Books sometimes remind me of numbers — sure they’re great, but there are too many of them! At The Santa Barbara Independent, the lifecycle of the typical volume submitted for review begins and ends in the same place: the mailroom. Below, tight rows of mail slots are crammed with announcements and cultural products; above, along a wide shelf at eye level, the rejected books and CDs rest in forlorn piles, having been brought back for one last look before they make their way into the permanent oblivion of donation or recycling. Sometimes, although not often — every few years sounds about right — a book, a CD, or a DVD rises up out of the detritus of our in-house remainder bin and, at the last possible moment, reasserts its claim on our editorial attention. In late November, deep in a post-Thanksgiving rut of early sunsets and late work hours, one such volume poked its head up out of the pile and called to me. There, at the bottom of the front cover of a rather bizarre pulp-fiction–looking paperback, was the following testimonial from James Ellroy, one of my favorite contemporary authors. “Brock Brower,” Ellroy wrote, “created a brilliantly observed and wholly synchronous work of art 40 years ago; now it is back to be savored and marveled at anew.” The Late Great Creature, first published in 1971 and now reissued in paperback by Overlook/Duckworth, purported to describe the making of a Roger Corman–style B movie, and to deliver a chilling, verbally pyrotechnic portrait of a fictional movie actor, the hugely talented and desperately weird horror star Simon Moro. Checking the back cover, I learned that Joan Didion liked it. So did Dan Wakefield, the New York Times, and Playboy. And there, in the last full sentence of the whole thing, was the clincher — “Brower lives in Carpinteria, California.” This local angle on an oddball ’70s novel about horror movies is what put The Late Great Creature in my briefcase, and what began my journey into the multiple fascinating worlds of Brock Brower: novelist, journalist, raconteur, and maybe the greatest rediscovered American novelist of the new century.

Hollywood, Horror Movies, and the Los Art of Long-Form Journalism

The author of The Late Great Creature turned out to be a man with impeccable credentials. A Dartmouth grad, Brower was born into New York media royalty. His father, Charles H. Brower, became president of the legendary advertising company BBDO in 1957 and was known at the height of the Mad Men era as “Madison Avenue’s favorite phrasemaker.” But it was in journalism that Charlie Brower’s son Brock distinguished himself. Brower was one of the most sought-after long-form profile specialists in the golden age of the New Journalism (up there with Tom Wolfe, Didion, and John Gregory Dunne) and employed by the top magazines in America to interview presidents, celebrities, and other top newsmakers. This was a time when such writers were not only routinely accorded ample space — 8,000 words was a typical minimum length for a feature — they were also actually paid well for it. Today’s print journalists, beset by the erosion of their audience and the acceleration of a Web-driven news cycle, can only wistfully imagine such halcyon days. In addition, Brower had gone on to become an innovative writer and producer for television at a time when that medium was at its peak, helping to create both the long-running newsmagazine 20/20 for ABC, and the classic 1980s educational science series 3-2-1 Contact for PBS.

But his book The Late Great Creature was clearly a very different affair. Yes, the narrator of the first section, Warner Williams, is a journalist, and in many ways a dead ringer for his creator, but what one encounters in the novel is not so much the high-flying world of a prominent member of the national media as it is a dark and twisted update of the lunatic universe of Edgar Allan Poe. Brower spent nearly a month on the set of Roger Corman’s film version of Poe’s poem “The Raven,” a film that starred Vincent Price, Peter Lorre, and Boris Karloff and featured a then-unknown actor named Jack Nicholson. He also populated his fictionalization of that experience with recognizable figures, from literary agent Candida Donadio to Esquire editor Harold Hayes and presidential candidate Richard Nixon.

Yoked to a sharp mind, powered by wide reading, and saturated with the acid-tinged psychedelia of the late ’60s, the prose of The Late Great Creature is unique. More knowingly “inside” than Thomas Pynchon, hipper even than Wolfe, and as scandalously obscene in places as the raunchiest Philip Roth, The Late Great Creature pulled me in like a sideshow barker and held me with the bony hand of a latter-day ancient mariner. Of all the great novels about the dark side of Hollywood — from Nathanael West’s apocalyptic The Day of the Locust and Budd Schulberg’s influential What Makes Sammy Run? to such distinguished and more recent contributions as Robert Stone’s Children of Light, Bret Easton Ellis’s Less Than Zero, Charlie Smith’s Chimney Rock, and Bruce Wagner’s I’m Losing You trilogy — The Late Great Creature is perhaps the best written, unquestionably the most literary, and often the downright creepiest. Brower has a gift for calibrating the proportions of horror, humor, historic detail, and pop surrealism in a way that makes this unlikely potion work. The novel’s dazzling verbal surface bursts with shocking moments of significant action. As the hero — if you could call him that — Simon Moro blends cynicism, ambition, and sheer perversity in an unforgettable way. When I asked Overlook Press publisher Peter Mayer to explain how it was that he discovered the book and what made him decide to rerelease it, he too expressed a kind of awe in the face of this indelible main character, writing that, “It’s a book that once read, has never been forgotten by those who’ve picked it up. Brower’s character, the aging star Simon Moro, is a tour de force, with his aspirations and his failures.” Mayer went on to say that it was his own original reading of the book back when it came out in 1971 that was behind his decision to publish it today, coupled with his belief that “every book is new to someone who hasn’t read it. … [The Late Great Creature is] a great read for a wide public because there’s so much movie lore embedded in the story. It tugs at the heart whilst we marvel as readers. It deserves to be read, and to be rediscovered in America.”

How Creepy Is It?

During the shooting of the book’s version of The Raven, Moro plays a series of increasingly morbid practical jokes on his fellow actors, and on the director and crew. These tricks are so outrageous that they frequently leave this reader wondering what Moro could possibly do next. Here’s an example: Dressed in a costume of black feathers as Ravenus, the monster protagonist of the film, Moro descends onto the lid of a coffin as he is filmed from above by a camera mounted on a crane for the type of shot ordinarily referred to as bird’s-eye view.

Then that hydraulic brake snapped, threw its pressure against the coffin lid, and dirt, pieces of spear, rot, decay, odor of death flung up at the buzzard camera. Worked wildly, smoothly enough to put Raven in line for an Academy Award nomination for special effects, though I doubt film will win any Oscars. Comes at you on screen a bit like an up-draft avalanche, until most of it falls back into coffin, close-up view now on Ravenus, a swerve-spin-swirl down, down, down into that fine and private place where none, I fear, do there em —

Brace yourselves, horror fans, take a good, close look at this shot sequence in Raven, and you will find, as we all did then and there, though admittedly without having to penetrate Terry’s additive mists and movie murk: M. is not alone.

At first I thought it was alive, even attacking him. The bone-white patina of the skull flashed at us, a lunge. But that was really M. pulling it closer to him, nuzzling into its upper vertebrae, then biting, lovingly, into its scapula with his great Ghoulgantuan teeth. Next I guess I realized how it was positioned: mounted on him, femurs extended at straddle, patellae squeezed to his sides, tibiae under his back. Final, great cinematic touch: Lenore’s necklace, with the silver arrowhead glinting right into the camera, wrapped round both their necks — or rather, his neck, its upper spinal column — for stark-shock visual image that leaves no question whom M.’s got in there with him between the winding sheets.

Ripped from its context, the passage may be a bit difficult to understand, so I’ll offer a hasty summary. In his ongoing battle to wrest control of the film from his director, Terry (the Roger Corman character), and from his costars, Moro has arranged for a skeleton to be hidden inside what is supposed to be an empty coffin. Thus, instead of getting the already macabre shot they had bargained for, the filmmakers instead receive an eyeful of Moro simultaneously making love to and devouring a skeleton, and not just any skeleton. Easily identified by her silver arrowhead necklace, this is supposed to be the dead body of the young girl who has, up until now, been his very much living co-star. It’s both a gruesome image entirely worthy of Brower’s great literary precursor, Poe, and yet another crafty punch thrown in the ongoing dispute over creative control that Brower locates at the heart of the collaborative art of filmmaking.

As with virtually every page of the novel, the passage teems with characteristic Brower-isms. There’s the reference to Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” poem, which, in this instance, is further complicated by his witty dis-enjambment of the syllable “em” from its natural position as part of “embrace.” And then there’s the terse, telegraphic style that borrows equally from the idioms of the journalist’s notebook and the screenwriter’s stage directions. Finally, the element of surprise serves as it does not only throughout the book but in the horror movie genre, as well, to both disturb and implicate the reader who can’t/must go on to find out what will happen next, and in the process would seem to encourage escalating levels of violent and deranged behavior. The Late Great Creature is the epic novelization that the great American horror movie almost didn’t get, a tribute to and an indictment of our most sensational collective impulses that marries the grand gestures of the silver screen to the ghoulish mise-en-scène of the graveyard. I was blown away by the book, and curious about its author. What would the creator of The Late Great Creature be like?

The Creature’s Creator at Home

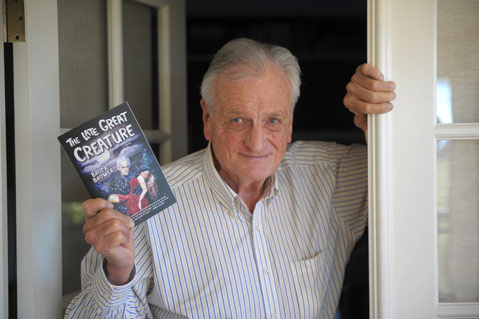

When I visited Brower in Carpinteria, he turned out to be a tall, handsome man with a full head of white hair who had just celebrated his 80th birthday. Brower recollected the fanfare that accompanied the original publication of his novel with a mixture of warmth and humor. “The National Book Award nomination was the work of [literary critic] Leslie Fiedler; he had the same fascination with freaks that I did,” he told me. “At the time, the so-called industrial celebrity complex was already well underway. I came off my assignment to cover the making of Corman’s Raven convinced that I could write up the horror movie genre as the key to this whole cultural phenomenon of unbridled narcissism that I had been witnessing as a journalist in Hollywood and in Washington.” As for the thesis of The Late Great Creature, Brower put it this way: “In our society, it doesn’t make any difference if you are a monster, as long as you’re an important monster.”

“I’m like a lot of writers who came of age in the 1950s,” he said. “While we were all excited by the opportunities that came our way out of the New Journalism, we still harbored this idea that the one way to legitimize oneself as a writer was to take the energy and techniques of journalism and use them to write a great novel. That’s what I tried to do with The Late Great Creature — justify journalism by transforming it into art.”

Toward the end of a delightful conversation full of mutual recognitions and spirited cultural analysis, Brower led me to a shelf in his study stocked with copies of a slim brown hardcover bearing the distinguished imprint of Boston publisher David R.Godine. This was Blue Dog, Green River, the novel that Brower published in 2005 at the age of 74. He inscribed it to me carefully, noting my name, the date, and the fact that it was given to a “welcome visitor, after my 80th.” I took it home and placed it alongside the other things in my stash of books I really want to read.

I finished Blue Dog, Green River last night. It’s totally different from The Late Great Creature. The protagonist is a heroic mutt, and the story is one of courage and redemption amid the whitewater rapids and Native American spirits of the great rivers of the American West. A deep reading of our collective dependence on water in this part of the world, it’s also a great adventure story and as thrilling to read as any popular suspense novel. In the ninth decade of a long life dedicated to writing, and in the shadow of an era that seems to promise the end of print’s long reign over the hearts and minds of thoughtful people, Brower, and the novels he has written, demonstrate that the lives of books, like those of the people who write them, are as unpredictable and potentially grand as any monster or spirit we can imagine.