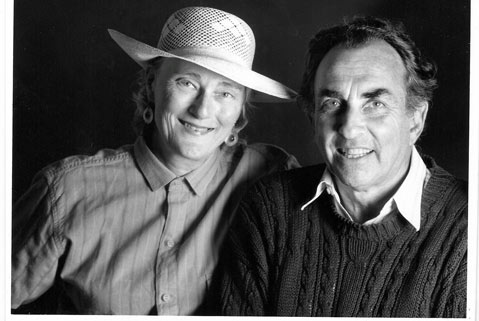

Few things illustrate the unforeseeable reach of the butterfly effect as powerfully as the 20 years Bob Klausner spent in Santa Barbara, during which time he emerged as the city’s most influential power broker and civic activist since the days of T.M. Storke and Pearl Chase. Back in 1972, Klausner was a successful business executive living in New York City, leading a textile company and happily married with three kids. But one Saturday afternoon, as Klausner was pulling into a parking spot near his office, another driver blatantly poached it. “That was the last straw,” recalled his youngest daughter, Kathy. Back at home, Klausner announced to his family: “No more,” and soon they were heading west to California. The plan was to settle in either Santa Barbara or Atherton. Santa Barbara won — as local folklore has it — after Klausner met a young arts advocate, the photographer Tom Moore, in a chance encounter. If Santa Barbara could attract such creativity as Moore’s, Klausner concluded, it had to be the place. For Bob Klausner, it marked the beginning of a passionate romance between man and city that lasted until the day he died.

Were it not for such seemingly random events, the political history of Santa Barbara from 1973-1993 would have been profoundly different. It is almost impossible to exaggerate Klausner’s impact in that time span. Arriving in the turbulent period following the 1969 oil spill, Klausner fused his business acumen, high-beam intelligence, and political genius with Santa Barbara’s burgeoning environmental movement. Were it not for Klausner, the city’s first successful recycling program would never have happened. Without the revenues from that enterprise, the Community Environmental Council (CEC) — now celebrating its 46th year in operation — would not have survived. He fought against megaresorts and for growth management plans that sought — however unsuccessfully — to balance the creation of new jobs with the city’s limited housing supply.

Klausner never operated as a lone wolf. He collaborated creatively with the alphabet soup of environmental and political organizations — some of which he did not always see eye to eye with — in pursuit of mutual goals. “If there was no organization to do it, he would create one,” said Harvey Molotch, retired UCSB sociologist and author of “The City as a Growth Machine,” the Magna Carta of Santa Barbara’s slowgrowth movement of the 1970s.

In person, Klausner could be intimidating and overwhelming. But he could also be warm, curious, and generous, both with money and insight. For years, he offered such wise advice to Marianne Partridge, the editor of this paper, that she always referred to him as her rabbi. And he helped support an earlier manifestation of The Santa Barbara Independent, the News & Review, by offering low rent in two of his real estate properties.

When the oil industry set its sights on Santa Barbara’s abundant offshore reserves in the early 1980s, Klausner played a crucial role in limiting onshore oil-processing facilities. He helped bring an end to oil tankers in the channel, forcing oil companies to transport their product by pipeline instead. Klausner was on the frontlines of efforts to impose more stringent onshore air-quality standards because of the pollution generated by offshore oil platforms. In response, Exxon’s representative famously told Klausner and the environmental community to “stick it in their ear” during a county supervisors meeting. Almost as famously, that Exxon spokesperson swiftly found himself relocated to Alaska. The tough air-quality standards, however, stuck.

First and foremost, Klausner was a businessman. In 1973, he bought a partnership interest in the seven-story Balboa Building at 735 State Street. At the time, Santa Barbara had no department stores downtown, so when City Hall began talking about revitalizing State Street, Klausner jumped on the bandwagon, advocating for what would become Paseo Nuevo, then one of the few open-air malls in the country. The deal required that the developer devote space to an art gallery (now the Museum of Contemporary Art) and a live theater space (now Center Stage Theater).

Klausner practiced politics with a lowercase “p,” indifferent to party affiliations, at least in the conduct of local affairs. It was all about getting things done — which meant knowing whom to talk to. If a supervisor’s mind needed to be changed, Klausner would enlist that supervisor’s best friends to the cause. Klausner was also a powerful listener. He talked to everyone. “He’d mine my brain with a pick and shovel,” remembered Dave Davis, former head of CEC and onetime City Hall planning czar. With Klausner, political disagreement rarely got personal. “We didn’t see eye to eye on a lot of things,” recalled developer Jerry Beaver, then the hobgoblin of choice for environmental activists. “But we agreed to disagree. He was a good adversary and a good guy.”

Over time, critics began calling him the “Sixth Supervisor.” He didn’t much care for the label, but it caught on. If elected figures such as Naomi Schwartz, Bill Wallace, Tom Rogers, and Hal Conklin were the bricks of Santa Barbara’s slowgrowth movement, then Klausner was the mortar binding them together. Klausner recruited and nurtured candidates, decided when they would run and for what office, bankrolled their campaigns, conjured strategies, defined agendas, and held elected officials to their word once voted into office.

Klausner, however, was by no means omnipotent. For years he railed about the structural dysfunction of county government and pushed for organizational changes that he insisted would make it more efficient. Those ideas suffered long, slow deaths, and Klausner agonized as they did. His eyes could explode off his face in such battles, his bushy black brows rising like smoke. Paul Relis, founder of the CEC, described Klausner as “the most linear thinker I ever knew. He had an absolute faith in the rational. He believed if he could talk directly to people, they’d have to acknowledge the reason of his arguments.”

When things worked out that way, Klausner was stunningly effective. But, Relis believed, Klausner could never grasp the extent to which nonrational considerations influenced political outcomes. In such moments, Klausner would be rendered breathless with incredulity. Perhaps the most dramatic example of that was in 1990, when he joined the forces fighting against the ballot initiative to hook Santa Barbara into the state water system. Santa Barbara was then in the throes of a devastating drought, and the Miracle March rains of 1991 were still months away. State water won.

Bob Klausner grew up in Jersey City, New Jersey — the older of two sons — to David and Mickey Klausner, both first-generation Jewish immigrants from what, in the late 19th century, was Russia. Klausner’s grandfather on his mother’s side, Morris Miller, fled Lithuania in 1888, escaping after he had been arrested for dodging the draft — military service for Jews in the Czar’s army was all but a death sentence. He made it to New York, where he eventually went into real estate.

By the time Klausner’s mother, Mickey Miller, was born, the family was more than comfortably middle class. Mickey was smart, vivacious, fashionable, bossy, opinionated, and known to nurse grudges. She graduated from Barnard College and in 1925 married David Klausner, a Columbia-educated lawyer from Jersey City. Bob Klausner was born in 1926; his younger brother, Bill, came three years later. As a child, Klausner was smart and athletic. Though not religious, the family was involved in Jewish social organizations. In high school, Klausner was one of only a few Jews, and he reported being bullied because of it. His mother was quite strict, and when he got in a fight, she punished him severely. It was the live-in housekeeper, Isabelle Glover, to whom Klausner looked for emotional sustenance and who instilled in him a sense of community responsibility.

Klausner attended Yale during World War II, graduating as part of an accelerated naval officers training program. He spent two years in the U.S. Navy, attended Columbia to get an MBA, and dropped out after one year to work for Macy’s. Economics he would later dismiss as “voodoo science.” After figuring out a puzzle that no one else reportedly could solve, Klausner was offered a position with H. Warshow & Sons, the elastic textile manufacturer. In 1950, he married Elizabeth Bloom — known as Betty — whose parents, exceptionally wealthy New Yorkers, thought the Jersey-born Klausner was utterly beneath their daughter. Betty, however, had ideas of her own. The day she met Klausner, she announced, “I just met the man I’m going to marry.”

When Bob and Betty moved to Santa Barbara in 1973, they bought a beachfront property near the Miramar hotel boasting some of the most spectacular ocean views on planet Earth. Their oldest daughter, Kim, had already grown up and moved out, and their son, Drew, was soon graduating, but their youngest daughter, Kathy, then 13, thought it insane that anyone would move from New York City. Over time, however, she recognized how happy her parents were, her father especially. “Both of them were able to do in Santa Barbara what they couldn’t do anyplace else,” she said. “Make an impact.”

“He didn’t talk about his accomplishments much,” Kathy said. “Mostly he was just dad.” Later, Kathy recalled how Chevron — one of the oil companies with which Klausner crossed swords — was trying to dig up dirt on her father to discredit him. “As a teenager, that was kind of cool,” she remembered. “That’s what you see in the movies.”

What CEC founder Relis and former Santa Barbara mayor Conklin saw in Klausner was a force of nature. At the time, the two were operating the Ecology Center. Conklin remembered “a whirlwind” dressed in coat and tie walking in the front door, “eyes bulging with a crazed look on his face.” Looking at the tall, thin, dark-haired man, talking a mile a minute in an unmistakable New York accent, Relis wondered, “Who the hell is this guy?” Turned out he was a man on a mission.

Mission number one was establishing a recycling program. Back then recycling consisted of newspaper collection drives by the Boy Scouts and the Mormon Church. But Klausner was all about business, recalled Relis. He negotiated a long-term contract with Garden State Recycling to buy recycled newsprint at prices which could not be lowered, no matter how violently the market price dropped. And he also got City Hall to lease an abandoned public-works structure at Garden and Ortega streets — now the Community Arts Workshop, where Summer Solstices floats are brought to life — to function as a recycling center for $1 a year. “We didn’t really know squat back then, but because of Bob, we were the only recycling operation in the whole state with a fixed contract,” said Conklin. “That saved us.”

Klausner didn’t stop there. He expanded the program countywide and then went after a contract with the brass at Vandenberg Air Force Base. This involved travels to Battle Creek, Michigan, New Orleans, and ultimately Washington, D.C., which Klausner paid for out of his own pocket. In D.C., Klausner and Conklin pitched to the assistant secretary of defense for environmental affairs. He listened and agreed. Relis was blown away. “There were no walls for Bob,” Relis said. Klausner always focused on the person, not their rank. Klausner told Conklin: “’Every man puts on his pants one leg at a time.’’

While Klausner is best known for his environmental agenda, he also worked quietly behind the scenes on homeless issues. Ken Williams, a former county social worker and longtime homeless-rights advocate, recalled being summoned to the Balboa Building to meet with Klausner. He wanted to help homeless people for whom a one-time infusion of cash would get them off the streets. There would be no grant applications or hoops to jump through. Klausner would provide the money; Williams would give it away, providing reports to Klausner later. Once, Williams recalled, Klausner was brimming over with tears. The program lasted about two years, and as many as 200 people were helped.

Bob and Betty Klausner quietly left Santa Barbara in 1993 with no farewell tour or orations. All three kids lived in the Bay Area by then, and the Klausners became doting grandparents. Bob got a $1 million Pentagon contract to suss out the viability of electric-gas hybrid cars, long before the Prius was invented. That effort would be stalled by an audit that — like the Chevron inquiry years before — yielded no dirt. To this day, Klausner’s daughter Kathy suspects the audit was politically motivated.

Over the past seven years, Klausner mostly took care of his wife, a victim of Alzheimer’s. In recent years, he, too, experienced dementia. Always the linear thinker, Klausner planned everything out meticulously, anticipating all eventualities in advance. His spirit stayed high. He recently told a friend, “I don’t do downers.”

Dave Davis vividly remembers taking Klausner’s phone call over the years. It was always the same low, smooth voice — very friendly, very deliberate, and absolutely focused: “‘Dave, I want to talk to you about something,’ he’d say.” Davis, who just stepped down from his perch at the CEC, described Klausner as an absolutely engaging human being. “Anytime you’d talk to Bob, you’d walk away feeling smarter,” Davis said. “I’m going to miss those phone calls.