Not with words, but with a melody, Bill Connell told me what was on his mind when I picked up the phone: “Ta-didida-didida-didida-dah!” It was his rendition of the “call to post” that announces the arrival of horses on the racetrack.

“Bambi, I’ve got an itch,” Bill said. “The bugle’s calling. I’ve been selling hot dogs like crazy. I’ve got some money set aside. Pick a date. Let’s go.”

The winter meeting at Santa Anita was well into its second month, and we had yet to make our annual pilgrimage to the racetrack beneath the San Gabriel Mountains. I promised Bill I’d find a day that I could get away. That was my last conversation with him. Two nights later, he died unexpectedly but, by all reckoning, peacefully.

Fond memories will linger with his friends and his family in New Jersey — his mother, Betty Lou, and sisters, Maureen and Donna — where he raised hell as a young man. He will be missed by officials in his adopted state of California, with whom he sparred and whose support he won over as an advocate of military veterans’ rights; by the New York Yankees, who must have heard him hollering whenever they played games in L.A., Anaheim, or the Bay Area; and by the many South Coast residents and passers-by who visited him on the Carpinteria Bluffs, where he was endowed with a title: Hot Dog Man.

Connell’s All-American Surf Dog cart, located around the corner from the prime surfing spot at Rincon, opened for business on July 1, 1992. He sold his first hot dog for $1. When I met him, the price was up to $3, still a great deal. He smothered my all-beef dog with sauerkraut at no extra cost. Then came the best part of our encounter: an hour of banter while he continued filling buns for a stream of customers and handing out Red Vines to the kids.

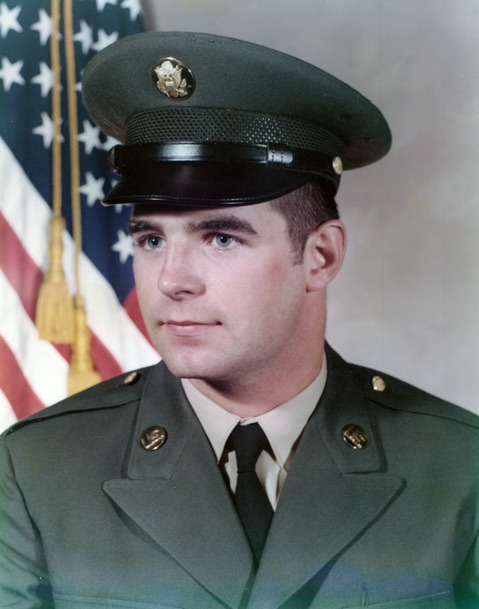

He came across as easygoing, but there was a glint in his eye that must have flared when he was in the boxing ring during the ’70s. He was the U.S. Army’s heavyweight champion in Europe, and he achieved a professional record of 14 wins (eight by knockout), four losses, and a draw. His sister Maureen said he worked as a bouncer at several New Jersey bars where Bruce Springsteen played, and some of Connell’s friends claim that he’s the character “Weak Knee Willie” in Springsteen’s song “Rosalita.” I prefer to think he is described in the next line of the ballad: “Big Bone Billy.”

The Hot Dog Man had a passion for baseball and horse racing. He told stories about his adventures in racing, like the time he had $300 riding on a horse at an upstate New York track that had been swamped by heavy rains. “He’s just killing it, yes, a 35-to-1 shot, bang, bang, bang, bang, all the way around,” Bill recalled. “Coming down the stretch, leading by 50 yards, he lugs in on the rail … hits his front quarters … flips up and over into a puddle, sucks in all the mud, and dies right there. I said, ‘Fellows, do you realize what just happened? We bet on a horse that drowned.’”

Several times a year thereafter, Bill and I went to the races at Santa Anita and Del Mar. He was an astute horseplayer. He did not believe in blind luck. He studied the Daily Racing Form, looking for clues that certain horses may be undervalued and ready to cut loose. They did not always come through, but we agreed that the next best thing to a good day at the races was a bad day at the races. The last time at Del Mar, one of Bill’s hidden gems finished at the top of a trifecta that he’d bet, and he came home joyfully with $3,000 in his pocket.

In another forum — rough-and-tumble state politics — Bill himself rode a long shot to the finish line by sheer will. He found a passage in the state Constitution that appeared to exempt military veterans who were vendors from collecting sales taxes. The state disputed his interpretation. After making numerous trips to Sacramento and piling up reams of documents — an aide to Assemblymember Das Williams displayed a bulging binder at Connell’s memorial — he finally was rewarded in 2010 by the signing of a law affirming his position.

On one of my darkest days, my spirits were lifted by the power of the Hot Dog Man’s oratory. With nothing to gain personally, he spoke out on my behalf at a rally protesting the firing of six reporters, including me, during the News-Press purge of 2006-07. Independent columnist Nick Welsh likened my situation to Bambi being murdered. From then on, Bill called me Bambi.

I visited his spot at the bluffs last week. It was decorated by flowers, flags, a surfboard, boxing gloves, a baseball, a cigarette — one of Bill’s vices — and a few other trinkets. Plans are afoot to install a permanent plaque on one of the boulders.

Surely he had his flaws as a human being, but during the time I knew him, Bill Connell was generous and kind. He wanted to make things better for people, not the least being his fellow veterans, many of whom fought in Vietnam. At the end of his memorial mass at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, a military honor ceremony was conducted. I heard the sound of another bugle, playing the long, mournful notes of “Taps.”

Rest in peace, my friend.