Jesusita Fire Settlement Reached

Stihl Agrees to Confidential Payout for 60 Homeowners

Author’s Note: This is the start of a series of articles on learning to live with wildfire.

In a major victory for 60 of the homeowners whose houses were destroyed by the Jesusita Fire, Stihl Incorporated last week agreed to settle a civil lawsuit that claimed the company’s power tools ignited the May 2009 wildfire. The terms of the settlement were kept confidential.

The suit was brought on behalf of the homeowners by Los Angeles attorney Brian Heffernan, of the firm of Engstrom, Lipscomb & Lack. “This settlement provides a measure of relief for the homeowners who lost not only their homes and possessions, but, in many cases, irreplaceable items,” explained Heffernan, who has extensive experience in wildfire-related litigation and also represented a number of victims of the Tea Fire. The settlement was the result of mediation that was ordered by the court last spring, as attorneys were in the midst of deposing dozens of potential witnesses for a civil trial that was expected to begin this August.

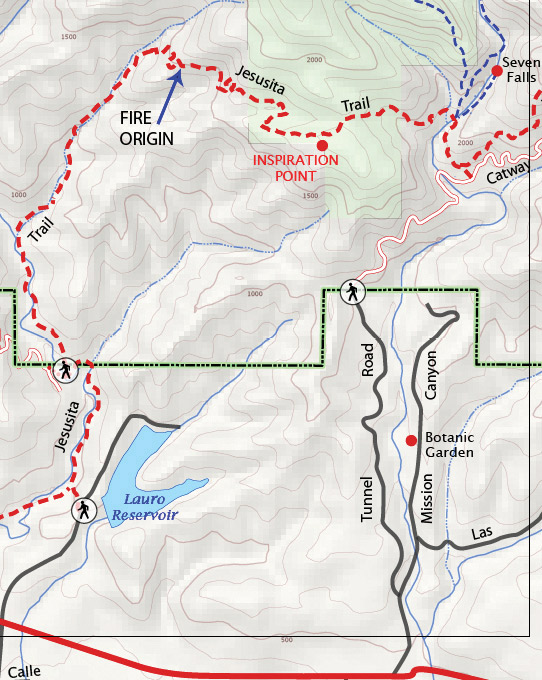

The settlement comes more than three years after the Jesusita Fire erupted around 1:39 p.m. on May 5, 2009, along a stretch of Jesusita Trail in upper San Roque Canyon. By the time it was contained 10 days later, the wildfire had burned 8,733 acres, cost more than $35 million dollars to fight, destroyed more than 80 homes and outbuildings, and injured 30 firefighters — three of whom required hospitalization for second and third degree burns. It’s believed to have been caused by Santa Barbara contractors Dana Larsen and Craig Ilenstine, who were seen clearing brush along the trail with power tools shortly before the fire erupted.

The suit was filed on July 14, 2011, about a year after Larsen and Ilenstine pleaded no contest to misdemeanor charges of using brush cutters without proper permits and fire suppression equipment. A previous attempt to prosecute the two for more serious charges was tossed out by a judge, so they were each sentenced to 250 hours of community service and three years probation. But given the destruction of so many homes and the serious injuries sustained by firefighters, many in the community felt that the pair got off too easy, and that frustration, said Heffernan, is what motivated numerous homeowners to file this case.

The lawsuit’s major allegation was that Stihl did not warn users like Ilenstine and Larsen that the metal blades of the Stihl FS 110 brush cutters could spark a wildfire in high-risk areas, a situation that would require a special label per the California Public Resources Code. The company countered that such sparks were insufficient to start a fire. Experts from Santa Barbara County Fire, CAL FIRE, and other agencies retained by Heffernan disagreed. Heffernan explained, “The defense in the case was premised on two fundamental untruths: that Larsen and Ilenstine did not work in the area where the fire originated on the day of the fire, and that, even if they did, the sparks for a metal blade like they were using were incapable of igniting a fire.”

The Investigation

The plaintiffs’ case was built on extensive investigations carried out by the Santa Barbara County Fire Department, which published their results as part of a 1,200-page report in August 2009. The department tested Stihl FS110R brush cutters at Lake Cachuma, and found that they ignited two small fires in less than 10 minutes. The flames seemed dependent upon wind, suggesting that the brush cutter could have created sparks that smoldered in the dry, cut grasses before bursting into flames when the breeze kicked up.

As for the suspects, both Larsen and Ilenstine were seen near the area where the fire started. George Burtness, a nearby resident who was out on a walk, heard the sound of the brush cutters a little before 11 a.m. but didn’t actually see who was doing the cutting.

However, a trail runner, David Thompson, who was heading towards Tunnel Trail a bit after 11 a.m., did observe them using the brush cutters near the top of a set of switchbacks and just below the Traverse. He later identified Larsen and Ilenstine as the two men he saw using the power tools.

Then, just after 1 p.m., as Robert Muraoka headed up Jesusita Trail on the first of his twice-a-week hikes on the trail, he spotted smoke and then the fire at 2:09 p.m. He later described the fire as “the size of the hood of a car” when he saw the flames and he immediately called 911 to report it. Muraoka also noted the presence of fresh-cut vegetation near the origin as well, indicating that work had been done along the trail very recently.

In interviews with both Thompson and Muraoka as well as images from a camera located at Cater Filtration Plant that looks out over the trailhead parking area, it became clear to the investigators that there were only four people who’d been up on the Traverse section of the Jesusita Trail between the time Burtness heard the sound of the power tools and Muraoka spotted the fire — the two trail workers, David Thompson, and Robert Muraoka. Additional questioning would later eliminate both Muraoka and Thompson as suspects.

Determining the Point of Origin

Looking to determine the exact spot where the fire started, CAL FIRE investigators Charlie DeHart, Eric Watkins, and David Cabral began an intense examination of the Traverse section of Jesusita Trail from May 8 to 11 while fire fighting efforts were still underway elsewhere. In his supplementary report for CAL FIRE, DeHart noted that they had found a number of fire indicators, including angle and depth of charred brush, sooting and staining, and other evidence that led them back to what they determined was the general point of origin just east of a spot on the Traverse known as “the nose.”

Their findings were corroborated the following day, Saturday, May 9, when Watkins and Cabral hiked the trail with Muraoka and had him point out the spot where he’d seen the initial flames. “The spot was consistent with the area we’d determined was the point of origin,” DeHart would later report. At this point, the fire investigators discovered a number of rock surfaces they determined to have been scarred by a metal blade like the ones Larsen and Ilenstine were using that day.

In the following weeks DeHart slowly began to eliminate other potential causes of the fire, such as lightning, smoking, campfires, vehicles, fireworks, power lines, arson, and the like. “Through my training and experience in fire investigations,” DeHart said, “I have concluded the fire was caused by the power equipment being used in one of three ways: The power equipment being used hit rocks along the trail, causing hot sparks from the cutting edge to ignite the light flashy fuels along the trail’s edge or the exhaust from the power equipment expelled hot exhaust particles into the light flashy fuels.”

Ilenstine and Larsen Come Forward

On Monday, May 11, while the investigators were wrapping up their initial investigation, Ilenstine’s attorney Sam Eaton sent a letter to Santa Barbara City Fire Chief Pat McElroy, indicating his client and another man, later identified as Larsen, had been conducting vegetation clearance on Jesusita Trail the morning the fire started. At that time, though, both denied any responsibility for starting it.

On May 14, search warrants were executed at the homes of both men, recovering the two Stihl brush cutters in the process, though one of the two metal blades used by them on May 5 was missing when the search warrant was executed. Extensive tests of both of the brush cutters later determined that they were in good working condition.

On September 2, 2009, Delgado submitted his report, concluding, “The decisions attributed to Ilenstine and Larsen during the investigation introduced the subject power equipment onto a brush-covered southern slope during weather conducive to vegetation fires….and appears to have caused the damage documented during the Jesusita Fire.”

Then in early December 2009, the Santa Barbara County District Attorney’s office filed misdemeanor criminal charges against Craig Ilenstine, 50, and Dana Larsen, 45, with one count of not obtaining a “hot work” permit. That is a violation of a California Fire Code, which requires a permit be obtained from the fire marshal for any “welding, cutting, open torches, and other hot work operations and equipment.” As reported above, the charge was dismissed by Judge Dandona in 2010.

Not too long after the dismissal, a determined effort by the Heffernan on behalf of the homeowners to recover damages through the civil courts began to take shape. Along with the homeowner lawsuit, CAL FIRE also filed a suit against Ilenstine and Larsen, hoping to recover in costs spent in fighting and investigating the Jesusita Fire. The CAL FIRE case against Larsen and Ilenstine was settled in December 2012 for a reported $2 million.

Focusing on Safety Issues, Not Settlements

“While the settlement was extremely important in helping the homeowners recover damages from the fire,” said Heffernan, “I think it is important that we focus on the safety issues that need to be dealt with if we are to keep this from happening again.”

“Use of power tools in high fire risk areas is a crucial fire safety issue,” Heffernan added. “I don’t think either of these guys felt like they were taking a big risk using power tools up there that day. This amplified a point we were making in the lawsuit, that users are not adequately informed of the fire risks associated with using a gas powered machine in an area like this. Even those with extensive experience with tools like Ilenstine and Larsen were completely underestimated those risks.”

“In the spring weeds are starting to flourish and get fairly high,” Larsen explained to fire investigators, telling them they were just out there to “cut on either side of the trail so that it was safe to pass through it and be able to see other folks and also to just keep it safe.”

“We thought we were doing good,” Illenstine added when investigators served the search warrant at his home, describing the vegetation along the trail as “waist high and at the point of swallowing up the trail.”

Both Ilenstine and Larsen were long time contractors, had hundreds of hours of experience using a variety of power tools and as long-time Santa Barbara residents were very familiar with the area’s fire history, yet despite this had almost no real understanding of fire, fire behavior or working in high-risk areas. In fact, Larsen lived in one of the high-risk fire zones himself and was forced to evacuate when the fire turned back and headed west across and down San Roque Canyon several days later. Despite this, he maintained in his deposition that what he did was safe. Fire officials disagreed.

What Will It Take?

Not too long after the Tea Fire — and just a half year before the Jesusita — members of the Santa Barbara City Firefighters Alliance called for a “public conversation” to discuss “how we protect our existing community from future wildfire disasters, and implement proven actions that firefighters know can protect our community.”

One of these is the need for much more emphasis on making people aware that using power tools in these fire prone areas, especially grassy and weed-covered areas, carries with it serious risks if conditions are not assessed properly. On May 5, 2009 Craig Ilenstine and Dana Larsen set out to cut some brush and to make Jesusita Trail a safer and more pleasant place to hike and ride. They’d done it uneventfully before and didn’t anticipate any problems that day either. Heffernan analogized this to texting while driving as an accident waiting to happen.

Larsen and Ilenstine described the temperature as cool, in the mid 60’s, with little wind, and a layer of fog in the earlier morning. When asked in his deposition if he and Ilenstine made a judgment as to whether the conditions were appropriate for using power tools on the Jesusita Trail, he replied, “Yes. We deemed them appropriate.” When asked later if he was fully aware of the potential for wildfires and the conditions that contribute to raising the risk of wildfire Larsen replied, “Fully aware.”

Yet all witnesses who traversed the trail that day, as well as weather reports, confirmed that it was a hot day with winds accelerating in the afternoon — quintessential fire weather, especially in a year that had lass than 6” of rain to date and was considered to be experiencing drought conditions by NOAA.

Turns out they were disastrously wrong on a series of levels: for the homeowners whose houses were lost; to the fire fighters who were injured during the fire; for the costs associated with fighting it; for the environmental impacts to the hillsides and watersheds; and on the lives of the two men who started it and their families.

Turns out no matter how long they lived here, how long they’d been working with power tools or how many fires they’d lived through in the past, neither Larsen nor Ilenstine adequately appreciated the dangers associated with using power tools in high fire risk areas.

The guess is they’re no different than most who live in Santa Barbara. The question is how we can better educate people who live, work, drive or play in fire-prone areas so they aren’t the next ones to create the spark that starts another fire like the Jesusita.

About This Fire Series

This is the first of a series of articles on living in a high fire risk community and learning to survive it. Shortly after the Tea and Jesusita Fires, which combined to destroy almost 250 homes and came close to costing several fire fighters their lives, it seemed time to begin taking a hard look at what it means to live with wildfire and what choices we can make to minimize impacts caused by disasters like the Jesusita Fire in the future.

Coming Next: An up close and personal look at the dangers firefighters face and what we can do to ensure they come home safely.