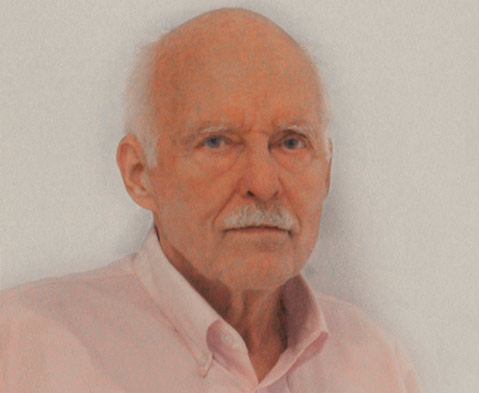

This year marks the 60th anniversary of modern solar cells capable of converting sunlight into useful amounts of electricity, and the man most responsible for converting a space-based technology to needs on Earth was Bill Yerkes, a longtime Santa Barbara resident.

Bill started his solar career back in the early ’70s with a company that manufactured solar cells solely for space. Then as now, solar cells powered most of our satellites, and life is unimaginable without the communication and navigation systems that depend on satellites. But Bill had a greater vision. Back when solar energy was only used in outer space, he wanted to bring it down to Earth.

After the company he headed was acquired by Hughes Aircraft with the intention of focusing solely on satellites, Bill left and started over in a garage. Bill and his colleagues began to design solar modules that could use mass-production techniques to bring the price down from their astronomical perch.

Among the innovations he pioneered, Bill identified a solution to the costly approach for creating the electrical contacts for the wafers of silicon used in solar cells. He hit upon the technique of screen-printing, just like silk-screening T-shirts. A special mix of silver flakes with glass powder formed the conductor and also adhered reliably. Bill chose tempered glass for the outer cover, as it was robust, manufactured everywhere, and would self-clean after a rain. The silicon cells were bonded to the glass just as auto windshields are made, because Bill had noticed that while car bodies rusted away in wrecking yards, the windshields still looked great, even after decades sitting outdoors. Thanks to Bill’s experimentation, the template for the modern solar module was born.

In his search for markets, Bill got a loan for a Volkswagen bus and began making runs to Houston because he’d heard the oil companies needed solar modules to run the lights and foghorns on offshore oil rigs. As Bill reminisced, “The oil-and-gas industry got us started. We had the solution for problems they faced, and they had the money to purchase the solar equipment that was needed. The market for solar kept pace with technology-driven cost reduction.”

The oil companies’ firsthand experience with photovoltaics convinced them of the technology’s potential. The skyrocketing petroleum prices of the 1970s led them to believe solar might one day replace coal for electricity. One company that Bill worked with — ARCO — offered him a proposition: If Bill would sell his upstart solar company, ARCO would finance the transformation of a cottage operation to a full-blown manufacturing factory. The offer enabled Bill to expand, and the resulting economy of scale offered a significant drop in price. By 1980, ARCO Solar became the world’s largest manufacturer of solar modules. More affordable solar modules opened up numerous markets, including running water pumps in drought-stricken Mali and lighting up houses in places that hitherto relied on candles or kerosene. The company continues operations today as SolarWorld.

A good friend of Bill’s, Charlie Gay, who was head of R&D at ARCO Solar and led the company after Bill left, tells a story about how Bill’s solar cells changed life in remote Papua New Guinea that goes something like this: Another of ARCO’s solar acquisitions, ECD, had a consultant named Dave Adler, who loved to travel, says Gay. One of Adler’s adventures had been a trip to Stone Age villages in Papua New Guinea, and the journey was anything but easy. Starting off with an air flight on Air Niugini from Brisbane to Port Moresby, New Guinea, Adler then spent two days on a jarring and gut-turning jeep ride over rutted dirt roads. This was followed by two days on horseback, explains Gay, then three days paddling a canoe upriver to a region where people still used volcanic sulfur and ash to tattoo chest markings of their headhunting exploits. When Adler at last approached the village, he could see children scrambling into the water to swim up in greeting. As the kids emerged from the water, pulling themselves up on the gunnels, every child was proudly wearing a blue ARCO Solar T-shirt.

Papua New Guinea had been Bill’s first large market for solar-powered telecom systems, and his briefcase proudly bore Air Niugini stickers for years. “Bill was magical,” Gay said. “His raw, positive enthusiasm was contagious.”

Bill Yerkes more than fulfilled his vow that he’d bring solar cell costs down to earth. By building the teams and technical foundations, he made today’s solar revolution possible. Imagine: silicon slices barely thicker than a human hair magically producing electricity but without burning petroleum or creating pollution, its only fuel coming from that nuclear fusion plant safely placed 93,000,000 miles away. Bill’s passion and inspiration live on in every watt of the more than 100 billion watts of solar powering the world today.

John Perlin is the author of Let It Shine: The 6,000-Year Story of Solar Energy.