In truth, I was never keen to have children. Motherhood, after all, would have dampened my fevered ambitions, and kids, of course, would have ended my own lifelong childhood.

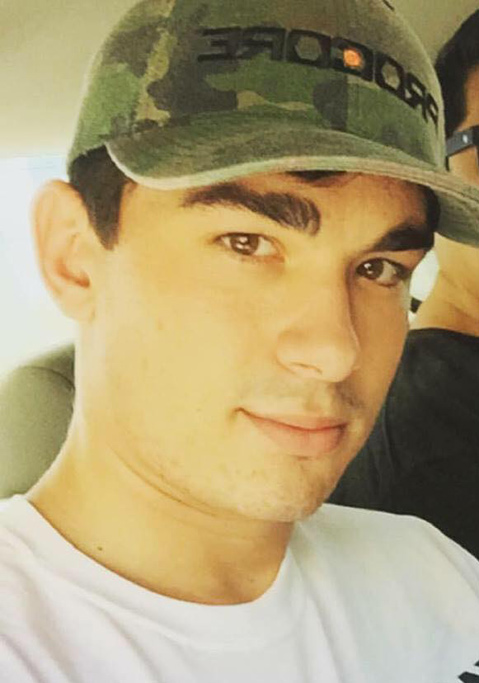

Then I met Ripkyn, age 14 — skinny, slouched, with shaggy dark hair and majestically broad eyebrows lurching above black horn-rimmed eyeglasses and teenage zits. Maybe it was his ferret mind ever on the hunt that snared me or that hungry heart of his that sponged up the world.

I first met Ripkyn at the Santa Barbara Vedanta Temple where the nuns — being close to several family members — offered him an occasional second home. They had discerned in Ripkyn a keen spiritual hunger — one typically found in the elderly, not pubescent teenagers.

When he was 15, Ripkyn lost his father — a dazzling guy-about-town who died too soon and too young. Alternately brooding, grieving, and hilarious, Ripkyn liked hanging around our house, tending to our beagle Lupe, chowing down on endless almond butter and jelly sandwiches, and talking books, drugs, recovery, politics, and booze.

Ripkyn, it turned out, was my dream kid. When I gave him James Joyce’s Dubliners, he inhaled it in two days. And how he was dazzled by Milton’s glorious invocation in Paradise Lost — “What in me is dark / Illumine …” In July, I sent him Richard Ellman’s biography of Joyce, which he promptly devoured.

Ripkyn came from good Santa Barbara stock — a family, as he liked to regale us, chockablock with saints, smarty-pants, surfers, and drunks — all exceptionally good looking. He was a natural writer and storyteller with a trove of tales. There was the story of the relative who hustled drugs out of Southeast Asia under diplomatic cover, the king surfer-dude who left for Mexico, the marine biologist great-grandfather, and, the coup de grâce, the geriatric meth dealer relation (until he sobered up). When I asked him to compose a genealogy, he tracked relatives going back more than a century, noting birth and death dates — an exercise that turned into a meditation on the unforgiving beast of alcoholism.

At 16, Ripkyn went to India to study at Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda University outside of Kolkata for six months. He was given the spiritual name Kamal, meaning “lotus,” engendering plenty of ribbing from the Vedanta nuns, who dubbed him Little Lotus.

A revered monk, the late Swami Tathagatananda wrote Ripkyn’s hard-working, single mother when he left the States: “I am almost 35 years in this country … but your son is special for his purity of character and spiritual longing which appeared at a very young age. I cannot recall that I have seen such a boy in the U.S. Even in India, these sorts of boys are very rare.” Once, he asked Ripkyn/Kamal to recite a passage from the Bhagavad Gita. To his astonishment, Ripkyn, from memory, “chanted the verses in English for about 10 minutes. He could have continued for even one half hour … In these days of rampant materialism, Kamal is one in a billion.”

Within a few months of living in Kolkata, Ripkyn was reasonably proficient in both Sanskrit and Bengali. And he was clean and sober — until he wasn’t.

Back home in Santa Barbara, he hit another bottom. Then he dove deeply into recovery, attending AA meetings daily, nailing a 3.9 GPA at City College, holding down a job, dating an old friend, and staying with us from time to time.

At 17, he wrote an essay for his English class titled “Epiphanies of Powerlessness,” confessing, “I have personally experienced the force of powerlessness in all its beauty and paradox in my own life … I myself felt for most of my life that I was in control of my situation, even as — at the tender age of 13 — I spiraled into addiction and near madness. Even after my father’s death and my subsequent recognition of the peril I faced as a fellow alcoholic and addict, I continued to make bets … It was not until I received my revelation, thorough the medium of Alcoholics Anonymous, that I watched my life transform miraculously.” Epiphanies, he stressed, “require both insight and revelation, a conscious effort and an experience of grace.”

I have met more than my share of hope-to-die-addicts, and Ripkyn rivaled all in appetite, or, as he put it, his quest for “the ecstatic.” But Ripkyn had a quality rare among addicts, for whom it is an article of faith, even a cliché, that moving lips are lying ones. It’s the DNA of addiction — but Ripkyn invariably told the truth — to himself and others. “I’m going on a run,” a binge, he would tell his pal Christian, who like so many in Santa Barbara, credits his life and recovery to the rescue efforts of Ripkyn. It was Ripkyn’s goodness, in the end, that made you swoon. In his last letter to his mother, he wrote, “When I drink and use, I do crazy, bad stuff. It’s not me … Thank you, thank you, beautiful mom. I love you and I’ll see you and look out from above.”

Ripkyn was a truth teller with a yearning that seemed no less than that of Augustine — even amid the battle fatigue and demoralization of relapse.

I had told Ripkyn that I would help him write his memoir — his saga of survival. That was the plan. In early August, he called a few times and wrote, “Thanks again for not giving up on me. I will try my best to do the same.” I could hear his cryptic laugh punctuating that last clause.

In his essay on epiphanies, Ripkyn wrote that “the source of beauty is awe … And the more we are filled with this awe … the more we can experience the unfathomable mystery and uncompromising reality of the world and the more we may enjoy peace and the power that comes after powerlessness.”

Oh, how we will miss him so.

A memorial will be held at Vedanta Temple (927 Ladera Ln., Montecito) on Saturday, September 17, at 11 a.m.