Body Donors

Cadavers Help with Scientific Research and Medical Teaching

I’ve been spending time lately with dead people. Recently, I was in a room with four of them lying on shiny steel tables, their bodies encased in what appeared to be zipped-up garment bags. This was the cadaver lab at Santa Barbara City College (SBCC), part of an uncommon educational experience available through the biological science department. It was there I encountered my first body, a female in her eighties whose remains both awed and unsettled me.

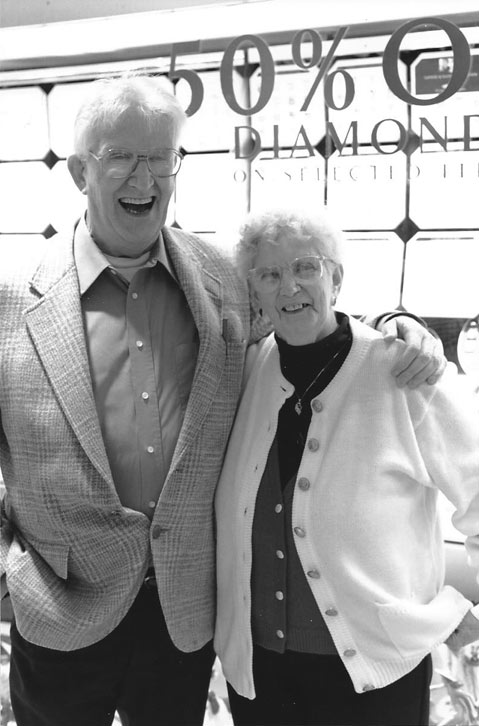

My visit with the dead started with a conversation. My friend Art Campbell had mentioned that he’d received an invitation from the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California to attend its Donor Appreciation Ceremony. He wasn’t sure he wanted to go.

Campbell’s father had suffered from a rare blood disease and made the decision to donate his body to science. His hope was that dissection would yield new findings for research. Campbell’s mother, then in the early stages of dementia, had followed suit. They’d filled out the necessary paperwork, put the donor cards in their wallets, and instructed their son to notify the school when they passed away.

His parents died within 10 months of each other, and Campbell dutifully, if reluctantly, fulfilled their request. A year later, the invitation arrived. “I was always torn by their decision,” he said softly, still struggling with the idea. “I understood that they had wanted to be of service, but I couldn’t stop worrying about the medical students: Would they be respectful? How would they treat these bodies who were my parents? I tried to separate their souls from their bodies, but the fears were still there.”

Different from an organ or tissue donor, the body donor’s cadaver is used for scientific research and medical teaching, primarily to first-year anatomy students. There are more than 100 universities nationwide with whole-body donation programs, and an estimated 20,000 cadavers are bequeathed yearly. Due to tightly regulated confidentiality rules, no information is supplied to the schools apart from age and cause of death.

Who are these donors and what propels them to go this route? Most are elderly, between the ages of 70 and 90, with altruistic motivations. They express the desire to be useful even after their death, to help prevent someone else’s suffering and potential early demise. Additionally, many professionals in the medical field donate their bodies as a sort of “pay it forward” credo for future doctors and nurses.

From a financial standpoint, the donation programs make sense, as well. The cost of a basic burial in the United States can be prohibitive, and this is a way to protect families from the burden of having to pay for the service. Howard Crawford, a Santa Barbaran who signed up for the Willed Body Program at UCLA more than 25 years ago, had this to say about it. “I’m not into funerals, and I don’t want my heirs spending a fortune just to bury me. My father was buried with all the pomp and circumstance of a full military funeral even though he didn’t want it, and my grandmother’s funeral cost her kids almost $20,000.”

Surprisingly, Crawford recently received word from the university that his body has been rejected because he’d subsequently donated a kidney to his son. Bodies may be turned down because of obesity or a history of communicable disease such as HIV/AIDS, but a missing organ is an unusual reason for rejection. Crawford said he will pursue other donation programs.

Rite of Passage

Historically, humans have had an uneasy relationship with death, especially in Western culture. Frankenstein and The Walking Dead are repositories of our deep discomfort, and we often shield our children from graveside proceedings. But death is a fact of life, and body donation plays an important role in training the next generation of physicians and scientists.

Dr. Barry Tanowitz, who teaches biomedical sciences at SBCC, served as my guide to this altered state. In his role as professor, Tanowitz instructs his young anatomy students in the ways of dissection — a true rite of passage. An affable man who looks more like a coach than a scientist, he is passionate about both his work and his students. The pupils, in turn, respect and admire him; one of them confided that she refers to him as the “Anatomy God” and finds herself constantly quoting him to others.

Tanowitz handpicks his team of students who do the initial dissecting to ready the bodies for the various classes. He is serious about the work, but not solemn, and he prepares his young scholars — many of whom have never encountered death before — with equal amounts of enthusiasm and respect. Trying to allay their anticipatory anxiety, Tanowitz tells them that “it’s so exciting to get a new body. … like the box of chocolates in Forest Gump, you never know what you’re going to get.”

When I mentioned that I have never seen a dead body, Tanowitz considered me for a long moment, and then he said, “Well, that could change.” I followed him to the lab, a cold room where the smell of formaldehyde assailed my nostrils. This is where students cluster around corpses and big plastic containers holding various body parts (Evan Sands, a first-year medical student at Michigan State, said it was a tough moment when he saw the bucket labeled “penises”). The professor and his two young assistants were like forensic sleuths as they held up lungs to show me the difference between healthy and not. “This is perhaps the most surreal experience of my life,” I said, and yet it all felt perfectly normal and scientific. Embalmed more than a year ago, the corpse looked like something out of a museum except for the hands and feet, which were eerily human. As Tanowitz said, “Nobody gets out of this alive,” though we pretend we will.

The students uniformly endorse these close encounters. Even with plastic body models and virtual technology (you can actually watch dissections on YouTube or download an app), there is nothing like the “real thing,” according to Sands. “There is no substitute for working with cadavers. Dissection gives young doctors an appreciation for the wonders of the human body. You need to feel the weight of everything and explore the intricacies.” Sands, who grew up in Santa Barbara, referred to the process as a “privilege” and recalled that his first dissection really solidified his desire to be a doctor.

Tanowitz added: “Models are good, but what the students learn here is the amazing variation between bodies. We are so fortunate to have an administration that supports us and understands the value of hands-on, interactive ways of learning.”

Luke Barrett, a 28-year-old SBCC student, said Tanowitz is the most amazing teacher he’s ever had. “He’s brilliant — one of those professors who will bend over backward for us. He’s the best resource I could possibly ask for.” Barrett, who plans to study physical therapy, has attained the coveted position of Student Coordinator for the dissection program. A mentor for the new students, he has already spent hundreds of hours in the lab and feels very honored to have been given the opportunity.

For Sands, “This is the most selfless thing one can do … to give up your body for the education of someone you’ll never know.”

Shona Beatty, a 22-year-old anatomy student, finds fingernails and toes, and hair on arms and legs unnerving. Still, she is fascinated with rolling up the skin and subcutaneous fat. She’s discovered that arteries, veins, and nerves vary from body to body, differing substantially from textbook diagrams, and that the chemical smell can be intense. Dr. Doug Jackson, who graduated from med school nearly 40 years ago and has a successful practice in town, can still remember the smell of the embalming fluid — and that nobody would sit near him in the cafeteria after his lab period.

Adding a little levity to the science, the American Association of Anatomists, the professional center for the anatomical sciences community, sells T-shirts with slogans like “Anatomists Get Under Your Skin” and “Bone to be Wild.” But in Tanowitz’s lab, macabre humor is rare, usually a nervous reaction that manifests mainly in nicknaming the cadavers. By and large, however, anatomy professors are very adamant about respecting the body, and the overall tone is one of reverence and appreciation.

At the behest of his wife, Art Campbell trepidatiously agreed to attend USC’s donor ceremony, if only to provide “closure” for himself and his family. The 75 students, through readings and music, expressed deep regard for those whose “ultimate gift contributed so significantly to their medical education.” Campbell was touched by the sincerity and desire of the students to personally thank the families of the donors. “This experience,” he said, “gave me a sense of hope for this future generation of professionals.”

Bodies as Business

The majority of programs are connected to schools, but there are also for-profit brokers who sell cadavers to various research and medical institutions. Although it is illegal to sell human bodies and body parts, these companies charge handling fees that can tally up to $20,000 per body. In his book The Red Market, investigative journalist Scott Carney postulates that the global body business has become a multibillion-dollar underground industry, fed by the growth of new medical research and technology.

The lucrative trade of cadaver acquisition is ripe with tales of body snatching, murders, and illicit incidents. As recently as 2004, UCLA’s Willed Body Program’s director, Henry Reid, was arrested for “illegal activities involving the commercialization of human remains.” He and an associate were selling body parts to private medical and pharmaceutical companies, netting over $1 million. After the scandal, UCLA shut down the program for almost two years and has subsequently installed oversight committees with reforms that include implanting barcodes and radio-frequency identifiers in cadavers.