Editors note: In the following story, we’ve respected the privacy of the spearfisherman by not publishing his last name. We ask that commenters do the same.

The hammerhead struck from the deep blue, jaws agape, blindsiding the spearfisherman across his left hip and forearm. For a split second, the blunt force of the impact made him think a jet ski or sailboat had hit him. When he turned to look, the narrow view through his dive mask filled with the hammerhead’s big black right eye. For another fraction of a second, he thought the eye was his own, as water often plays reflective tricks. But when the eyeball’s transparent membrane blinked, he knew exactly what he was facing. “Oh, no!” was his silent scream. Then came a violent swirl of bubbles, teeth, and blood.

This shark attack, which occurred on September 20 off the backside of Santa Cruz Island, is just one of several recent close encounters between humans and arguably the world’s most-feared predator. In the past six weeks alone, with the magnetic weather and exceptionally warm water, great white sharks have buzzed stand-up paddlers in Goleta Bay and flipped a kayak fisherman at Horseshoe Reef, off Summerland. Another kayaker, near Gaviota, repeatedly thwacked an aggressive hammerhead with an oar as the shark kept circling. This spearfisherman’s run-in, however, is the closest we’ve come to a fatality since October 23, 2012, when 39-year-old Francisco Javier Solorio Jr. was pronounced dead on the sand after getting bitten by a 15-foot great white while surfing at Lompoc’s notoriously shark-y Surf Beach.

Earlier this month, the spearfisherman, Matt (his last name has been withheld to respect his privacy), did agree, reluctantly at first, to tell his story to a few dozen, mostly younger spearfishermen gathered over slices and pitchers at a downtown pizza parlor. Matt’s initial hesitation dissolved when he realized his talk could save lives. He also wanted to throw a wrench of truth into the churning rumor mill. Within a few hours of the attack, wild stories had already begun to spread. In Carpinteria, a group of fishermen declared Matt had it coming after they heard that he had deliberately stalked and speared the hammerhead. Meanwhile, in Hawai‘i, his friends had gotten word that the shark wasn’t a hammerhead, but a great white, one of the ocean’s largest known species of man-eaters. Back home others speculated about the speed and comfort of his water rescue and helicopter medivac back to the mainland, when in fact he’d returned to Santa Barbara Harbor on the boat in which he had been fishing.

Free Fishing

Matt has been spearfishing and foraging coastally since the mid-1970s, growing up along the prolific waters of Monterey Bay. In 1981, he enrolled at UCSB, where he was a Division 1 swimmer, and started beach and boat diving along the coast and out at the islands. Now 51, he’s become a highly respected badass in spearfishing communities at home and abroad, diving about 50 days a year, mainly going after lobster, white sea bass, yellowtail, and tuna and other open-ocean species. His peers call him prudent and bright, a quiet leader and mentor.

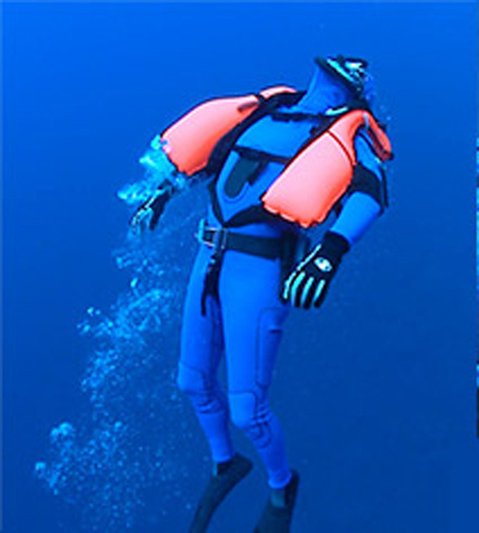

Like any self-respecting spearfisherman, Matt never dives with a tank of supplemental air (exhaled bubbles spook fish, anyway). He holds his breath — or free dives — propelling through open water and kelp forests with elongated swim fins and wielding the underwater equivalent of a crossbow and its razor-sharp spear tip. Breath-hold spearfishing is a primitive form of hunting which puts a terrestrial species into otherworldly oceanic territories fundamentally adverse to a relatively hairless, blubber-less air breather. There’s something to be said about a form of hunting that forces a good diver to adapt to a foreign world and discriminate by species and size before firing a single shot. The stealth, patience, and accuracy of it all take a lot of practice, but eventually some big fish will get the point.

Meeting the Hammerhead

About 10 minutes before the hammerhead changed Matt’s life forever, he’d dove on a school of yellowtail, abundant this year off Southern California, thanks to El You-Know-Who. Leveling off 20 feet beneath the surface, he drew on a nice 12-pounder about 15 feet away and released the stainless-steel arrow, known as the shaft. The pierced yellow died instantly — Matt had “stoned it” — and he pulled hand over hand on the shooting line, which attaches the shaft to the gunstock, to haul in his first fish of the day.

He then made a decision he would soon regret. The boat, which belonged to a friend who was also hunting nearby, was anchored about 150 yards away, up current. So instead of swimming the bloody yellow back to the ice chest, Matt strung it to his weight belt with a short length of cable called a stringer.

At that point, Matt was buzzing in the advanced stages of adrenaline and perceived immortality that comes with successful apex predation: He’s alone in the vast Pacific with a homemade speargun, and he’s just held his breath, immersed himself on the fringes of a bountiful kelp forest to stalk and dispatch his next meal with bull’s-eye precision. Fulfilling that genetic imperative put a smile on his face, and with the dead yellow dangling off his right hip, he reloaded. A few minutes later, another big school of yellows arrived. Same drill, and he’d speared a second fish. But this one was still alive, swimming frantic circles tight against the shooting line as Matt ascended to catch his breath. Then it happened.

Shark Repellants

Replaying the attack over and over again in the coming days on his couch at home — pushing through the post-traumatic stress — Matt was baffled why the hammerhead had not gone for the dead fish on his stringer. It charged in from the opposite direction and “tried to take me out,” he said.

During the first moments of the attack, Matt instinctually flipped through every trick in his mental book of shark repellants. Poke it in the eyes. Punch it in the gills. Ram it with the butt of his speargun. Matt had firsthand experience with these normally successful techniques from when he’d been attacked a few years ago on a trip to the tropics. In one instance, he was swarmed by a half-dozen Galapagos sharks — but never bitten.

Fortunately, the hammerhead got a bigger mouthful of Matt’s wetsuit than of his flesh — he would only need a handful of stitches — but his instantaneous demotion from King Neptune’s court to someplace lower on the food chain shook him to his core — as did the crimson cloud growing around him. Like most spearfishermen, he’s used to blood in the water. But this time, it was his.

Jagged teeth snapping just inches from Matt’s upper body and face, the hammerhead kept lunging and lunging. During the struggle, Matt’s dive mask came loose and filled with water. Meanwhile, the freshly speared yellowtail below — still connected to the gun by 23 feet of shooting line — was slowly looping Matt’s legs in a loose hogtie. Now on his back, partially submerged, with the shark on top of him, its back arched and its broad tail slapping against the surface of the water, Matt didn’t dare drop his guard to reach for the knife strapped to his leg.

“I felt like I was being sucked in by the energy of the shark, that the whole ocean was against me,” he remembered. “Why am I so far from the boat? Why am I diving alone? Why did I put this dead yellowtail on my stringer? Why won’t this shark stop?”

Gifts from El Niño

That last question is a good one, answered in part by all the warm water we’re experiencing, according to Dr. Chris Lowe, director of the Shark Lab at California State University, Long Beach. “Historical records show that smooth hammerheads [common from northern Baja to Cabo San Lucas] come up here during warm-water events like the one we’re having now. But there’s less food for them up here. They’re great scroungers; they steal fish from fishermen all the time. And in almost every case where a fisherman or diver says that a smooth hammerhead was being aggressive, there was dead fish or blood in the water. But if you were just out swimming or snorkeling, it would be very rare for them to approach you.”

The recent uptick in shark encounters should come as no surprise, Lowe added. “Shark populations are going up, we think,” in no small part to fisheries management. A boon for sharks was 1990’s Proposition 132, an initiated constitutional amendment banning near-shore gill nets, which had been inadvertently killing all sorts of sharks. Since 1994, great whites have been protected in California, and since last year, scalloped hammerheads have been protected under the Endangered Species Act. On top of that, during the past few decades, much more of Southern California’s offshore waters have been designated as marine protected areas off-limits to fishermen. And starting in 2012, our neighbors to the south shortened their historic 24-7, 365 shark-fishing season with an annual moratorium on commercial take between May 1 and July 31, when many species reproduce, according to Dr. Oscar Sosa-Nishizaki with the Center for Scientific Research and Higher Education, in Ensenada, Mexico.

The Worst Is Yet To Come

The hammerhead kept coming at Matt, now floating on his back, dive mask down around his neck. Just as he was running out of retaliatory options, Matt felt a bump against his right side. It was the speared yellowtail. As the hammerhead’s teeth snapped toward his face, Matt grabbed the wounded fish and shoved it in the shark’s gaping mouth. And just like that, the hammerhead turned away. A wave of relief flooded Matt’s pounding heart. “I’m not going to die.”

Then things got really dangerous.

As the hammerhead dove with the speared yellow in its jaws, the shooting line — still pierced through the fish — tightened it’s hogtie around Matt’s legs. Realizing what was about to happen, on the verge of panic, he took a deep breath just a split second before getting dragged under.

Oddly, any signs of panic faded away in the absurdity of the situation. The skies were blue and the ocean calm, the early-afternoon light refracted gold through warm, clear, familiar water. Ten feet down, his chest tightening with the first signs of oxygen deprivation, Matt decided: “There’s no way I’m going out like this.”

With both hands now relieved of shark-defense duty, Matt’s impulse was to fetch his dive knife to cut free the line tightening around both legs. But he quickly realized he had made another potentially deadly mistake: The shooting line was not his normal rigging of standard fishing-pole monofilament but rather the braided steel cable more common to his adventures in Mexico. His knife wasn’t gonna cut it. At this point, he’d been holding his breath for nearly 25 seconds, which, considering the situation, was a very long time.

Matt tried kicking toward the surface, but his legs were bound together. He switched to a dolphin kick, both legs in unison, perfected long ago during Division 1 butterfly workouts. As Matt ascended slightly, the shark’s head jerked sideways as the shooting line deep down its throat, still attached to the yellowtail, tightened. The shark fought against it, the back-and-forth jerking of its head creating brief moments of slack where Matt was able to unloop wraps of shooting line from around his legs. He tried for another, but he was now desperately out of breath. Then, in a last push to survive, Matt spun his entire body, unwrapping himself just as the darkness of unconsciousness started to creep in from the edges of his vision. At last, he burst onto the surface, sucking sweet air.

Calming down, Matt grabbed his first fish off the stringer and held it by the gills, ready to shove it down another shark throat should the opportunity present itself. Then he swam as fast as he could toward the boat, screaming for his friend and any other divers that happened to be nearby to get the hell out of the water. It later occurred to Matt that this would have been a good time to blow on a whistle strapped to his wrist. Except he didn’t have it with him. Perhaps it was time for free divers — especially buddy groups — to start wearing them.

Finding Safety Nets

On the lifesaving front, veteran spearfisherman and Ventura resident Terry Maas, 71, has finally, after about 12 years in the works, created what he considers to be the latest and best version of a computer-controlled buoyancy vest that automatically inflates when a free diver has been underwater deeper or longer than his or her preset parameters. Sharks, Maas points out, are the least of a free diver’s worries.

The sport’s biggest killer is drowning caused by blacking out when divers stay down too long. Often, the lights go out instantly. In the struggle with a freshly speared fish or in the scramble for lobsters, a diver’s body, which until then has been in the Zen state of the patient hunter, begins to rapidly burn up oxygen. “Just focusing on a goal so intently, our normal body functions are ignored,” Maas said.

Maas, who’s held the spearfishing world record for Pacific bluefin tuna, at 398 pounds, since 1982, lists drowning by line entanglement as the sport’s second-biggest killer. “A 30-pound fish can drag you under very easily,” he said. Boat strikes are the third culprit. Fatality by shark comes in a very distance fourth. Encounters are rare, and very seldom result in anything more than an accelerated heart rate. In the 56 years that Maas has been diving, he’s interacted with tiger sharks but never even seen a great white, though his best friend was killed by one in 1971 near Guadalupe Island, 150 miles off the west coast of the Baja peninsula. “That tragedy actually made me a better diver because I was always looking around for predators after that,” Maas said. “I would say that Matt has a couple of really good years ahead of him, looking over this shoulder.“

Home from the Sea

After a frantic sprint, Matt reached the safety of the boat. Small streams of blood pumped from his left hip through the jagged holes in his wetsuit. He yelled to his buddy to get out of the water. They motored to a nearby boat, frantically waving to a pair of free divers drifting nearby — a man and his 14-year-old son, who had just speared his first yellowtail.

With all divers out of the water and shock still numbing Matt’s mind to the psychic repercussions of the attack, he pointed the boat back toward the scene, hoping to retrieve his speargun. He had abandoned it during his fight with the shark, but he didn’t think it would be too hard to spot. He had rigged the butt of the gunstock with a long length of buoyant rope, to which he had fastened a small red buoy.

On the outside edge of the kelp forest, they spotted the buoy. Matt started hauling in the float line, effortlessly at first. Then he felt some weight on it. He looked down into the clear water. There was the hammerhead, alive, with the shooting line deep in its gullet, the swallowed yellowtail still strung by the cable and the attached spear shaft hanging out the other side of its mouth.

Matt got a good look at the now-listless hammerhead that had nearly killed him. It was about 10 feet long, bigger than your typical 8-footer but well short of the big guys — 14-footers — reported on occasion.

Carefully hoisting the hammerhead along the gunnel, Matt couldn’t help imagining how its jaws or even its entire head would look mounted on a wall at home. For a moment he stared into its big black eye, previously full of bloodthirsty aggression but now sedate and empty.

“Then a thought came to me,” Matt remembered. “He had me. Now I have him. Let’s call it even.” He asked his buddy to hand him the cable cutters. Matt snipped the shooting line and quickly retrieved both ends of the cable and the spear shaft. The hammerhead was free. It turned away from the boat and swam slowly into the deep blue.