Adrian Esparza’s Paño-rama at CAF

Exhibit Explores Notions Behind Prisoner’s Folk Art

This subtle, invigorating installation by El Paso-born, Cal Arts-trained artist Adrian Esparza mixes critical-theory concepts and folk-art forms into a single, elegant, and thought-provoking visual mash-up. Learning of his opportunity to show in Santa Barbara, Esparza began his associative process by researching the saint who gave our city its name. When he discovered that Barbara was celebrated for her martyrdom as a prisoner, the plight of gang members from Texas who are now federal inmates came to mind, and thus Esparza began piecing together the various elements that make up Paño-rama.

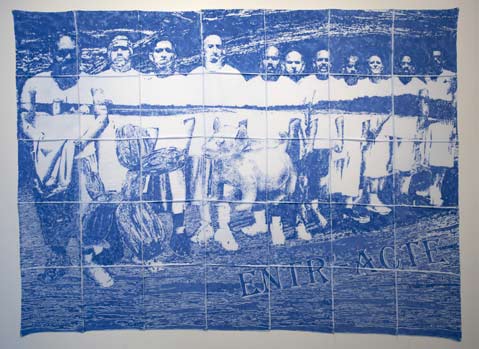

With a cousin incarcerated and a deep appreciation for the bitter paradoxes of a borderland upbringing, Esparza chose the prison art form of the paño as his initial point of departure. A paño is a simple white handkerchief that has been decorated with a pattern made by the repeated application of blue ballpoint pen or colored pencil to the fabric. Obscure in origin, the paño is common among Chicano inmates of the Southwest looking for a way to communicate with loved ones on the outside. These painstakingly fashioned images are mailed in ordinary envelopes, and their subject matter ranges from aggressive portraiture of gang members to seemingly light-hearted copies of images from popular culture, such as Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse.

A standard prison paño depicts a single image on a single handkerchief, but Esparza’s installation modifies the tradition by using grids of handkerchiefs to create larger, wall-sized images with multiple layers of meaning. Already, in this simple step a major part of the exhibit’s message is revealed, as the collective impact of this art form is greater than that of any individual instance. In addition to the three pieces made out of handkerchiefs—”Rebote/Handball (Santa Barbara),” “Hall-mark,” and “Photo-shop” (all 2010)—there is a fourth image on the Bloom Project walls, this one created out of blue rubber handballs of the type used by prisoners for their games. “Paño-rama,” the collage of handballs, further estranges and normalizes the mundane activities that allow these incarcerated men to fill their days.

The big images, so harsh in their literal reference to the experience of imprisonment, are rendered in a way that softens their impact, luring the viewer into an ambivalent space somewhere between aesthetic pleasure and social unease. Esparza has spoken in the past of his desire to articulate an art of acceptance, and to register through his work the importance of what he refers to as “the return to reality.” In this fascinating and suggestive installation, he’s come to a very strong and well-reasoned place.