Anyone who ever attended 4th grade at any California public schools during the past 50 years has probably been forced to learn how Father Junípero Serra — the 18th-century missionary who founded the first nine of the state’s 21 missions — hovers in the pantheon of founding fathers right up there with George Washington. For European colonials convinced they “discovered” California, Serra was the ultimate pathfinder, establishing new missions at a remarkably frenzied pace. Beyond that, however, little of the man radiates through the ages. For so pivotal a figure, Serra is strangely dull. Images are uniformly stolid and severe. Aside from what look to be — but aren’t — hair plugs sprouting comically from the crown of his head, he might as well be a big block of wood.

Nonetheless, Serra has been the subject of at least four new books in the past two years. Rousing new interest in Serra has been Pope Francis, who aggressively fast-tracked what would otherwise have been an uncertain path to sainthood for the polarizing California missionary, even waiving one of the key requirements normally required for canonization. The Argentina-born Francis urgently wants a missionary saint who brought the gospel to the New World. Despite vehement objections — leveled by tribal representatives and many historians — that Serra drew up the colonial blueprints that led to the physical and cultural extinction of many native peoples, it appears the pope will get his wish on September 23.

Of the new tomes on Serra, the one that exhumes the spirit of the man most vividly is Junípero Serra: California, Indians, and the Transformation of a Missionary by Rose Marie Beebe and Robert M. Senkewicz, the husband-and-wife team of historians who teach at Santa Clara University. To an exceptional degree, they manage to penetrate the historical mustiness that’s dogged Serra for so long. Beebe, a professor of Spanish, time-traveled through Serra’s vast trove of reports and letters, many of which are kept at Santa Barbara’s Old Mission Archives. Her translations detail various feuds, recollections, reports, and encounters that Serra had and wrote extensively about. The new translations pop with fresh energy and suck even the most reluctant reader in. Senkewicz, a professor of history and a former Jesuit priest, sets the context for these missives, explaining — with authority and restraint — what was going on with Serra at the time. Together, they manage to conjure a more complicated, intriguing human being than the Junípero Serra extolled by supporters or vilified by critics. Those searching for a clear and tidy resolution should look elsewhere, but for those comfortable with the clutter of human complexity, their book is a major contribution.

Santa Barbara Independent writer and wannabe historian Nick Welsh recently interviewed Senkewicz. The following is an edited version of their conversation.

There are so many books out on Serra. Why another one? What did you think you might find out that would be different? Rose Marie Beebe and I were doing some work on early California, and the missions always kept coming up. We’d consult the translations out there of Serra’s letters, and they were really, really stiff. So we began to wonder, “Serra can’t be that stiff.” We started wondering what a different translation of Serra’s letters would look like. That was the main thing. A lot of stuff on Serra, he’s presented in one extreme or the other: selfless, magnanimous saint or genocidal-maniac-type person. We thought let’s try to avoid the extremes and take him on his own terms and see where that leads us. That turned out to be something that hadn’t been done about Serra.

How did your translation differ than what had been done before? How does Serra shine through the ages in a different way? What happens is his emotions tend to come out more openly in the translation that Rose Marie did. He’s an administrator, so he writes a lot of boring bureaucratic stuff. Unfortunately, that tone in previous translations seeps into letters that are personal. We tried to separate those so when he’s writing another missionary or the governor, his emotions come out. This allows us to see him as a much more complicated, complex kind of figure.

There’s the instance where he’s talking to a fellow missionary who’s really depressed and wants to go home and Serra talks him out of it, but it’s really intense, and Serra’s eyes well up. That was in Baja California. Most of the books on Serra don’t give that a lot of space. We found that his emotions really come out there and also his excitement about being with unbaptized Indians, you know. That’s what he desperately wanted to do.

Why does this 55-year-old priest from Spain so desperately want to go to Mexico to be a missionary? Serra growing up on Majorca was a big deal. Majorca is a small little island, but it was at the intersection of a lot of trade routes in the Mediterranean, and he comes of age knowing that the wider world is out there. The other thing about Majorca — a bunch of people there had been missionaries among the Muslims in northern Africa; there was a missionary tradition. So when Serra begins to have this personal crisis in his mid-thirties — I resisted calling it a midlife crisis because that’s too Freudian — he’s not happy. He’s gotten to do everything he’s going to get to do. He’s got a chair at the university; he’s well known. But still, he’s wanting something different. He couldn’t move to a commune, you know, so he travels across the ocean to become a missionary.

When he was in Mexico, he was an agent of the Inquisition. You have these letters explaining how he interrogated a woman accused of being a witch because she practiced herbal medicine. Even in the context of his own times, he seems to have been really old school. He was forward-looking in some ways, but in others he always looked backward. He was an investigator of the Inquisition. That case involved a woman in a small village in the mountains of Mexico who’s accused of being a witch. Another lady had gone to her for healing. It didn’t work. So if the healing doesn’t work, she must be an agent of the devil. That is interpreted through the prism of the Inquisition, which is possession by the devil.

So what happened to this woman? She was sent to Mexico City and put in jail. She dies in jail. It’s not clear what the circumstances were — very vague, very murky in the documents. She is supposed to have suffered an accident. But she dies in jail.

But she was also accused of turning herself into a bat and sucking the necks of children! That’s a typical accusation that shows up in Inquisition records from northern Mexico. She also cavorted with Poway Indians. She probably had sex outside of marriage.

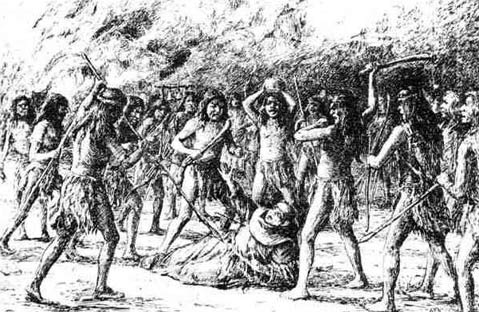

Other than his emotional expressivity, what surprised you? Serra’s time in California really gets divided into two: before the destruction of the mission in San Diego in 1775 and afterward. [Mission San Diego — California’s first — was attacked by about 600 Kumeyaay Indians and burned to the ground in response to the harsh punishment meted out there. One missionary was killed in the attack.] Before 1775, Serra goes to Mexico City; he gets an audience with the viceroy, the military commander, and he’s thinking things are going really well. He wants to do more missions; the world is his oyster. But after the destruction of Mission San Diego, the military people are saying, “No more missions. Look what happened at your first mission.” Serra gets kind of depressed, and he gets cranky, and until his death, he’s more sour than anything else. That surprised me. He’s still doing all the stuff he’s doing, but he gets more cantankerous and a lot less patient.

What’s the weirdest thing you found out about him? His notion that he was always right. He was an impatient guy, very self-assured. Probably overly self-assured.

You give the sense that he feuded with every governor, every military commander, and a lot of his missionaries, too. I don’t think he was an easy guy to get along with. He never met a military commander he liked. He got one fired; he didn’t like the replacement. He doesn’t like most of the soldiers he deals with. Some of his fellow missionaries find the guy wants do more and more and more, and the others are saying, “Hey, let’s slow down a little rather than running off and founding another mission.”

I was struck by how hostile relations were between Serra and the military commanders. You indicate it’s because he thought the soldiers were raping the Indian women and taking advantage of Indian labor. That’s exactly right. The relationship between missionaries and soldiers was always strained. Missionaries tended to regard themselves as the friends of the Indians, and they tended to think the Indians were their friends, too. The presence of soldiers at a mission was a visible sign that this self-image was incomplete. They had to be protected from the Indians. The fact is they needed soldiers, they knew they needed soldiers, but they didn’t like the fact. My own sense is they probably blamed the soldiers for too much. Much of the stuff about the soldiers mistreating Indian women was certainly true. But my own sense is that some of it may have been exaggerated in Serra’s writing.

You describe how he needed the soldiers on hand so the missionaries could flog the Indians, that if the soldiers weren’t present, the missionaries would be afraid to. There’s a great exchange with the governor Felipe de Neve and Serra. They clearly don’t get along, and Neve tells Serra just to flog them himself. What would be the offense to justify all this flogging? The flogging was generally for Indians who left the mission without permission, or if they had permission, they didn’t get back in time. Soldiers would be sent to bring them back, or friendly Indians would be sent. One of the things that missionaries never did was explain that as far as Catholic theology was concerned, baptism was a lifetime commitment; once you came into the mission, you had made a commitment to stay there the rest of your life. So you get guys saying, “I’ll come in to get my kid baptized; maybe the priest can cure him.” It doesn’t work, so they leave. All of a sudden, you can’t leave, because you made a lifetime commitment. But people left anyway. And they were captured. And if they were, the typical punishment was flogging with 25 lashes.

Twenty-five lashes! What was the whip like? It was the standard military punishment. Whips sometimes had little metal stuff stuck into it or sometimes hard cords with knots and things. The punishment was meant to hurt, and it did hurt.

Lots of people have said because Serra flogged himself he wasn’t doing anything to the Indians that he wouldn’t do to himself. They flogged themselves with little hand whips. It was meant to be kind of a penance. But you’re not flogging yourself for running away; you’re expressing a mystical identification with Christ, who was flogged before he was crucified. “I’m holding a little whip in my hand.” That’s a lot different than a soldier tying up an Indian and putting the Indian on a pole and giving him 25 lashes on the back.

How often did Serra flog himself? If not every night, then at least half the time. This was a regular thing for members of religious orders — especially male religious. They all did that thing back then.

Serra wanted to build a mission in Santa Barbara almost from the get-go. Why was he so gung-ho about Santa Barbara? This goes way back to 1769 and the Portolá expedition. They were blown away by the Chumash. The canoes, the tomols — they couldn’t believe how well constructed they were. Then the Chumash villages were very orderly, very well laid out; they tended to be a little more permanent than some of the other villages, and they reminded the Spanish of Spain. They thought these people are the most culturally advanced Indians. So if we can get these people Catholic, then the rest of the native populations would be easier.

Did it work out that way? When the whole mission system gets built out, there are more missions located among the Chumash than any other tribe in California. You’ve got San Buenaventura, Santa Barbara, La Purisima, and Santa Inés all very close to each other. But then in 1824, the Chumash rebelled. [More than 2,000 Chumash participated in the uprising against the missions and the Mexican authorities, who’d taken over from the Spanish three years before.] It turned out the Chumash were so sophisticated that they organized the most significant revolt against the missions in the whole mission period.

Based on the letters in your book, it was Governor Neve who prevented the founding of Mission Santa Barbara until two years after Serra’s death. There seemed to be a whole lot of intrigue going on. What was that about? Neve wanted to weaken the power of the mission system. He was going to make sure there was only one priest at the mission rather than two. If there’s one, that guy is going to spend all his time saying mass and hearing confessions. If there are two, one would take care of the spiritual, and the other would handle crops and material issues. After Serra founded Mission San Buenaventura, Neve saw that two priests had been installed there. Later, Neve goes to Santa Barbara and founded the Presidio. Serra thinks, “Okay, then I can found the mission.” Neve says you can’t. He’s doing that basically to spite Serra. This is Neve’s punishment to Serra for founding San Buenaventura under the old system of two priests, not just one.

Your letters make it seem really personal between these two. You’re saying it wasn’t? Neve really believed that missions were supposed to assimilate the natives and make them productive citizens of the empire and that they were only supposed to be around 10 to 20 years. The Indians would be taught Spanish, the missions would be turned into regular parishes, and the land would be divided up by soldiers. That never happened. The missionaries always said the Indians weren’t quite ready to leave. Neve thought if you let other missions get started, you’d never get these people out of there. Neve thought the primary institution for assimilation should be the towns not the missions. Bring in settlers. Let the Indians work for the settlers; the Indians would learn Spanish; they’d learn a trade, become productive; and the Empire would be the beneficiary. Neve founded two towns — San Jose and Los Angeles — and he wanted more.

As a former Jesuit priest, do you have any thoughts about making Serra a saint? I can see both sides of this issue. We started this book 10 years ago when this whole thing [canonization] was not even a possibility. The pope is from Latin America; the major person in the U.S. pushing this is Archbishop [José] Gómez of Los Angeles, who was born in Mexico. They’re very interested in having a missionary Hispanic saint who brought the gospel to a new area of the world. On the other side, I can understand how people who are opposed say, “You know, we always thought saints are supposed to be people who transcend their time.” Serra was in so many ways a man of his time. He doesn’t go beyond his time like Mother Teresa. Also, if you canonize Serra, then you’re canonizing the whole mission system, and that system was very much of a mixed bag.

As a historian, how do you see Serra’s legacy on the native populations? Serra was a colonial official. The missionaries’ salaries were paid by the government. They were part of the Spanish colonial system. Nowadays, the church missionaries wouldn’t act like this. They’d try to understand native cultures a lot more, but back then, the Spanish empire had military and religious aspects to it. The missionaries always thought of themselves as being the good guys in the colonial system. But they were, nevertheless, still in the colonial system.

Why would the Chumash go in there? There was food there. They may not like it, but there was food. The traditional way of life was impossible. There are diseases running around. There are no acorns left anymore [because of the colonial method of cattle grazing]. So what the mission had was food. The only other option was to go into the Central Valley, but there were already native people living there who wouldn’t be too happy with Chumash barging in. That was it for a lot of native peoples; it was a time of little choice.

How do you think Serra uniquely influenced the development of California Alta? What was unique to him was his pushiness, his determination, his commitment. He wasn’t going to wait. Some other missionary may have waited. He founds eight missions in the first eight years. Someone else might have said two or three would have been fine.

4•1•1

Junípero Serra: California, Indians, and the Transformation of a Missionary by Rose Marie Beebe and Robert M. Senkewicz (University of Oklahoma Press, 504 pages) is available now at bookstores and online.