California’s Island Winery, Reborn

Santa Barbara Family Realizes Historic Dream of Growing Wine Grapes on Catalina

After crashing through dry stalks of fennel, gingerly stepping over clumps of poison oak, and dodging branches of lemonade berry, Geoff Rusack crouched beneath a canopy of scrub oak, looked toward the sky, and pointed at a leafy green vine clinging to the top of a willow tree.

“That’s a zinfandel vine right there,” said the 57-year-old vintner with a boyish grin, happy to spend a spring morning trouncing through the foothills of Santa Cruz Island, the biggest of Southern California’s Channel Islands. “It’s crazy how this survives out here.”

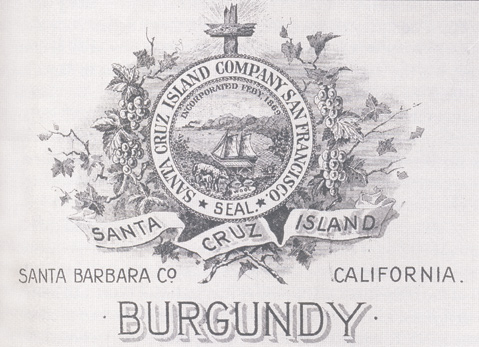

One of only four grapevines known to exist on the island, the hidden zin is a remnant of when this remote, 97-square-mile chunk of land off the Santa Barbara coast was home to a sprawling, thriving vineyard. First planted in 1884, the grapes were processed by renowned wineries throughout California — including under the Santa Cruz Island Wine label until it shut down in 1918 — and the estimated 200-acre vineyard even kept pumping through Prohibition. But then came the Great Depression, and away went America’s desire for fine wine. Following one last harvest in 1932, the vines were left to wither away, although you can still easily spot the vineyard’s footprint while flying over the east end of the island’s central valley.

Seventy-five years later, along came Rusack and his wife, Alison Wrigley Rusack, probably the only couple on the planet with the wealth, property, and know-how to bring winemaking back to California’s Channel Islands. The former aviation attorney’s requisite experience comes from 20 years of running Rusack Winery in the Santa Ynez Valley, but Alison is responsible for the rest: Hailing from Chicago’s Wrigley family, the former Disney marketing executive inherited a considerable chunk of the chewing-gum company’s fortune, including more than 10 percent of Santa Catalina Island, the third largest of the Channel Islands archipelago, located off of the Los Angeles coastline nearly 100 miles south of Santa Cruz Island. The couple hatched the idea for an island winery while riding horses on Catalina during their second date ever in 1983, but it took a quarter-century of planning for that dream to sprout.

Today, while zinfandel is the historic heart of their Catalina Island Vineyard, the couple — who reside mostly at their Hope Ranch estate — is also growing pinot noir and chardonnay, this past autumn harvesting more than 11 tons of grapes for their fifth vintage from the five-plus acres of grapes that now surround the family’s El Rancho Escondido, which was once the island’s main equestrian facility. After five years of learning how to tackle formidable and screwball challenges — yellow jackets, crickets, mildew, wind, salt, foxes, deer, quail, and even bison have all plagued the grapes, which currently must be hauled in multiple plane flights to Santa Ynez each harvest — the Rusacks are finally feeling confident that their vineyard will thrive. So they’ve signed up for even more struggle by updating and rebuilding the old rancho, complete with an on-site winery and tasting room that they hope will become a must-see day trip for tourists staying over the mountain down in Avalon.

Given the decades of planning, the astronomical costs, and the insane logistics required to start a serious agricultural operation in the middle of an island, what the Rusacks are doing at Catalina’s El Rancho Escondido represents a Hearst Castle for the 21st century — certainly not as grandiose in terms of cement poured, architects employed, and expensive art hung, but a monumental undertaking built to last for generations by one of America’s tycoon families, and one that reflects the modern world’s fascination with how wine can directly connect us to special parts of the earth.

“This is very much a legacy project for us, which Catalina has been all along for my family because we care about it so much,” Alison told me last summer, as we walked past construction debris on a hill that overlooks the vineyard and western coast of the island. “Each generation seems to add its mark. We seem to be the building generation,” she said, joking that her three sons will probably never go near a contractor again. “As the years go on,” she explained, as we looked out over the green rows of grapes, “Catalina is going to be more and more unique because the world is running out of space.”

A Tale of Two Islands

By the time explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo claimed the Channel Islands for Spain in 1542, the Chumash people had lived on Santa Cruz, which they call Limuw, for thousands of years and traded frequently with the Tongva people of Catalina, which they call Pimu, most notably for the soapstone chunks that Native Americans throughout California would turn into pipes, pots, and griddles. Both islands were considered and then rejected as sites for Spanish missions, and both became camping grounds for the Aleuts and Russians as they slaughtered sea otters to collect their valuable pelts.

Their trajectories diverge in the 1880s, which is when mainland developers from nearby Los Angeles started eyeing Catalina as a moneymaking tourist destination. A man from San Francisco named Justinian Caire had a different profit scheme in mind when he finally got the chance to see Santa Cruz in 1880, which was around the time that he had taken the controlling interest of the Santa Cruz Island Company, in which he first invested in 1869. Caire quickly began plotting an offshore agricultural kingdom based largely on sheep, cattle, and grapevines, which his family would eventually control for nearly 60 years.

In December 1884, while much of mainland California’s wine industry was getting hammered by the devastating effects of the pest phylloxera, Caire planted 4,000 vines from France, eventually experimenting with 20 different varietals, including the red grapes of cabernet sauvignon, pinot noir, petite sirah, grenache, malbec, and mourvèdre and whites of chardonnay, riesling, muscat, and trousseau. He built an expansive winery whose red-brick shell still stands today and grew the operation into one of California’s most respected sources of quality fruit and finished wine, which was sold in bulk to wineries from Napa to Los Angeles, as well as directly to the Raffour House Hotel across from Santa Barbara City Hall.

“[T]he general conditions for viticulture were good to excellent, the vine stock was of the finest, and the winemakers and cellar men were the best that could be found …” writes Justinian’s descendent Frederic Caire Chiles in his exhaustive 2011 book Justinian Caire and Santa Cruz Island: The Rise and Fall of a California Dynasty. “For example, the zinfandel was noted for being a full-bodied wine, fermented to dryness, with a higher alcohol content — qualities sought after in many of today’s top zinfandels.” With lawsuits, tragedies, and money troubles starting to affect the Caire family, the winery stopped producing in 1918, but the grapes kept growing into Prohibition, with fruit sold mostly to home winemakers until the Great Depression wiped out the project for good in 1932.

Down on Catalina, chewing-gum magnate William Wrigley Jr. cashed in on the Banning brothers’ failed tourist mecca dreams by purchasing a large chunk of the island in 1919, and he set about enlivening Avalon with a bigger hotel and casino, improving the infrastructure, enhancing landscaping, and increasing transportation from the mainland. He also established a quarry and tile-making company that produced popular pottery, built El Rancho Escondido into a premier Arabian-horse-raising ranch, and brought the Chicago Cubs baseball team, which he also owned, to practice on the island every spring. Upon Wrigley’s death at age 70 in 1932, his son, Philip, took over administration of the island and, in 1972, created the Catalina Island Conservancy, thereby donating 88 percent of the land to be preserved as open space into perpetuity.

At that time (though living primarily in Chicago with her father, William Wrigley III, and family), Alison Wrigley would visit the island most summers, and decided to attend Stanford for college. She never left California, eventually working for Disney. On a blind date in 1983, she met Geoff Rusack, the son of a Los Angeles Episcopalian bishop, who had returned to Southern California for law school at Pepperdine, having graduated first from Maine’s Bowdoin College. On their second date, while riding horses around Catalina, they discussed one day starting an island winery, and the dream that would one day reconnect the sister islands was set in motion.

Planting Problems, Harvesting Hell

Married with one kid and another on the way in 1992, the Rusacks started looking for a bigger house outside of Los Angeles and discovered Ballard Canyon Winery for sale. Though founded by dentist Gene Hallock in 1974 and warmly remembered by many for its annual grape-stomping parties, the 48-acre property was in “horrendous” shape, said Geoff, but they were intrigued. “It was before it was a chic thing to buy wineries,” said Alison, so the price was right. “We thought we’d run the winery on the side and keep our full-time jobs. We had no idea what we were getting into.”

With Alison working the books, Geoff got a crash course in grape growing, learning how to drive a tractor from regional pioneer Louis Lucas, and winemaking, with Richard Longoria leaving helpful tips on Post-it notes around the property. They replanted 17 acres on the vineyard’s “sweet spots,” said Geoff, and by 1995, the Rusack label — which features an old Catalina tile design — was on the market. But they kept returning to the idea of planting grapes around El Rancho Escondido, which was still owned privately by Alison’s family; Geoff’s drive was only empowered when he read Thomas Pinney’s book The Wine of Santa Cruz Island, published in 1994 by the Santa Cruz Island Foundation.

Meanwhile on Santa Cruz, The Nature Conservancy, which has owned the vast majority of the island since 1978, had its own problem: Many influential donors wanted the organization to bring the historic vineyard back to life, but it had neither the resources nor mission statement to do so. With rumors that the Rusacks were considering a vineyard on Catalina and wanted to look at Santa Cruz’s remnant vines — which had been identified years before by ranch manager Peter Schuyler and then found again by a subsequent manager David Dewey — Lotus Vermeer, who supervised the island for The Nature Conservancy at the time, was relieved. “This could be a very unique win-win situation where we can revise the history of winemaking and the old varietals on the Channel Islands and have somebody do it properly,” she told me during a trip to the island in 2012.

So Geoff and his sons Austin and Parker (their third son, Hunter, was away at college), climbed the island’s willow tree, took clippings, had them analyzed (one plant was the notoriously nasty mission grape variety), and propagated the zinfandel. In March 2007, after testing the climactic conditions and finding them much like the Russian River Valley in Sonoma County, they started planting the zin as well as pinot noir and chardonnay into a vineyard at El Rancho Escondido. Wine grape expert Larry Finkle, who works with Coastal Vineyard Care, said that the biggest initial challenge was the salty soils, which forced them to create a “complex system of drains and berms” that has “worked quite well but requires continued diligence.” Then came the plagues of pests both microscopic (mildew, fixed with farming techniques) and massive (bison, fixed with fencing) and the extra expenses required to fly products and personnel to and from Catalina’s mountaintop airport. “There has been an amazing amount of dialing in, but we have figured out how to deal with each individual thing,” said Geoff, adding, as he knocked on the wood table inside the rancho’s modest adobe, “We’ve had challenges across the board, but as we move forward, there aren’t that many more things that can hit us.”

With that confidence, the Rusacks doubled down on their dream in 2012 by pursuing a revamp of the ranch — “This is 70 years of deferred maintenance,” said Geoff — with the addition of a working winery and tasting room, which has required permits and review from Los Angeles County, the Coastal Commission, the Catalina Island Conservancy, the fire department, electric and water utilities, and more, not to mention the need to import a “megaton” rock crusher that required the costly rental of dozens of steel plates. Altogether, the project will wind up costing many millions, with hopes to be done within three to five more years, at which point tourists will be able to ride a bus to the property and sip some wine.

So How’s It Taste?

Though the historical ties and unique nature of an island vineyard seem enough of a selling point, the Rusacks’ Catalina Island project is intently focused on producing quality wine, a goal that was established under former winemaker John Falcone and one that continues under current winemaker Steve Gerbac. Said Geoff, “We want these grapes and this wine to be nothing short of world-class.”

They are off to a good start: The chardonnay boasts a touch of pleasant salinity that Geoff calls “coastal freshness”; the pinot, said Gerbac, is heavier bodied than what comes out of Santa Maria Valley and the Sta. Rita Hills despite being made in similar ways; and the zin delivers intriguing spices not usually found on the mainland. They aren’t cheap — $65 for the chard and zin, $75 for the pinot — and there is some consumer resistance despite the saga behind the bottle and the limited supplies: They hope to eventually get as many as 600 cases from the vineyard each year, but the 2011 harvest only resulted in the current release of 145 cases of chard, 118 cases of pinot, and 62 of zinfandel. But those prices are miniscule compared to what each bottle really cost: Geoff once told me it was probably about $500 a bottle, but later clarified that it “would be almost impossible” to calculate.

The Catalina vineyard is much more than just wine, though, and even California’s preeminent historian agrees. “The whole story is a case study in our efforts to recover California, and not in a purely antiquated way, but to recover a usable, useful past, in this case making wine,” said Kevin Starr, prolific author and professor at University of Southern California. “It is a luxury project, energized by very wealthy people, but that’s okay — it fits into the pattern of recovering California.”

Despite the challenges past, present, and future, the Rusacks remain enthused over the ordeal. “When I get over there and I can take a deep breath and look out and see those vines, I am pretty much blown away,” said Geoff. “I can’t believe we did this.”

4•1•1

Visit Rusack Vineyards in the Santa Ynez Valley at 1819 Ballard Canyon Road, call 688-1278, or see rusack.com.