The Appeal of Apeel

How a Company on Santa Barbara’s Eastside Is Fighting Food Waste, Protecting Produce, and Potentially Changing the World

Dreams to be, triumphs achieved, and challenges to come are exploding out of James Rogers’s mouth at a machine-gun pace. Printed on the staircase wall of his Eastside offices is the motto “Protecting plants as nature intended,” and that is the gospel Rogers is excitedly preaching to me. With a refreshingly boyish glee, he’s explaining how his company, Apeel, uses cutting-edge science to turn our country’s embarrassing amount of food waste into protective coatings that will make fruit, vegetables, and even flowers stay fresh way longer.

Recently, his team of scientists figured out how to better preserve cassava root, the staple starch crop for much of Africa, and he just won federal approval to sell Apeel’s product to American farmers. “I’m floating,” said Rogers, a Michigan- and Washington State–raised, Carnegie Mellon– and UCSB-trained materials scientist who founded Apeel in 2012 as part of UCSB’s new venture competition. Today, Apeel enjoys $2 million in grant support from, among others, the Bill & Melinda Gates and Rockefeller foundations, as well as $7 million in venture capital. “We’re cranking around the clock,” said Rogers. “Two years from now, I hope we’re making tons and tons of this material and it’s getting applied all over the planet.”

He’d just returned from a month-long trip to Nigeria, London, Chile, Madrid, and Abu Dhabi, and he was about to take off for Kenya and South Africa. “Our business is inherently international,” he said. “We have to go where the harvest is to do the application. We’re at the whim of the fruit.”

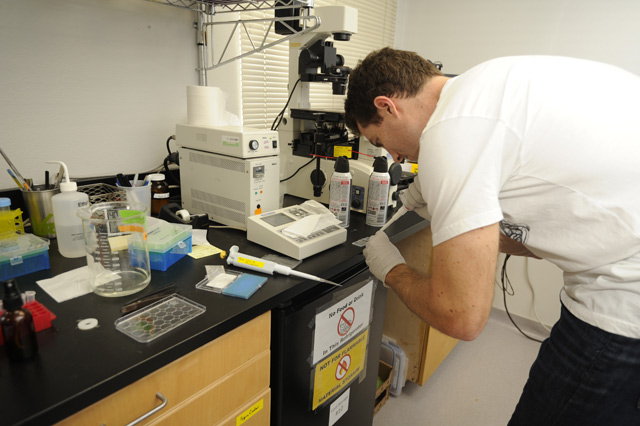

Apeel’s headquarters are located in a two-story office building on Reddick Street, around the corner from the taquerías of Milpas Street. Here nearly 40 scientists from various backgrounds — materials, like Rogers, but also biochem, mechanical engineering, and chemical engineering, among others — swarm around the open-floor workplace on the second floor, while downstairs, white-coated technians tinker in the various and evolving labs. Boxes full of scientific devices arrive by the hour, yoga mats hang from the balcony, and pale ale is on tap, yet still, no front desk exists.

This is what active innovation looks like, and if Rogers’s enthusiasm infers that he may be on the brink of changing the world, that’s because he is. Aside from 20th-century advances in refrigeration, there’s been very little work done on keeping food fresh once it’s harvested. “People have been trying to do this for a long time,” said Rogers. “Monks started waxing apples in the Middle Ages to preserve them through the winter. But there hasn’t been a lot of innovation in the last thousand years.”

Currently, about 80 percent of Apeel’s work is focused on the commercial produce market. Rogers’s first target is the blueberry because it costs a lot and rots quickly, among other factors. But he’s most fervent about the 15 percent of his company’s time that is dedicated to solving the problems of “post-harvest spoilage” in developing nations, where his product can help improve overall food security and bolster farming economies. The remaining 5 percent is being spent on continuing R&D. Among other long-term goals, Rogers believes that Apeel’s discoveries could one day replace conventional pesticides.

“We’re using food to protect other foods by applying materials science in a thoughtful way,” said Rogers, whose naturally derived coatings essentially stop water loss and oxidation, the main causes of rotting, but are completely flavorless, edible, and benign. “We’re not making something that nature has never seen before. We’re just moving it around.”

ike many a well-meaning UCSB PhD materials science student, Rogers was once working on flexible solar panel technology, which required frequent trips to Lawrence laboratory in Berkeley. One day while driving back to Santa Barbara through the agricultural sprawl of the Salinas Valley, Rogers wondered how in the world there could be so much global hunger when the country grows so much. “It was a really naïve perspective,” Rogers admitted.

He did some research and found that, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council, Americans throw away 40 percent of their food, which equates to $165 billion a year. “Even if that is off by half, the waste is just insane,” said Rogers. “Certainly,” he thought, “someone must be doing something about this.”

But no one was, so he started to figure out how to capture that trash — from grocery store throwaways and food scraps to farm clippings and used wine grapes — and redirect it into something beneficial, which is essentially what materials scientists do. “We bridge the gap between what’s available and what’s useful,” said Rogers, who began extracting potentially protective compounds from the waste while simultaneously producing greater quantities of those chemicals for testing purposes.

Since then, he’s been patenting both the organic and synthetic processes and products (which are chemically identical) and testing them all on various fruits, vegetables, and flowers. The Apeel offices have rooms filled with pineapples, avocados, strawberries, bananas, and roses where camera rigs take time-lapse photos showing of the effectiveness of the different coatings. “Every kind of produce needs different tweaking,” said Rogers, whose technology is making blueberries last four days longer and stretching avocados another 12 days, all without refrigeration.

“They are onto something potentially big in the produce world,” said Jay Ruskey of Good Land Organics, a farm on the western edge of Goleta, where he’s tested the product on finger limes and found that it does halt spoilage. “This is done without really hard chemicals/fungicides that are common today. They derive their ingredients naturally and, in a way, seem to mimic the produce’s natural defense but makes it much more robust,” said Ruskey. “It will be great to see where the company can go in the next 18 months.”

he science, while revolutionary, might be the easiest part of the Apeel equation. In the last three years, Rogers has endured crash courses in commercial farming and international food distribution, quickly determining that his most likely customers will be the grocery stores and processing plants that handle the produce. “They have the economic incentive to get this product to their suppliers,” said Rogers. That goes for American chains like Albertsons all the way down to the collectives in Kenya that move the cassava.

Though not technically philanthropic, Apeel’s African projects are more focused on goodwill than the bottom line, which is why the Rockefeller Foundation (which is fighting post-harvest spoilage in horticultural crops such as mangos and tomatoes) and the Gates Foundation (which is focused on staples such as cassava) have thrown support behind the company. “The foundation’s agriculture strategy is focused on empowering smallholder farmers with a variety of knowledge, tools, and technologies, like this one being developed by Apeel, to improve their livelihoods and lift themselves and their families out of poverty,” said Rinn Self of the Gates Foundation.

Meanwhile, Rogers will soon be enlisting his first American clients — three organic farms in the Santa Barbara area — to monitor how the product fares in the real world. He’ll even soon be building a sales room and, yes, a real front desk. “My objective is to be selling out of our stuff in the next six months,” said Rogers. Apeel’s current operation will be able to produce enough product to treat up to two metric tons of fruit per week. But Rogers is looking for a larger facility, even scoping greenhouses in Carpinteria for future R&D.

The only opposition he may face would be from individual growers who do well in the current system of waste, but he’s not too concerned. “Frankly, we shouldn’t be growing berries that we’re throwing away anyway, so I don’t feel too bad about that,” he said.

What he’s overjoyed about, though, is running a company that isn’t just about making money, and doing so surrounded by other scientists who feel the same. “We’re not making the next app to get you laid — we could actually move the needle here,” said Rogers, who’s proud to say that his 22 years of schooling have finally amounted to something. “We’ve had a lot of resources poured into us, and we’re applying our knowledge to benefit the greater good. What more could you want?”

See apeelsciences.com.