirut late one night with less than a dollar between us. On the flight were fellahin from Egypt — hired for manual labor — they had never seen a bathroom before, and I came upon them in Cairo splashing and marveling at the seeming impossibility of a urinal. And there was another hawagga (white guy, foreigner, alien) who was a librarian at the American University of Detroit and lived in a lighthouse. I read three days after we landed that he had been kidnapped and murdered, his body found in Sabra or Chatilla along with so many others. A cab took us through the lunar landscape into the heart of Ras (the Head) Beirut where he dropped us at the mansion of the President of the College who answered the door in a galabaya or kaftan, paid the driver, and told us “to buy Stolichnaya while we can.” He sent for a small boy who found a man who took us to our new home in an apartment at the intersection of Sadat and Rue Bliss.

We were almost in the basement but had one window that looked out onto the street. There were heavy bars on all the windows and a double- or triple-locked door. There were four rooms. It was a bunker. But now it was home.

Two days later they blew up the Marine barracks by the airport. Our window to the street bowed under the blast. You couldn’t hear anything. The smoke was spectacular. It was the worst assault on America until 9/11. Reagan began filling the bay with every sort of fantastic death machine. There were flyovers and flybys. There was celebratory bombing in the Bekaa, unrest in the Palestinian camps where the Israelis (Begin and the Jets) had so recently slaughtered hundreds. All night there was gunfire. The news was like a wicked weather report with forecasts of “incoming in Ras Beirut, shelling along the border, small arms exchanges in Sabra and Chatilla.” We were rattled, afraid, and curious.

Inexplicably, school began. It took a half hour of security to get from the front gate to my classroom. The place was ringed by serious boys with serious weapons. There were tanks, armed personnel carriers, and jeeps packed with men bearing AK 47s or MPGs. There was a double feature playing at a local cinema which was showing Deep Throat and Rambo — smut and violence, violence and smut. The money changers were changing, there was rock and roll in the streets, and everyone was smoking and arguing and then laying down mats when the muezzin made his call to prayer. There was cordite in the air and the cackle of gunfire far and near.

My classroom was above it all, shaded by elms with my magisterial desk in front of the orderly rows where my students, dressed in Dior, Versace, and houses of fashion I cannot imagine or name, sat expectant, pens poised, ready to learn, ready to forget, anxious for the timelessness and escape literature affords, wanting to be in Paris or Berkeley, anywhere but here where one of them died each week I taught. I was lecturing on the geography of Long Island in order to make some sense of The Great Gatsby when a small boy came with a note telling me to come to the office. I had a phone call. My brothers told me that my father had died. I walked home in my new suit, doubly lost, and Georgene and I mourned.

The String Is Wound Way Too Tight

It was impossible to get out of the neighborhood, let alone the country. A one-eyed man said he could” slip” me into a sling beneath his semi and get me to Aleppo and from there to Damascus. It was dicey at best and I didn’t think my mother needed anyone else to mourn, so we holed up for a day listening to incoming rockets and watching columns of smoke rise up all over the city through our one barred window into the street. There were sirens and screams and the sound of crying children and mothers shushing throughout the building. Everyone on the street wanted to get off the street and so were scurrying, looking up and down and all around like impalas in a particularly vulnerable part of the veldt. And Reagan’s warships were multiplying in the harbor. There was an air of intolerability in the air as in “this can’t last, the string is wound way too tight” or as Macbeth’s Weird Sisters might say, “By the clicking of my thumbs / something wicked this way comes.”

My students were of the elite of Lebanon. They were rich, beautiful, impeccably dressed, and hungry to learn about the world beyond the Levant. They called me Oostez or Maestro and brought me tea and questions about books and poems, Hollywood and Manhattan. It was their dream to go where they didn’t need bodyguards and where one of their classmates, at least, didn’t die each week. Taking roll was heart stopping. In faculty meetings the names of the dead teachers were read at the beginning of each session. Almost every class found us all under a desk, the classroom walls reverberating and the cordite creeping. They wanted back into the lesson immediately and seamlessly. There was no need to comment on the mayhem; it was like rain in Seattle.

I worked, after curfew, as a “stringer” for the Daily Star, the only English, nonpartisan, religiously unaffiliated newspaper in Beirut. I’d come home alleywise very late watching out for militias or the rats that were as fat and free as sailors on leave. The sound of gunfire was almost a constant, a back beat, the throbbing heart of a dying city.

This went on until mid-winter. Georgene was working as a triage nurse at the American University of Beirut hospital. We went skiing beneath the Cedars of Lebanon, went to feasts in the Bekaa; I was ordained in my kitchen as a Reverend of the Universal Life Church and performed my first wedding in the village of Byblos were books were born. Then one day, sitting on my couch correcting essays, I looked through the window at a young woman who was picking up her daughter and running. Her eyes were wide with fear and then she was gone and the Battle for West Beirut began.

I didn’t leave the apartment for many days. Georgene was at the hospital. The shells never stopped flying and falling. They were coming off the USS New Jersey in the harbor, shells the “size of Volkswagens” and other shells were just being lobbed into our neighborhood. Next to classroom was where they parked the school buses that rode, heavily armed to and from the suburbs every school day. There was a direct hit by some infernal death device, and 30 buses exploded and burned. It was two blocks away, and I couldn’t hear it as my own neighborhood was cacophonic with disaster and random astonishing noise. I spent a day and a night rolled up in a mattress like a hot dog in a bun in the soothing darkness of my bathtub.

My students came and found me. There was a car hanging from the balcony off the fourth floor; the path to the apartment was rubble and a tricky climb. The barber shop next door was, simply, gone. The electrical system of Ras Beirut was a pasta of severed wires sputtering in pools left by a storm that must have stormed. Georgene came home. She hadn’t slept for days. She had been “ankle deep in blood,” making awful decisions in response to impossible demands.

We filled a backpack, I had my copy of the Collected Works of William Shakespeare, and we headed to the embassy past where my school had been last week. We spent three days in the basement of the Mayflower Hotel — the 30 or so Americans that were left. Missionaries, spies, teachers, and journalists huddled in the dark, raiding the wine cellar and existing on forays into the hotel kitchen. All the networks came in by helicopter, interviewed us and, incredibly, set out to leave. They weren’t taking us with them. I started a chant, “Vampires, Vampires, Vampires.” They slunk away with their cameras and fuzzy microphones to safety somewhere while we waited for the fire and the end.

We heard it from the BBC. All foreigners were to make their way to the corniche beneath the redoubt of the French Embassy. There we were to wait for the helicopters that finally came. My tea boy revealed himself to be of the Mujagadeen and he showed us where to hide from the sniper fire coming out of the bushes while we were milling about on what was left of the great promenade. When the helicopters came we boarded, and I watched as one of my students was shot in the neck seconds before ladder’s end. The amazing ships flew us onto the wee deck of the USS Montauk, a destroyer with a banner that read, WELCOME TO THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA. Dinner would be served. The movie for the night was Poltergeist. We stood on the deck, said goodbye to Beirut, and then watched it burn.

We sailed for Cyprus and had too many adventures to tell here. I sat at the end of the dock of the bay with Dr. Jeremy Sykes, the director of the Upper Faculty, and we discussed my future. I was broke, out of a job, and owned a few clothes and a big book. He said, “Have you thought about Harvard?” Mine was a hearty laugh but then all that began.

‘Not the Admissions Mistake’

We made our way to Boston where we got a strange apartment on Newbury Street. Jeremy muscled me through admissions at Harvard where he had got his doctorate some years before. They needed me to take a test and write a personal essay which I did and soon received a simple letter welcoming me to Harvard and assuring me I “was not the Admissions mistake.” Georgene got a job in the Projects; we found an apartment in the ghetto, a third floor pad above an Ethiopian church with a backdoor entrance — hence the sign on our communal front door admonished the faithful and the curious to “Enter All Saints From the Rear.” It was on the Orange line and blew me every day into the rarified air of Cambridge from the blood, sweat, and tears of urban blight. On our street were a couple of blues clubs, the world headquarters of the Christian Science Church, and an Irish bar called Foley’s where I wrote all my papers and plotted against the vast establishment of which I was now, evidently, a part.

I had met Noel Ignatiev at Orientation, and we became fast friends fast. He was later to be named by Rolling Stone as the “Most Dangerous Man in America.” We were both granted work-study fellowships which, in our case, meant bringing pizza and beer to the brightly lit office of a local anarchist newsletter. We found out the 10 centime coins from France worked in the subway stiles, and we got thousands of them to use and distribute with the sole intent of putting any kind of pressure on all the Harvard graduates who were now oppressing everyone else and, as we saw it, enjoying the fruits of their elitism and avarice. It was all really very harmless but a diversion from the classroom that was yielding very little. I got an “A” on my first academic paper in years and never really took much very seriously after that. Georgene was doing the real work of the family; I was merely recycling academic tripe that really never went anywhere. I was itching like crazy for the road.

Georgene worked the magic she works, and we were granted interviews with the International Rescue Committee in Manhattan just around the corner from the library and its lions. I went back, graduated (with my mother and nephew Jesse in attendance) and contemplated Africa where someone always needs rescuing.

The Worst Place in the World

I was named Administrative Director of the Tawawa refugee camp in the Eastern Region of the Sudan. Georgene was to work in the natal clinic with the venerable and intimidating Dr. Asnakash and the bumbling Dr. Yusef . We were to live in the Sudanese city, Gedaref, described by my predecessor as “the worst place in the world”. But first we flew First Class on Lufthansa to Zurich (all costs donated by someone or something), where we ate dinner beneath an original Manet, and then the night flight to Khartoum.

Khartoum is famous for a lot of things like massacres, the final gasp of empires, starvation, Nile blindness, corruption, and dust. There was a post-apocalyptic feel to the place. Like The Bomb had fallen and left only animated skeletons or arrogant fat cats behind high walls with private militias. The Zoo was the saddest place I had ever seen but that distinction was soon to be outpaced by the tubercular or the cholera ghosts in their metal, final beds and the bloated children with filmy eyes and thousand mile stares.

We slept in a barracks in cots while our orders were cut and transport was arranged for the journey due east almost into Ethiopia. We swam in the American Club pool and ate hamburgers and drank Cokes with ice under green trees and bougainvillea. Turbaned Sudanese waiters swished about in their galabayas noiselessly, obsequious and desperate for tips. There could not have been a more inappropriate introduction to Africa and what lay ahead in Tawawa and the Rural Settlements of Hawata, Mawfaza, Abu Rakam (“the Father of the Birds”), and Wad Hawad.

On the long road east a nurse from San Francisco told us all about a “new disease” she didn’t, no one did yet, have the vocabulary for but the Africans had been calling the slimming disease and we were going to call, one day fairly soon, AIDS.

Gedaref was built of low buildings composed of camel shit, mud, and concrete. There were decayed, long since stripped, remnants of British rule, rusted tracks, and a European electrical system which went down one night shortly after our arrival and simply never came on again. We lived for close to a year by candlelight and an occasion generator jolt which became increasingly unpopular as it made us a very attractive target for the teeming, undernourished populace who were always trolling for any sort of break.

The heat was astonishing. The dust was the atmosphere. There was nothing green for miles. Everyone was poor. Many were sick, crippled, and shaken by long and short lives of desperation, disappointment, and hunger. And that was before we got to the camps.

Tawawa

Tawawa, we were told in New York, had some thirty to thirty five thousand refugees living it on any given day dependent on the weather or the level of political ferocity in the Horn of Africa. They were Ethiopians, Christians, animists, believers in Jesus and all the saints as well as witches and all their powers. There were an estimated four to five thousand prostitutes and the slimming disease was rampant. There were snakes. The shitting fields were west of the camp and that’s where everyone went twice a day. The excrement would dry in the heat and become part of the atmosphere that you had no choice but to breathe. Water came in by donkey, food by trucks — sacks of wheat and corn with the words A Gift From The People Of The United States embroidered across the mouths of the bags. We ate foul — a bean paste — and an occasional lucky egg in “restaurants” made of sticks — recubas — and thatched roofs to keep out the sun that seemed far too close to the world. There was murder, the weapon of choice being the honed parts of abandoned Aid vehicles. All day people were dying and being born. Funeral ululations and jubilant birth celebrations fought for dominion. I hired some Dinkas from deep in the Sahara to dig a well and at night they would drink tedge, the local brew, and dance a dance that was jumping, projecting the seven-and-half-foot frames higher and higher into the firelight. There were fires that erased great swathes of the camp; the camel shit and thatch round tucals were excellent fodder for flames. A prostitute died in my arms from snake bite while the Sudanese doctor looked on and finished his tea before breaking out an antidote. I drove a boy to the hospital to have his perfectly healthy hand amputated to give notice to all the world he was a thief. Georgene went into a Sudanese prison with Dr. Yusef and attended to the mothers and infants. I planted a hundred trees and hired twenty guards to keep them from those starved for fuel or color. I paid a witch to save a little girl. I petitioned a Swedish aid group for a fire truck but they sent me a million condoms for which I had to build a sort of Quonset hut and hire a guard. I decided, like Mengele, who could come into the camp and who was healthy enough to continue the long walk through the aid archipelago to Khartoum. We went to the Ethiopian border to Wad Medni which was, at the time, the largest refugee camp in the world. There was a river there and a church whose principle deity was Michael Jackson. There was electricity which by then had become a mostly forgotten marvel. I lectured the elders. My translator smuggled pork and gin from Addis Ababa in slings beneath the carriage of semis filled with gifts from The People of the United States of America. We had cholera but couldn’t call it that or let it be known that there was disease for which we had no name. I caught malaria, bad air, and they sent us to Kenya for three weeks to recuperate.

North of Nairobi was the former coffee plantation of Karen Blixen and where much of her novel/memoir Out of Africa takes place. It was then the International School of Nairobi, and we went to interview. It could not have gone better. I taught a class on two poems the Head of English gave me, Georgene interviewed with Infirmary personnel, and the Headmaster gave us jobs the pay for which was breathtaking and residences on the estate, gave us some names to contact, and put us on a train to Mombasa. We were set, it appeared, for 10 years or more in Kenya. We were back at Tawawa when the telex came through from Khartoum that the Headmaster I knew in Nairobi had been replaced and his successor wanted to bring “in his own team.” I was inconsolably sad for days. I sent out 100 resumes. We went to Athens and then to the Peace House where we lived in a villa that was built by one of the men on the Enola Gay. I read through his library and his copy of Crime and Punishment with notations and annotations. I should have stolen it but instead went back to Athens.

At the front desk of the Aphrodite Hotel in the Plaka I got a call from Mr. Joe Houston Walker, headmaster, who offered me a job teaching, English, History, and Geography at the International School of Las Palmas on Gran Canaria, Spain. We could still see Africa.

Gran Canaria, Spain

The school was built in two days 20 years before by NASA. They blew up huge balloons and then poured concrete over them. The concrete hardened and they popped the bubbles and then there was an astronomical outpost in a place where the stars and planets were very close. I was working in another room without corners. I became High School Principal; Georgene broke her arm coaching basketball. She had Spanish lessons with a blind man. Steven and Brenda came out for a memorable visit. We bought a feeble, wholly unpredictable car which, at the end of our two year stint, got us to the airport where we left it, keys in the ignition.

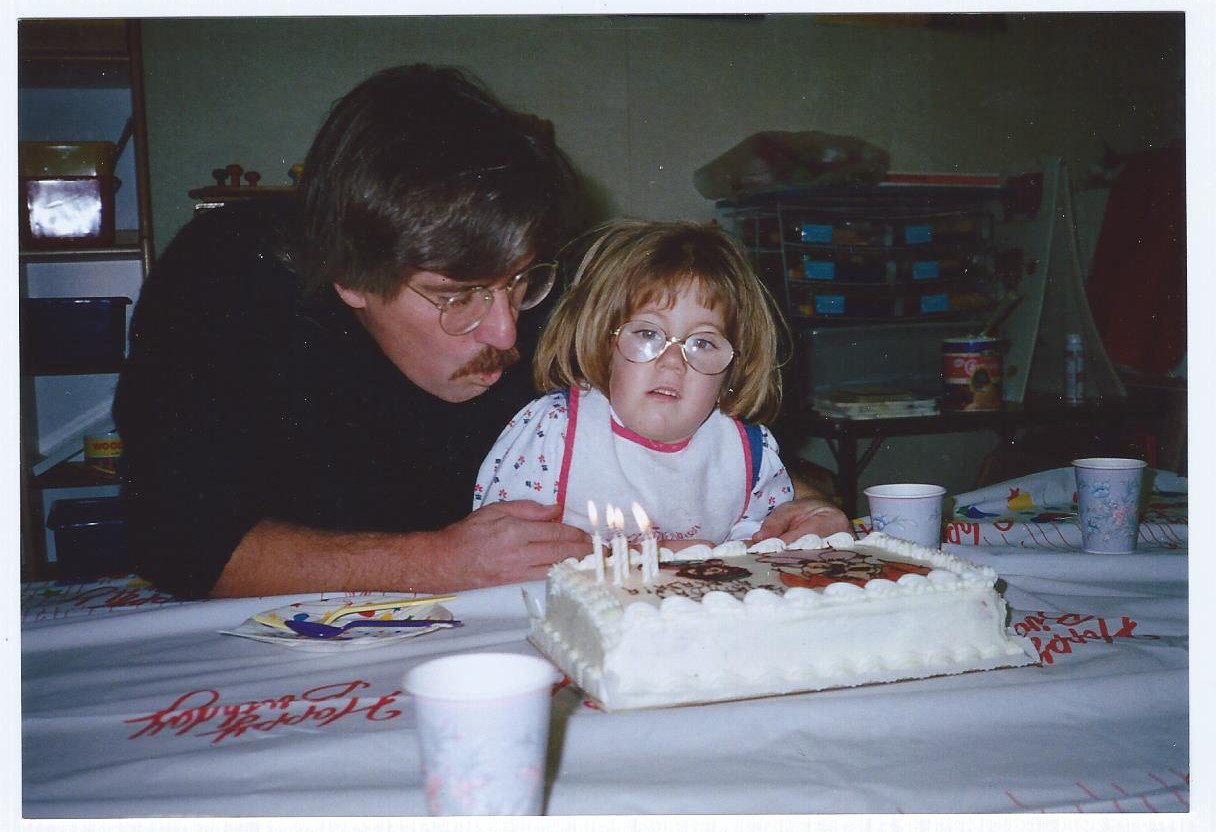

We lived in a 200-year-old house with three or four verandas, a gardener, and a rather slow dog named Einstein. Steph came out to live. Part way through the second school year at a place we called Paco’s Pork on the road to our village San Lorenzo, Georgene told me she was pregnant, and then the rest of our lives began.

Alexandria Warrington Lowe was born in December in Las Palmas. She was weak and did not take to the breast. We weighed her daily in a pharmacy in the next village over, and Georgene pumped and pumped. She was the Bun shortly out of the oven when Carnaval and torrential rains came to the island along with my mother who ministered, coached, soothed, and loved. We flew to Orange County, and Russell and Kathy helped us navigate the children’s health system which, finally, offered little information or advice. We flew back to Spain and collected our material lives, said a lot of Adioses, and headed for America.

Dunn School

We stayed at Uncle Sid and Aunt Mar’s house in Pauma Valley and tried to figure what to do. We took a road trip (whose car was that?), and while driving past Santa Barbara, I suggested we go to the valley where I went to school and campus I had not seen since Commencement in 1970.We met with Steve Loy who was then Headmaster, and he offered me a job in the English Department. We are still there in a delightful little house that Georgene made. We have been around the world, raised a unique and astonishing girl, grown gray and somehow venerable. Georgene is a major player in the lives of a great many people who would have no one else to help them if she weren’t around. Alex now lives in her house that Uncle Sid bought in Santa Maria where she is the roommate of two young women and the focus of 24-hour-a-day staff. She comes home with her dog Holden on weekends.

So, my story is almost over. Georgene’s and that Bun’s are many more years long. I will miss a lot. I have been loved and have loved not too many but certainly enough. Those who I have loved know who they are, and if they do not, this I regret.

Into the “undiscovered country from whose bourne no traveler returns” as Hamlet said, where “all the rest is silence.”

Kalispera, Ralph

Related Stories

Wine on Ice Part One, at Joe’s Cafe

More of Ralph’s stories can be found here.