How memory is created in our minds, and where, is generally understood by neuroscientists, as are the brain processes that go into decision-making. But researchers continually want to know more. For sufferers of dementia or schizophrenia hoping for a cure, that’s a good thing. A study undertaken at UCSB’s Brain Imaging Center and published recently in Nature Communications takes a look at the anatomy of the brain in an effort to understand how its controls work.

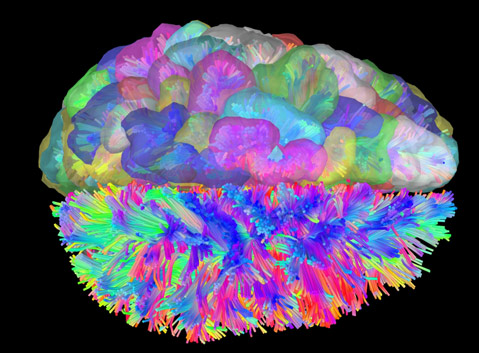

Cognitive function — or the process of perceiving and then understanding what we know — is one of the chief actions we ask our brain to do for us. By looking at MRI brain scans of volunteers from among the university community, UCSB professors Mike Miller and Scott Grafton and graduate student Matthew Cieslak investigated the workings of the mind, seeking to create an “electrical wiring diagram” that showed the relationship between its parts. The MRIs enabled them to see three-dimensional images of brain structures, including the white-matter fibre tracts, or bundles of axons, that connect brain regions.

What they and colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania saw was that the brain “wiring” confirmed what brain researchers already knew about brain function. The structural wiring that connected areas of the mind closely, also connected areas linked in thought or action. For instance, the different parts of the brain that might consider tonight’s dinner menu and then think about swinging by the grocery store have multiple and close physical links, or wiring, between them.

When they looked at the parts of the brain that would control the effortful change needed to get up from watching television and then go over to a computer to write a paper — a much more distinctly separate set of tasks — the “wiring” showed fewer and more distant interconnection between the regions of the brain that would control those two tasks, Dr. Miller explained.

Similarly, primal necessities like eating and food gathering that are in the middle brain are physically close to mid-brain areas involved in the “resting” state — the state when a person is not actively involved in a mental task. The transition from one to the other is likely eased by such close connections. The significance of the study findings is that the “wiring diagram” could be used independently to follow the transit of thought as a person changes tasks, or perhaps fails to successfully change to a different task.

For the treatment of losses of executive function — such as planning, paying attention, switching focus — being able to map the brain’s regions and their interconnections is a necessity, said Matthew Cieslak. Understanding these fundamentals of how the brain works, he indicated, were a step toward medical interventions to treat such conditions as autism, schizophrenia, and dementia.