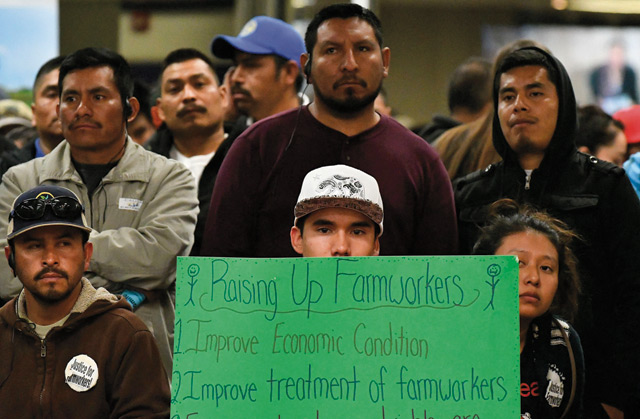

The Santa Maria Betteravia Government Center Hearing Room was so packed Monday evening for a town hall meeting about farmworkers’ harsh conditions that county firefighters opened the accordion doors to allow people to spill into the foyer, many followed by bustling small children.

For the better part of the year, advocates with CAUSE (Central Coast Alliance United for a Sustainable Economy) pressed the county supervisors — specifically board chair Peter Adam, who co-owns a giant family farm — to host a hearing at which farmworkers could speak openly about the struggles they endure every day. In October, county supervisors Janet Wolf and Salud Carbajal finally agreed.

At a time when the election of Donald Trump has instilled fear about deportation in immigrant communities, the event functioned in part as a space for grievances to come to light. Of the 17,000 farmworkers in North County, CAUSE believes 72 percent are undocumented. Monday’s meeting offered translations in Spanish and Mixtec.

In addition, representatives with oversight agencies, including the state Labor Commissioner, Cal/OSHA, and the District Attorney’s Office, explained the appropriate course to file formal labor complaints. Many agents, namely John Savrnoch, chief deputy district attorney, emphatically told the audience, “Your immigration status is of absolutely no concern to us.”

Several fieldworkers spoke about the dangers of pesticides, particularly for pregnant women, as well as wage theft and inadequate rest breaks. The number of pesticide-related complaints in the county filed with state regulators has gradually increased in the last decade. In 2013, the most recent year for which data is available, 47 fieldworkers reported nausea, headaches, and burning eyes, among other symptoms. In 2014, a state public health report rated Santa Barbara 13th of 58 counties in terms of high pesticide use.

Hortencia Hernandez, who works with Catholic Worker in Guadalupe, said she has known 10 women under the age of 40 who died of cancer after working in the fields. “I raise the question, ‘Why?’” she said. “And I think it is for our government leaders to figure out.”

Growers, however, have long argued that the state’s legal protections are some of the toughest in the country, and they continue to strengthen. For instance, Governor Jerry Brown signed a bill to gradually implement greater overtime pay for farmworkers, which the ag industry strongly opposed. Claire Wineman, head of the Grower-Shipper Association, said at the forum that a “multitude of protections” already exist, including at the federal level.

Last year, four fieldworkers sued cooling facility Apio and its contractor Pacific Harvest for intentional employer misconduct. They alleged their bosses forced them to “clock out” while walking from one part of the facility to another. They also claimed they were paid less than minimum wage without compulsory overtime. Labor attorney Stan Mallison, who is rooted in the Central Valley, explained the case was filed under the Private Attorneys General Act, or PAGA, which allows plaintiffs to stand “in the shoes” of the state to pursue labor investigations. Early next year, Mallison said, the case is scheduled to go before a private mediator. Apio did not return calls for comment.

Juan Cervantes, an organizer with United Food & Commercial Workers, implored farmworkers to follow the lead of the Apio workers and speak up. “Agencies can’t do nothing if they don’t have a client,” he said.

The real remedy, some advocates say, would be to unionize fieldworkers in Santa Barbara County. Earlier this year, two attempts to form a union at Apio failed, according to Antonio Rivera, a former organizer. He said Apio hired a consultant to dissuade workers from voting for the union. Two elections failed, he said, one by about 50 votes and another by more than 100. “The workers need to learn more about their rights,” he added.

In the meantime, Hazel Davalos, a director with CAUSE, hopes county supervisors will create an ombudsman position to connect farmworkers to the aforementioned state agencies. Davalos explained “the laws on the books aren’t necessarily the same laws on the field.” In addition, language barriers and other reasons often prevent farmworkers from connecting with available resources.

It is worth noting that some progress has been made. For instance, the county Agriculture Advisory Committee has formed a labor subcommittee to better involve laborers in these discussions. And they want to be involved, as Davalos pointed out at the forum: “Great turnout,” she emphasized.