Name of hike: Loop backpack from Cachuma Saddle to Upper Oso, mostly in the San Rafael Wilderness (in Los Padres National Forest)

Mileage: 38.6 miles over San Rafael Mountain and across the Mission Pine Ridge, then down to Coche Camp, Flores Flat, and Santa Cruz Camp, and over Little Pine Mountain to Upper Oso Camp (second car here)

Suggested time: 6 days/5 nights without a layover day; bring light backpack with food, safety gear, maps, and a solid hiking companion

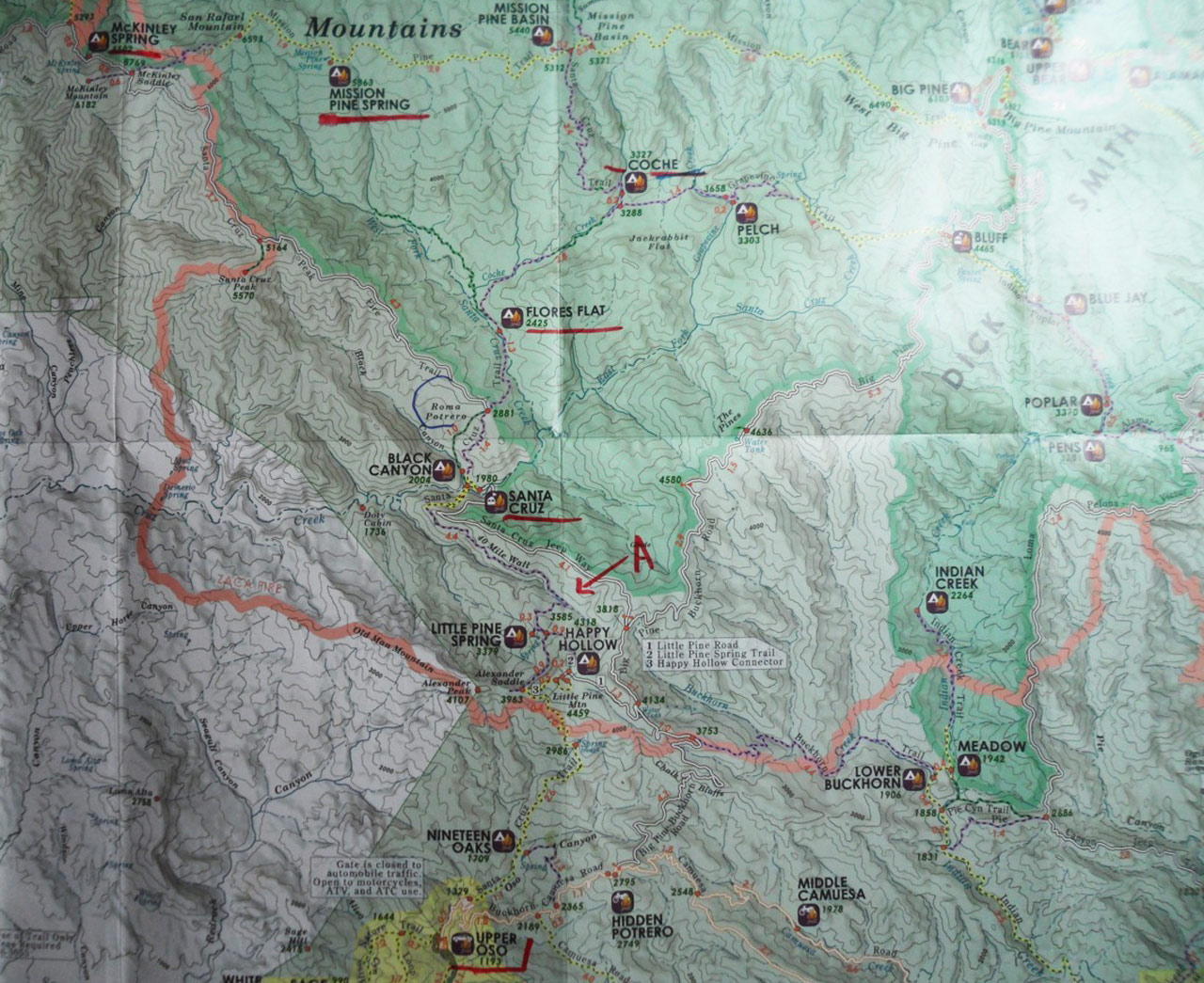

Maps: Bryan Conant, San Rafael Wilderness Map Guide (2009 edition, not 2003 edition); Ray Ford, San Rafael Wilderness (1986 edition, “the red map”); USGS topo maps including “San Rafael,” “Big Pine,” and “San Marcos Pass”

Thank you:Santa Barbara County Search and Rescue; and Chris Caretto

Somewhere the Buddha has stated that our big mistakes should be amazing opportunities to learn, otherwise we waste all the suffering that ensued from the error.

The absolutely exciting and uplifting 39-mile backpack my teaching colleague, Chris Caretto, and I recently completed illustrates the Buddha’s point, since I made a major hiking blunder and paid a pretty uncomfortable penalty, which seems fair enough. Since my disastrous wrong turn on the Santa Cruz Trail occurred during the seventh day of our trip, it will come up at the end of this article when we look at that last day’s 11-mile backpack over Little Pine Mountain.

Chris and I figured an almost-40-mile backpack up to elevations as high as 6,600 feet would be a little bit taxing, despite training for it, and we carefully planned on six days of backpacking, with one layover day just to explore the rocks and to rest up at the most beautiful sub-alpine Mission Pine Spring Camp (5,800 feet).

After dropping one vehicle at well-known Upper Oso Camp, near Red Rock, we drove on out Highway 154 to the Armour Ranch Rd. turnoff at the concrete Santa Ynez River bridge, turned right again on Happy Canyon Rd., and drove to Cachuma Saddle (3,100 feet) where I parked at about 5:30 a.m. on June 26.

We double-checked our equipment. My Osprey 6500 backpack weighed 39.5 pounds, far too heavy, yet I did have seven foil meals for suppers, eight oatmeal breakfast packets, and 12 rolls plus a heavy tube of peanut butter for lunches. (Look at the box, “My Stuff,” at the end of this column and note the section showing what I chose not to tote for 39 miles.)

The first day, starting off in the early dawn at 5:45, was relatively simple if demanding. We hiked 8.6 miles up the nicely groomed McKinley Mountain Road, ultimately gaining about 2,400 feet ascending the dirt road.

At 3.9 miles there is a spring (marked on Conant’s 2009 map, below) where we found a table, a water tank, and water. Since we could not have been sure in advance of this water source, Chris had carried four liters of water and I had lugged three liters.

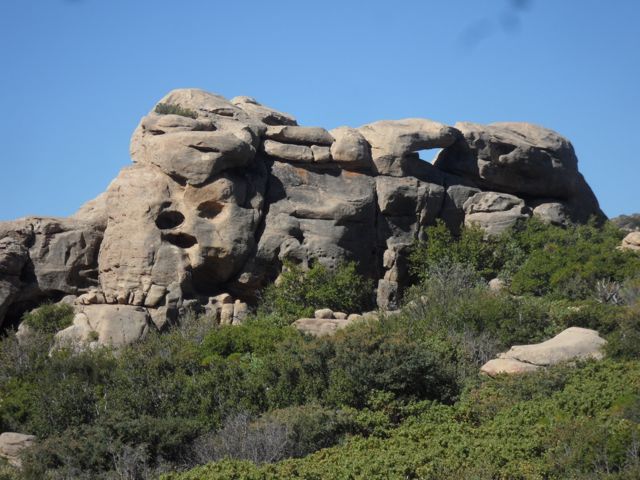

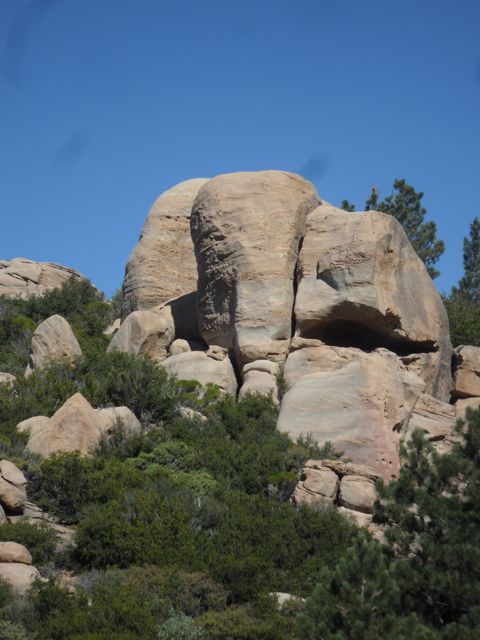

We trudged on in the early morning cool and, at about six miles, struck the gorgeous, rocky scramble area called Hell’s Half Acre on various maps.

This rocky maze is quite a wonderland, rather like Santa Barbara’s Rocky Ridge peak, but much larger in extent.

I camped overnight here with my young son in 1990s. There are spectacular formations, wind caves, and really interesting nooks and crannies in these weird stones. We pushed on, however, after vowing to explore the area another day.

The elevation gain is intense over the last 2.6 miles, and I was fatigued by the time we dropped into McKinley Spring Camp with its reliable water supply, two tables, and slanting camp space below the road itself. Here, at 5,500 feet, McKinley feels almost alpine, and we’re surrounded by a mixture of large black oaks, bays, and hard chaparral. The spring is piped out of the rock into a tank, and flows steadily: delicious!

Day two was shorter but not easier as we packed up to McKinley Saddle (see map), then over 6,590-foot San Rafael Mountain, the peak giving its name to the entire federal San Rafael Wilderness, which we officially entered above McKinley Camp. It’s the second highest point in the San Raf Wilderness (after 6,760-foot Big Pine Mountain).

The area is remote and wild, with mountain lion, black bear, deer, condor, rattlesnake, and a surfeit of lizards and crawling insects, but very few humans. The last segment of the five-mile backpack is a steep descent down a coniferous draw into the gorgeous glade of fabled Mission Pine Spring camp.

This fragrant glade situated at nearly 6,000 feet has been blessed, as Bob Burtness has written, with an excellent spring and splendid conifers, including incense cedars, ponderosa pine, manzanita, black oak, and a heavenly scent. Dennis Gagnon writes how this sacred space “is remote, secluded, and truly beautiful.” Soul rest supreme starts silently near here. The neighboring rock formations are oddly deformed and intensely interesting, made for clambering about.

We encountered a gracious solo backpacker at Mission Pine Springs, a Terry J., and he had packed in bearing just 26 pounds. He looked 50, hiked like he was a fit 30, and was in his early 60s, he told us.

The Trappist monk Thomas Merton writes, “the geographical pilgrimage is the symbolic acting out of an inner journey,” and I am very thoughtful about the fact that my 14-year-old son and I made a backpack here in 1997 beneath the full moon; I can feel his presence here in the sounds of the majestic pines. Merton also noted how “our real journey in life is interior: it is a matter of growth, deepening, and of an ever greater surrender to the creative action of love” in our hearts. Going deep into wild nature on the outside, with certain risks, I also hoped to journey as deep within.

Chris and I knew Mission Pine Springs would be the best site of the week-long adventure, and planned to spend two nights here, which we did, exploring the rocks, chatting with Terry until he left (in tennis shoes for the 13 miles back to his vehicles at Cachuma Saddle), observing the birds, and admiring the magic spring.

We reluctantly departed MP Springs early on the third day, aiming for Coche Camp, 7.5 miles away through Mission Pine Basin and descending through an almost completely scorched zone from the 2007 Zaca Fire. It was green and lovely for about a mile past Mission Pines Spring, then we dropped into the lower and heavily burned zone.

Once-beautiful MP Basin Camp (see map), built in 1924, was a black hulk of a ruined site, but the iron implements are fascinating. We spent a luckless hour here trying to locate a putative water source, but it is just a dry camp. While descending

2,000 feet in 3.4 miles from the Basin to Coche Camp, on innumerable switchbacks amid extremely poor trail conditions, we often simply had to guess, and bushwhack along searching for trail signs on the steep descent. From time to time there would be very small, pink plastic tags tied onto hard chaparral bushes; these were very necessary and welcome, indeed.

Coche Camp is a rough place, but it was the first water we encountered since leaving Mission Pine Springs, 7.5 miles behind us. Coche Creek itself was lovely, and we filled our canteens again and again, and made an overnight camp here because the constant downhill is as exhausting as the incessant uphill. Well-worn knees dislike plunging downhill on non-existent talus trails.

We were already contemplating the tough final day, with its 11-mile backpack, so we planned two easy days from Coche: 2.8 miles along the creek to glorious Flores Flat Camp and then 2.7 more miles from Flores to Santa Cruz Camp, on the creek of the same name, for final night six. Terry J. had been an amiable host at Mission Pine Springs, sharing the single table yet maintaining his reflective position. However, during the entire first six days of nature-glory, we never saw another human body or soul.

Santa Cruz Camp (which had been my April goal during the aborted Search for Sacred Springs backpack on Little Pine Mountain) is a large USFS campsite with five tables and at least 6 spots with fire rings and iron grates. There is a classic old Forest Service cabin here, built in 1931, and I understand that the firefighters during the 2007 Zaca inferno managed to save this historic cabin and some of the huge old oaks and sycamores.

There is an alternate way out, one I would come to reconsider on the fateful final seventh day. The Santa Cruz Jeepway dirt road, shown in white on Conant’s 2009 map just above the massif labeled “the 40 Mile Wall,” weaves its way northeast of (behind) this “wall” for over 14 miles to Upper Oso.

During our last morning at Santa Cruz, Chris and I realized what a marvelous, quiet, reflective journey this had been for each of us. I had been doing interior work on “kenosis,” an ancient Greek idea that means “emptying the mind.” Try it sometime; it’s very difficult for Westerners. As this external 39-mile odyssey wound down to the last long backpack on auspicious day seven, on the final night, Chris and I briefly discussed how I would leave about 45 minutes before he did, and that we’d meet up either at the “Little Pine Spring” iron trail sign, or at the next and more obvious landmark, Alexander Saddle. I mentioned that I’d be going pretty light on water (taking 1.5 liters), but I’d been as far as Little Pine Spring just this past April; it looked easy, just long. (See map.)

Rising at 4:00 a.m. in the sweet 51° degree seventh morning of this pseudo-epic trek, I boiled the last two tubes of Via instant coffee, ate a solid breakfast including dried eggs, and pulled my gear together marveling how light and tight the backpack had become. The map made the 11 miles out on the Santa Cruz Trail seem straightforward, and I over-confidently felt it would be easy to figure out since I have been to Santa Cruz three or four times in the past. Conant ‘09 bestows his “ideal” yellow color for the trail straight up from Santa Cruz Camp, then applies the less desirable purple color for the 5.6 mile trudge up along the “40 Mile Wall”; then past Little Pine Spring and the flat spot at Alexander Saddle, our second meeting spot. The last 4.7 miles would be all downhill across the front side of Little Pine Mountain and past old friend Nineteen Oaks Camp to Upper Oso.

On the seventh day about 7 a.m. I was charging hard and headstrong up the trail from Santa Cruz after crossing the murky and sulfurous creek, having chosen to bury my last foil meal (the contents only) and glad the backpack was light, around 34 pounds. After six days of backpacking and hiking, I felt strong as steel and light as a feather floating up the very rocky trail along the fancifully named 40 Mile Wall. The trail seemed to disappear, but we already knew that purple meant “may require some bushwhacking,” and I’d gone off trail more than once on the very sketchy descent to Coche.

There’s nothing like an overconfident, full-of-energy, aging Anglo baby boomer for being full of himself, and heedless of necessary mindfulness. When a correspondent pseudonymously named “Riceman” condemned a tent-site spot I’d picked during the “Search for Sacred Springs,” I had answered him stingingly, and haughtily stated that this guy “in fact has been safely backpacking since 1971.”

The Santa Cruz Trail seemed to disappear at the top of the 40 Mile Wall, and the map indeed shows a hairpin turn, basically a 160° southwestern turn (see red arrow on map with red letter “A”). Bushwhacking time for sure, and like Ajax I surged into the welter of Zaca fire destruction, interwoven young bay trees, willows, and thorny hard chaparral plants. I did not pause and think about waiting up for my hiking friend, whom I’d earlier spotted way down the line of the spectacular 40 Mile Wall, at least 45 minutes from my position.

Backpacking safely since 1971, I brashly pressed forward into the brush, after glancing at the Conant map again. As the very sketchy trail went deeper into the scrub and the big arroyo, I was continually able to find human boot prints ahead of me, as well as large bear prints. I never saw a trail on my right, but knew it had to be there and must be higher up. Heedless, I pushed on maniacally, glorying in my American-male energy and strong legs … after 90 minutes of this in the rising heat my fevered brain began to wonder.

But at worst, I felt, I could top out above the arroyo, see the Jeepway dirt road, cross over on top to Little Pine Mountain above Happy Hollow, >then find Chris at the Alexander Saddle spot.

In a kind of slow-motion horror, I realized how much time and energy I’d devoted to forcing my way up the very steep draw, or canyon, and that it was 1:30 p.m. and over six strenuous backpacking hours had already passed. Heat rising, water low. It was too steep to climb out on the canyon sides with a backpack on. In a moment of truth I began to go back down.

The burned earth, chips of talus, ankle-clinging vines, fire damage, downed trees, and hard chaparral made going back down even harder than the way up. Struggling desperately, quite thirsty, the revelation came: Return the many miles to Santa Cruz Camp because water is there. I had a plan, and didn’t feel disconsolate, but did feel rather tired. I knew my trusty friend would certainly call Santa Barbara County Search and Rescue (SAR), but there seemed to be no other option than to accept my error and return to Santa Cruz.

Still clambering down and searching for the return trail, from this higher vantage point I miraculously noticed a speck of pink plastic tag tied fairly high up on a tall bush. It was the hairpin turn in the Santa Cruz Trail to Alexander Saddle and Upper Oso that I had sped by much earlier.

I had to stop, check myself, ponder the options. Headstrong before, I’d be more careful with this choice: about 5.5 miles downhill to Santa Cruz; or about the same distance to get over Little Pine and then go to the truck at Oso, where Chris would be waiting. So, downhill back to Santa Cruz? Or a very tough 1.2 mile ascent to Alexander Saddle, then lots of down?

Experience and keeping notes sometimes help mitigate a backcountry blunder. During the “Search for Sacred Springs” backpack I’d carefully checked out the “spring” below Alexander Saddle, and there is a trough at that mangy spring which fills up with water and is used for horses. The water pipe goes down below the surface. I’d written earlier about “the trough’s scummy water surface,” and of course I remembered this unlovely source. Desperately thirsty, I pushed very hard to make the 1.2 miles ascent in the afternoon heat, got to Alexander Saddle, and found a note left there by Chris saying “Way Late! Calling SAR.”

I went on another mile or so and located the concealed turnoff to the trough, and promptly drank a half-liter of bad water from it, sitting on the trail, sprawled out on my sliced-up ensolite pad. I slowly sipped about two liters and packed another in my water bottle.

Within 45 minutes I was not only rejuvenated, but embarrassed by my rookie error: Never separate from your hiking buddy! And suddenly there was a helicopter overhead and two men with white helmets preparing to rappel down and haul me up.

Very quickly, I put on my backpack, laced up the boots, made a two-palms-together thank you signal and frantically waved them off while determinedly striding downhill toward Upper Oso. They were great. Santa Barbara County Search and Rescue is quite professional. They hovered about five minutes as I walked on gesturing constantly that I had water and everything was OK, even though the legs were a bit shaky from 11 hours on (and off) the trail.

If we are mindful of our actions, both mental and physical, we will enjoy the positives, of course, and embrace the difficulties our errors bring upon us in order to grow, as well as to avoid making them in the future.

I can excuse my missing the turnoff, particularly since we had been near a loudly rattling rattlesnake the day before and I was looking down in order not to step on one or fall down. But the truth is that I erred big time in separating from my hiking partner for so long, and again for not waiting for him when the confusion started. My mistake cost Chris considerable worry, as well as time. He did everything right and by the book, like the highly trained schoolteacher he is: He drove to the Paradise Fire Station and got the entire Santa Barbara County SAR team up and running. By around 5:30 p.m. these unpaid professionals were in the air and on the ground, searching for an experienced backpacker who had gone astray.

My arrogant assumption that I “knew” the trail was over 20 years out of date, and the 160° hairpin turn had become quite overgrown. Chris remembered finding it himself, and said later it’s like a tunnel, and you have to bull through it with your shoulders down, then after 30 yards of this jungle you are out in the open again.” I didn’t ever feel “lost” in a general sense since often I could see Old Man Mountain or a bit of Alexander Saddle: I knew in general where I was, but locating the old trail ruined by age, neglect, and the Zaca Fire eluded me.

I am grateful to Chris Caretto, a master camper and backcountry guru, not only for our 23-year friendship, but for acting very thoughtfully and professionally by calling in Search and Rescue right away. While I was crawling in the thicket, I knew help would come.

And many thanks to Santa Barbara County Search and Rescue. These are very cool people who come out to look for hubris-crazed backpackers in the San Raf Wilderness, among other locations. About a mile from Upper Oso I met a team of four SAR volunteers making their way up the Santa Cruz Trail to meet me. They gave me water (I had had enough from the scummy trough), and tried to relieve me of the backpack. With pathetic shreds of pride, I made it clear I’d come in with my shield or on it. They were gracious and just monitored my hiking progress.

Buddha stated, “There are two mistakes one can make along the road to truth … not going all the way, and not starting.”

In 1971, I was backpacking with my beloved life-partner on Little Pine Mountain. In 2012 I emerged from the San Rafael Wilderness on the same side of the mountain, drank disgusting water from a horse trough, waved off a rescue helicopter, and had to ponder my bullheaded blindness. I do not want to waste my own minor suffering, or the time and patience of several other good people (Chris and the Search and Rescue volunteers) by failing to face my mistake. Follow the rules: hike together; establish a firm meeting spot for backup; do not rely on old information since conditions on the ground change monthly.

Donations to support Santa Barbara County Search and Rescue can be made at sbcsar.org. This non-profit has highly trained unpaid professionals who go into the wild and into danger to help fools who lose their way; it is not supported by your taxes.

Addendum: On July 17, I made a 15-mile round trip trek to the 160-degree hairpin turn in the Santa Cruz Trail that I had missed. I attached more pink tags lower down in a few places, and hacked away at the overgrown vegetation which almost completely obscured this turnoff. My hope is that future backpackers coming up the 40-Mile Wall from Santa Cruz Camp will find it easier to locate.