Tosh Clements: From Graffiti to Art Show

S.B. Native Shows Paintings at Breakfast Culture Café

Graffiti is a school of art without tuition or degree, but it’s complete with lessons in composition, size, color, and, importantly, “line.” When a painter develops his line or stroke in the school of graffiti, it stays with him or her as they develop a style and presentation beyond the sides of buildings and train tracks, transitioning into more formal gallery settings.

Tosh Clements, born and raised in Santa Barbara, is a longtime photographer and professional cyclist who grew up influenced by straight-edge punk and graffiti culture. His bright, iconic, infectious new work is showing at Breakfast Culture Club (711 Chapala St.), the café and art gallery.

An artist’s stroke says everything about their work. That line is like a genetic marker, a fingerprint, a blood test, indicating where the artist is from and where he or she may go.

Clements is self-taught and self-educated; in fact, after the first two hours of high school, he walked out and never returned. Clements has a great deal of sensitivity about the issues around public graffiti, especially in a pristine town like Santa Barbara, but he doesn’t hesitate to admit how much he learned from those early days. “There are basics about spray-painting on buildings a graffiti artist learns,” Tosh said. “Big is good; your style must be instantly recognizable. You do it to get a reaction. But it’s anonymous.”

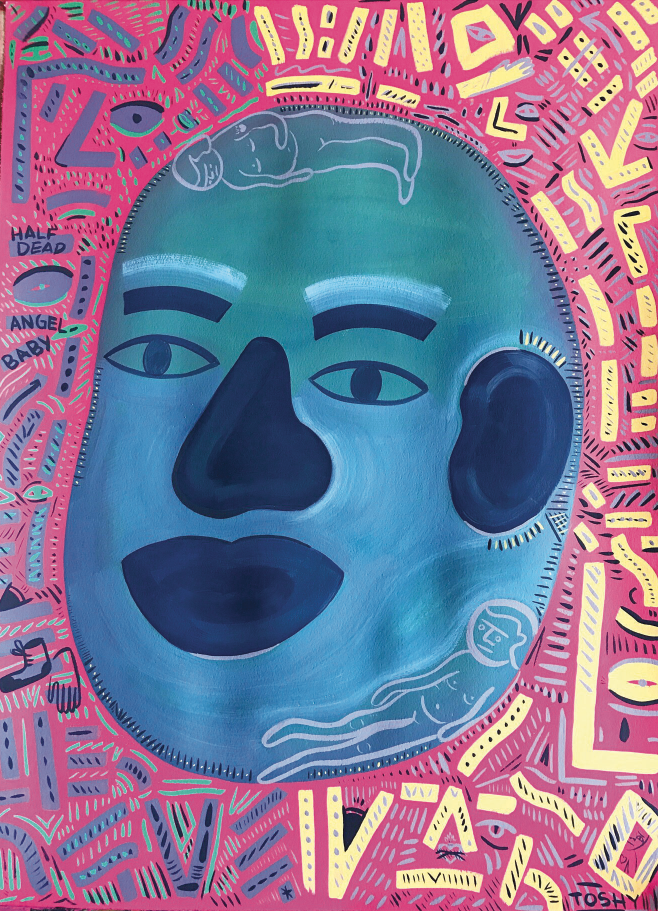

Clements is no longer concerned about being anonymous. His new paintings include red-and-white prints of floating heads, abstract color studies, and larger, deeper paintings with an eye toward cyclical issues of life, death, and rebirth. Each of the larger paintings feature a central human “head” usually in profile, inundated by thoughts, facts, and worries as if an entire life were flashing by.

In “Modern World,” the central face is framed in profile, composed of fragments, a pastiche of color and shape, put together like a jigsaw puzzle. Other faces float in and around the larger profile — a baby, a boy in tennis shoes, the words “death bed” — creating a churn of imagery unified by the broken calligraphy of Clements’s ever-present “line,” stabs of paint that echo and unify the composition.

Another painting, “Bored Teenagers,” whose title echoes the Nirvana song “Smells like Teen Spirit,” centers around a frontal blue-black head floating in an orange-red background. Looking simultaneously like a Buddha, an Easter Island totem, and a skinhead, the image summons a universal sense of culture. The words “angel baby,” “half dead,” and “not again” are painted among the ripples of slashes and dots. It stands as one of the most accomplished of the large works.

Recognizable and anonymous are the contradictions of graffiti art, and they provide a backdrop for these works. Clements’s painting owes a great debt to the trio of graffiti kings from the ’80s: Basquiat, Haring, and Scharf, all of whom started as taggers and made stunning transitions to the world of art.

A more direct influence closer to home is the world of Barry McGee and Kate Kilgallen from the Bay Area whose strange symbiotic works simultaneously explored representational images without losing their graffiti heritage.

Deadpan humor threads through all of Clements’s work, especially his ephemeral Post-it drawings, filled with comic panels, iconic images, and words pasted to the walls of the gallery like modern hieroglyphics.

Who knows where an artist’s line will take them? Clements has just returned from a tour of European galleries sure to inform his art, which is already a new and present development in the growing world of contemporary, alternative voices in Santa Barbara art.