Sports: Sam Cathcart Turns 90

Santa Barbara Football Coach Reminisces About His Life

Before covering a Santa Barbara High football game in 1969, I wrote up a preview that made the Dons sound like a junior version of the Green Bay Packers. Sam Cathcart was not too happy about that. The Dons’ crusty coach chewed me out over the telephone. “I’d be very happy to win by one point,” he declared.

That night, nothing went right for Santa Barbara. The visiting Simi Valley team capitalized on turnovers to score a big upset, 7-6. Approaching the coaches’ office after the game, I saw Cathcart through the window, smashing his clipboard against a desk. I did an about-face and wrote my story without any post-game quotes.

Thanks to my becoming wiser in a hurry, Coach Cathcart and I got along okay after that, and when he retired as the head coach after 19 seasons, he had compiled a record of 143-56-9 and led the Dons to 10 league championships. His great 1960 team, which won the CIF 4-A title, still gathers for periodic reunions.

Cathcart turned 90 on July 7. He is holding up rather well, considering he had a cancerous bladder and kidney removed not long ago. In a voice that has lost most of its gravel, he recently reminisced about his life, including an episode that many men of his vintage are reluctant to recall — the time he faced death and destruction in World War II.

“They called us the Diaper Division,” Cathcart said of the 75th Infantry Division that was training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, 70 years ago. “We were all so young.” Yet the army could not have drafted a fitter young man than Cathcart, an all-around athlete at Long Beach Poly High and Long Beach City College.

His family had migrated west from Canute, Oklahoma, when he was 3 years old. Scott Cathcart, one of Sam’s three sons, recalled watching the movie The Grapes of Wrath and remarking to his father, “This must really be a reminder of the way it was when Grandpa brought you guys to California.” Sam’s reply: “Hell, no … my Dad sold the farm, he had a plan, and he got a job right after we got here. You know, when the Okies came to California for the oil jobs, all the dumb Okies went to Bakersfield, and all the smart Okies went to Long Beach.”

It was near Omaha Beach on the coast of France where the men of the 75th landed in mid-November of 1944. They walked across the sands that were bloodstained on D-Day several months earlier. They were supposed to be an occupational force, but the anticipated surrender of the Germans was months off. Instead, they were thrown into the Battle of the Bulge, some of the bloodiest fighting of the war in the freezing Ardennes.

“Too many bright young kids died,” said Cathcart, who had attained the rank of sergeant and become a squad leader. “Even if you watch your step, sometimes there’s not much you can do about it. I figured I was one of the quickest ones, the wittiest ones. I was always alert. Some guys don’t do what they’re supposed to do. That’s why they get killed.”

Cathcart managed to send off letters to Susan Curry-Cathcart, his high school sweetheart whom he married during a furlough on May 8, 1944. “I’d write, ‘Hi, I’m still here’ — but I couldn’t say where,” he said. “‘Had beans for supper.’”

He had his closest brush with death on February 4, 1945, when his company advanced on the walled town of Wolfgantzen in the Colmar Pocket of France. A furious German barrage stalled the attack. “I never heard so much racket in my life — small arms, machine guns, bazookas,” he said. “It was boom-boom-boom. There was a tank behind me, and he wasn’t going to move until we did something. I decided to go after the machine gun that was doing most of the damage. I jumped into the machine-gun nest and started battling the four guys in there.” In the chaos that followed, the Germans were overcome, but Cathcart was wounded when metal fragments from a tank explosion tore into his right arm. He carried a more gravely wounded soldier to the safety of a farmhouse. Later, he learned that the young man had died. “That was the worst thing,” said Cathcart, who was awarded a Silver Star for his valor that day.

The American soldiers were deep into Germany on May 8, 1945 — V-E Day and Cathcart’s first wedding anniversary. “We drank champagne and stuff we’d saved for the occasion,” he said. During that summer, he ran the hurdles in the GI Olympics, a track-and-field meet hosted by General George Patton in Nuremberg. He came home early in 1946 with a broken ankle sustained in an army football practice. “I got out of the hospital in Van Nuys and hiked down Sepulveda to Long Beach,” he said.

He looked around the area for a college to attend on the GI Bill, and that fall he and several friends arrived at UCSB (then known as Santa Barbara State College and located on the Riviera). “We were PE majors, and we all graduated and became good teachers, principals, and coaches,” he said. Cathcart excelled at three sports — football, boxing, and track and field — and is in the Gaucho Athletic Hall of Fame. The football team, which practiced on a field off Foothill Road (site of the Tennis Club) and played games at La Playa Stadium, went 7-12-1 during the seasons 1946-47-48, but 6-0 against rivals Cal Poly and UC Davis.

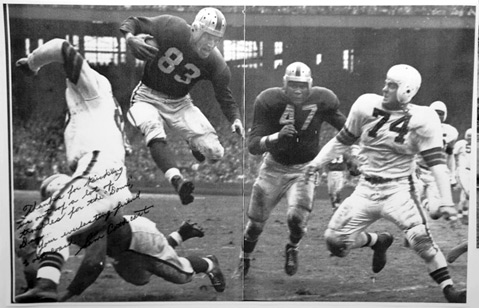

Cathcart’s prowess earned him a tryout with the San Francisco 49ers. He made the squad and played for three seasons, 1949, 1950, and 1952 (he served as a U.S. Army Reserve officer during the Korean War in 1951). “Pro ball was fun,” he said. “We didn’t have any classes to go to. I never missed a game or a practice.” He fought for yardage as an offensive halfback, intercepted seven passes on defense, and returned punts and kickoffs. “I hit the hole real good,” he said, “but I wasn’t quite fast enough to break it.”

Neither was he paid enough to make it with a growing family, so when an opportunity arose for him to take a teaching and coaching position at Santa Barbara High, he hung up his uniform. The Dons football team was the pride of Santa Barbara when the combat veteran became head coach in 1955. Even though he knew it was just a game, he took his job as seriously as if he were leading troops into enemy fire. When he sensed danger, he did not want a numbskull sports writer making his boys complacent.

Sam Cathcart, the lone surviving family member of his generation (Susan passed away in 2012, his younger brother, Royal, a year later), celebrated his birthday with his three sons, daughter, and grandchildren. According to the website oldestlivingprofootball.com, he is one of 64 former NFL players over the age of 90. He still lives in the Riviera home that was rebuilt after being destroyed in the Sycamore Fire of 1977. Many mementoes were turned into ashes, but there is a fresh new one — the replica of an engraved brick that will be on display in the new 49ers stadium in Santa Clara. The six-line inscription provided by his family, ending with a term of endearment, reads: “To Our Favorite / 49er Alum #83 / Sam Cathcart / 1949-1952 / We Love You / Bop.”