Fundamental to both judo and aikido is the art of the fall. During Kenji Ota’s 52 years as Goleta’s premier sensei in both martial arts, he taught more than 10,000 students how to fall gently, safely, and, above all, confidently. Or, as his wife, Miye Ota, described it, “to land as a cat.” Ken Ota, who died in November at age 92, operated out of a dojo he and his wife built — cinderblock by cinderblock — on Magnolia Avenue in the heart of Old Town Goleta. The structure was joined at the hip to Miye’s thriving beauty salon, where she made matrons of Goleta’s pioneering families look like the movie stars found in her waiting room’s glamor magazines.

When the Otas opened the studio in the early 1960s, large cornfields and tomato patches lay within easy spitting distance. Over time the area morphed from rustic-rural to aggressively unpretentious urban-utilitarian. Across from the dojo stands a self-serve car wash. Down the street, a Mexican evangelical church thumps out God-fearing rock music, a no-frills gym caters to the hard-core muscle crowd, and a hip-n-healthy restaurant seeks a toehold with the young millennial market.

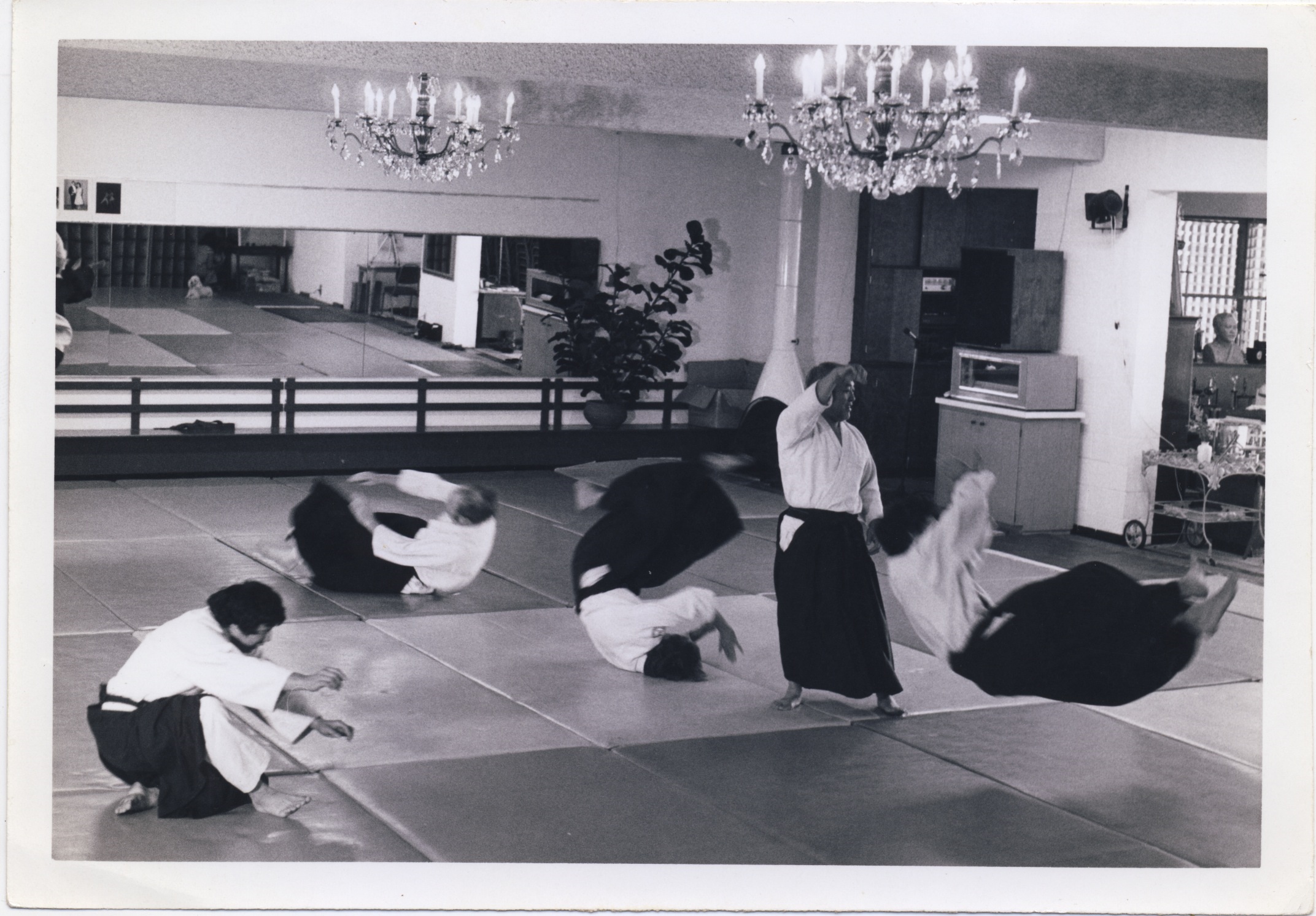

The Otas were not content merely to open a dojo for martial arts; they opened their Cultural School, too, for ballroom dance, cotillion, manners, and etiquette. Drooping from the ceiling directly above the training mats is the dojo’s famously incongruous chandelier. A sign on the wall ticks off five basic rules of conduct. “Respect your parents, instructor and the law,” reads the first. The last commands, “Always be a gentleman.”

The Magnolia Avenue school is where Kenji Ota — an award-winning ballroom dancer — started, but he expanded to Cal Poly, the YMCA, Montecito Country Club, and UCSB. At the latter, he was hired to teach judo in the early 1970s. The program was expected to fold, but it thrived under Ota’s direction. It grew to include a groundbreaking program for women, bringing some of the foremost women judo stars as teachers. He did the same for the university’s moribund ballroom dance program, also still going strong. Both are now taught by his 67-year-old son, Steven Ota. It wasn’t until two years ago that old age forced Ken Ota to give up any pretense at teaching.

None of this did Ota ever intentionally set out to do. Events conspired. One step begat another. Opportunity presented. And Ota responded as one would expect of someone masterful in the art of falling. “Sensei never went after things,” his wife explained. “He just fell into them.” In so doing, Kenji Ota — gruff, warm, commanding, and relentlessly generous — would become second father to countless students, his dojo a second home to many more. At a standing-room only memorial service held in the Cultural School in January, Steve Ota would say, “He was a guy from Lompoc. He taught a bit of dancing. He taught a little bit of judo. But he had this ability to look inside people and see the good and the potential.”

Kenji Ota was born in Lompoc, one of four kids and the son of Japanese immigrant farmers. That made Ota a nisei, or second-generation Japanese American. Lompoc held about 100 such families, who had their own agricultural co-op, church, general store, gas station, and judo dojo.

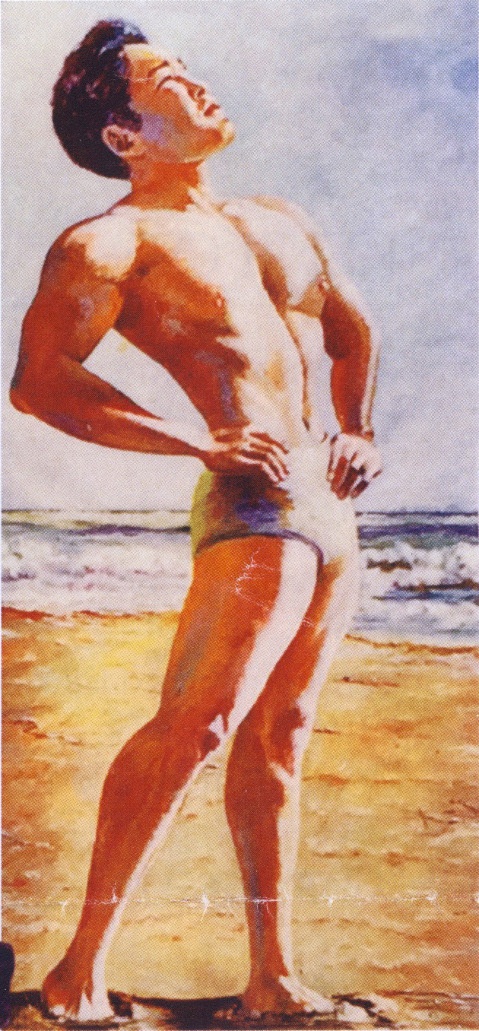

As a child, he’d suffered rheumatic fever, and, at one point a doctor told him the disease so weakened his heart he’d never be able to exercise. “He said, ‘The heck with the doctor,’ and went out and got barbells and became very muscular,” said Miye. By high school, Ota was avidly pursuing judo and body-building. The chief photograph at his memorial service was of a radiant young man in blue swim trunks — glorying at the beach in his strength and beauty.

As a teenager, Ota played football. He hung out with the team and hit as many barbecues as possible. On occasion, his wife said, Ota and his friends would raid watermelons from his own father’s farm. “His father would have given them the melons,“ she said, “but [Ken] thought it was more fun to steal them.” His father, Yasuke Ota, Miye recalled, took full advantage of the steelhead trout then coursing up the lower reaches of the Santa Ynez River; they swam in such abundance he could spear them out of the water with a pitchfork, a technique known as “Portuguese fly-fishing.”

In 1941, the Lompoc High School football team on which Ota played did something no other Lompoc team had ever done; they beat Santa Maria High School. “This was a big deal,” declared Lompoc journalist, sports writer, and historian John McReynolds, who wrote the book Vanished: Lompoc’s Japanese. “To avoid violence after the game, the Lompoc players had to get into cars and hurry home,” said McReynolds.

But as of December 7, no one cared who won that game. That was the day Japanese bombers wiped out Pearl Harbor, triggering America’s entry into World War II. At that point Ota became simply a Jap. Ota told McReynolds that he was working at a gas station at J and Ocean streets, pumping gas, when word of the attack hit. “A bunch of cars started honking their horns. They’d pull into the station, see him, and then hit the gas,” McReynolds said.

On February 23, 1942, a Japanese sub launched a few shells at Ellwood Beach. Only an oil company tool shed was destroyed, but the attack had broader ramifications. The process of rounding up issei (first-generation Japanese in America) and nisei families had already begun, throughout Lompoc and the entire Pacific Coast. After the Ellwood incident, it took off with a vengeance. By April, the Ota family — like most of Lompoc’s Japanese — were packed onto buses and hauled off to Santa Anita Race Track, where each family was assigned a horse stall. Soon after, they were taken to the Gila River internment camp in Arizona. Gila River had barbed-wire fences, a guard tower, and next to no privacy. It was also where Ota would meet his future wife, who grew up just outside Guadalupe near Oso Flaco.

The story goes that Ota was first drawn to Miye because of “her well-developed musculature.” In high school, Miye played many sports and edited the high school yearbook. She was a demon at field hockey, so fast she could steal the puck from opposing players at will. By any reckoning, Miye Tachihara was a firecracker. For Ota, she was the Fourth of July. But she was also five years his senior.

Miye initially rebuffed him. “I’d say, ‘Go away, you’re too young,’” she remembered. But Ota didn’t go. There were other issues, too. Ota had bad hair, Miye recalled, bad table manners, and spoke English with a thick Mexican accent he’d picked up from his friends. It’s a wonder, she acknowledged, they ever got together. “He was kind. That’s what won me over,” Miye explained. “Not everyone’s that way.”

Construction was still underway at Gila River when Ken and Miye were sent there, with long deep ditches everywhere. As they walked together one night, Miye recalled, she fell into one. Before she hit bottom, Ota “swooped me up,” she said. Even so, the age difference — he was 19, she was 24 — had to be addressed. In a dramatic role reversal, Miye said, “I had to get his father’s permission to marry.”

Nisei were allowed to leave the internment camps if they relocated away from the West Coast. In 1944, Ota moved to Philadelphia to work in a factory. He tried to enlist — the all-Japanese 442nd Regiment had established a reputation for bravery — but was turned down, physically unfit from the rheumatic fever that had left lasting damage to his heart. Miye followed Ota to Philadelphia not long after, and there they tied the knot. She opened a hairdressing business, and even with the war still raging, she built up a loyal clientele.

The Otas moved back to California at the invitation of Miye’s Santa Barbara beauty-school teacher. Matilda Green had stayed in touch during the internment, sending Miye cards at Gila River, writing words of encouragement and such pearls of advice as “be nice but not too nice.” Of the 100 Japanese families moved out of Lompoc, only two returned. What equipment they stored while in the camps was gone upon their return, their lands taken over. One farmer, Robert Hibbits, who’d opposed the Japanese internment hired Victor Inouye — a friend of Ota’s and an accomplished martial artist — immediately after the war; he got threats his barn would be burned down. Well after the war ended, one Lompoc gas station posted a “No Japs, No Germans Allowed” sign. Though Ota would return to Lompoc to visit and train with Inouye, he would not move back.

Steve Ota recalled his father never discussed the Gila River camp — “It’s not something he talked about” — but historian John McReynolds had a different experience. Most of the 80 issei and nisei he interviewed for his book avoided any such discussion. By contrast, he said, Ota was relatively forthcoming. “He remembered it wasn’t fair, and it pissed him off,” said McReynolds.

Upon moving to Goleta, Ota worked briefly on Dos Pueblos Ranch, then as a machinist for Western Welding. He attended beauty school briefly but was moved to start teaching judo in the early ’60s when his son got picked on in junior high school. He dug a big hole in the ground, filled it with sawdust, and covered it with a tarp — his first training area. There Ota taught Steve how to roll, fall, and to throw an opponent. Clearly, the lessons paid off. The bullies stopped bothering Steve, and soon other parents were asking Ota to teach their kids judo, too.

He “fell” into teen dance lessons almost the same way. He was shocked at the “pre-sexual” contact he observed when picking his son up from a junior high school dance. That would not be tolerated. In 1964 the Otas opened the dojo and cultural school, teaching boys and girls judo and how to dance. Some boys went reluctantly. When one refused to participate at all, Ota quickly changed his mind, throwing the adolescent “gently” to the ground. “That got everybody’s attention,” Miye said. Later, at UCSB, he would encounter the occasional arrogant ballroom student. Ota would observe with wry understatement how certain individuals were afflicted with “the disease of cranial-rectal inversion.” The problem quickly resolved itself.

Ota added aikido to his bag of tricks in 1963. It was first introduced to the United States in 1955, and Ota was intrigued by an article he saw in Black Belt magazine, which — as Steve remembered — “showed people throwing each other all over the place and smiling.”

As a martial arts instructor, Ota emphasized speed, timing, and rhythm. He went to elaborate lengths to help students overcome their natural fear of gravitational inevitability, setting up cushioned crash pads and ever-taller barriers. Then he’d hold a stick horizontally aloft even higher still. They learned to throw themselves further and faster, developing confidence in their ability to land without damage.

Sometimes he made students practice their routines blindfolded “to better feel the other person’s movement,” said Steve. Often he’d teach a sequence backward and forward. “He wanted to develop technique not just beat each other up,” Steve said. “Gentleness is stronger than strength.” But Ota could explode in a hurry when the need arose. About 10 years ago, four young men made the mistake of trying to mug Ota. They quickly found themselves airborne. “He taught people to be fast, fast, fast,” his son said. “On the street you have only a few seconds.”

On occasion, a street drunk or two would stumble into the dojo, most of whom Ota respectfully escorted out. Some were more insistent. A former student recalled how about 20 years ago one intruder came in and threatened to “Kung fu you and kick your butt.” Ota, in his seventies at the time, was in a back room. As the student attempted to respond, he recalled hearing “the shuffle of flip flops.” The intruder raised his fist at the student, and Ota inserted himself between the two, holding a Coke in one hand. Then Ota silently walked toward the man, backing him out of the building and to the curb. Not a word was spoken. Not a punch thrown.

The same student — who started taking lessons after winding up in the custody of county sheriff’s deputies — recounted how he called Ota one evening after his car broke down somewhere near Camarillo. Ota’s response? “Oh, I remember those strawberry fields.” Ota picked his student up, had the disabled car towed, and grabbed a quick meal at McDonalds.

At Ota’s memorial service, countless such stories were told. “Don’t try,” he would press his students. “Do.” One remembered lifting weights early in the morning with Ota, who was decidedly unimpressed by the student’s number of reps. “Fifteen is not a number,” Ota barked. “’Ow’ is a number.” Another student remembered Ota giving him a pencil with erasers on both ends, the point being, “It’s okay to make mistakes.”

The most repeated of all Ota’s many aphorisms, however, was, “If you can’t teach, you don’t really know it.” As a teacher, Ota could be demanding. On occasion, he’d softly whack students with his staff to correct their form. But he was forbearing of mistakes if effort was made. Ota taught by expectation. Based on the outpouring of stories told at his memorial service, it clearly worked. “He trusted us,” said one speaker. “He left us alone to become the people we needed to be and gave us the tools to do it.”

Not bad for someone who just fell into teaching.

Donations are being sought to repair the roof of the Otas’ Cultural School at gofundme.com/t8gubhbh, and checks can be sent to 255 Magnolia Avenue, Goleta, CA 93117.

You must be logged in to post a comment.