Roberts Beats McCaw, $900,000 – $0

News-Press Owner to Appeal Arbitrator’s Ruling in Dispute with Former Editor

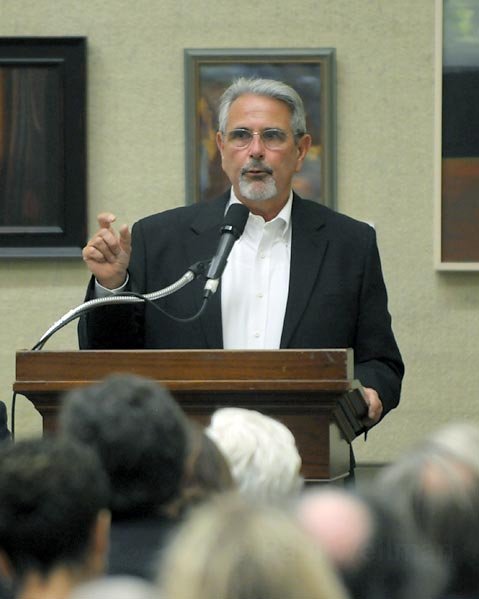

Ampersand Publishing, the parent company of the Santa Barbara News-Press, was ordered to pay roughly $915,000 in legal fees and arbitration costs to former News-Press editor Jerry Roberts in the wake of Roberts’ protracted contract dispute with that paper after his much publicized resignation in July 2006. Roberts quit — along with five other editors — during stormy and prolonged controversy over what they termed a breach of journalistic ethics by Ampersand owner Wendy McCaw.

Though this order was part of an arbitrated settlement that concluded in October 2009, the details were just released for the first time Friday, February 5, when attorneys for McCaw filed legal papers in Santa Barbara Superior Court to have the arbitrated ruling vacated.

From a strictly technical perspective, the ruling was a draw. The arbitrator, Deborah Rothman, rejected McCaw’s claims that Roberts had breached his contract by divulging confidential information about the management of the News-Press or that he has made defamatory remarks about McCaw and the paper. But she also rejected Roberts’ counterclaims that McCaw had effectively forced him to quit by making working conditions so impossible he had no other choice. Likewise, Rothman rejected Roberts’ contention that McCaw was legally responsible for a libelous blog authored by McCaw’s fiancé — and News-Press copublisher — Arthur Von Wiesenberger.

Even so, the arbitrator declared Roberts the prevailing party. As such, Roberts is entitled to recoup many legal costs from McCaw that he expended defending himself. To that end, Rothman ordered McCaw to pay Roberts $629,643.63 in legal fees. Roberts had expended $750,000 in attorneys’ bills. The arbitrator also ordered McCaw to pay Roberts $167,516 in arbitration costs.

Despite rejecting arguments for both sides, Rothman provided a detailed accounting of why she determined Roberts was the prevailing party. Ampersand’s stated litigation objective, Rothman said, was “to pin the blame on Roberts’ media statements for its lost prestige and credibility in the Santa Barbara community … Further, Ampersand pursued its objectives in this proceeding in a scorched-earth, take-no-prisoners, go-for-broke fashion … to punish Roberts for Ampersand’s public drubbing.” In this objective, Rothman concluded, McCaw had failed utterly to demonstrate Roberts had violated the terms of his confidentiality agreement with the News-Press or that he had defamed her in any way. She did acknowledge, however, that Roberts had spoken disparagingly of McCaw and the News-Press. “What Ampersand probably wishes Roberts had signed is a non-disparagement agreement. Ampersand cannot retroactively prevent Roberts from disparaging Mrs. McCaw or the News-Press.”

Rothman noted that it was McCaw, not Roberts, who initiated the legal dispute which, under the terms of Roberts’ contract with Ampersand, had to be resolved through mandatory arbitration. McCaw initially filed a $500,000 action against Roberts, but when he responded with a counterclaim, Rothman noted McCaw upped the ante by increasing her complaint against Roberts from $500,000 to $25 million. “I infer from the evidence before me that Mrs. McCaw is capable of great vindictiveness and appears to relish the opportunity to wield her considerable wealth and power in furtherance of what she believes to be a righteous cause,” Rothman declared in her ruling.

To that end, she noted that McCaw had spent $2.4 million employing up to eight attorneys — led by Barry Cappello — in her case against Roberts. By contrast, Rothman stated, Roberts had spent only $750,000, deploying a maximum of three attorneys at any one time. Rothman also accused McCaw’s legal team of delivering late hits and issuing unreasonable demands. In one stance, Rothman said, McCaw’s lawyers demanded compensation from Roberts seven times greater than the amount of the actual expenses incurred. In that matter — as in the entire case — Rothman declared McCaw was entitled to nothing.

Roberts’ legal team — led by attorney Andrine Smith — prevailed according to Rothman, because their stated litigation objective was to defend Roberts against every one of McCaw’s allegations, and they did so successfully. Rothman praised Roberts’ legal effort, stating, “Roberts’ successful defense against Ampersand’s legal juggernaut speaks to the skill employed by his small band of dedicated attorneys.”

IN THE BEGINNING: Rothman set the stage for the Roberts-McCaw donnybrook by providing a thumbnail sketch of the paper’s history over the past 10 years. In 2000, McCaw — described by Rothman as “complex, private, and principled” — purchased the News-Press from the New York Times. At that time, Rothman noted, McCaw made several public proclamations that as the newspaper’s new owner, she would not intrude in the news gathering or reporting process, but leave that to professionals. To the extent McCaw would inject her thoughts or feelings into the newspaper, she vowed, it would be through the paper’s editorial section. In 2002, the News-Press hired Jerry Roberts as editor in chief. Rothman described Roberts as “a conscientious and honorable journalist.” At the time, Roberts was a high-ranking editor employed by the San Francisco Chronicle. Prior to taking the Santa Barbara job, Roberts expressed his insistence that there be a total separation between the news reporting function of the paper and the editorial function of the paper.

For two years, everything went swimmingly, according to Rothman. In 2004, however, tensions between Roberts and McCaw flared. McCaw let it be known she wanted certain stories covered in the news relating to individuals with whom she was embroiled in legal disputes or involved romantically. In April 2006, Joe Cole resigned as publisher and was replaced by McCaw’s fiancé, Arthur Von Wiesenberger, a food and travel writer with no publishing experience.

In the summer of 2006, the News-Press erupted. First, McCaw penalized several writers and editors for violating a non-existing policy by publishing the address of a property that actor Rob Lowe had hoped to develop. Lowe and his neighbors were then engaged in a land use dispute over the size and scale of the proposed development.

McCaw insisted that henceforth no addresses would be published in the News-Press. In addition, she decreed that the word “blond” would be spelled with an “e” at the end, and that the names of women, when mentioned by the News-Press, would be preceded by the title Ms., Miss, or Mrs. Roberts was incensed. In his eyes, McCaw had not merely jumped the wall between editorial and news; she’d knocked it down. For her part, McCaw was incensed over the “us-them” political bias she thought they routinely displayed. In McCaw’s mind, her reporters failed to adequately represent the interests of animals and trees during controversies involving both.

In early July, McCaw appointed editorial page editor Travis Armstrong — long a lightning rod of intense controversy both inside and outside the News-Press offices — as publisher. She also gave him control of the newsroom. For Roberts, this was the last straw. There had long existed significant antagonism between Armstrong and the newsroom. Armstrong, for example, had written editorials critical of the paper’s news coverage, incensing many reporters in the process. But Armstrong came to personify the conflict between Church and State then engulfing the News-Press. Armstrong had been arrested driving the wrong way down a one-way street; police determined he was drunk at the time. The news section reported the incident, but when reporters attempted to write about Armstrong’s sentencing, the story was spiked over the objections of Roberts and the newsroom.

On July 6, Roberts tendered his resignation and was escorted from the News-Press building by Armstrong himself. The day before, three senior editors and longtime columnist Barney Brantingham had quit over the same issues. The meltdown was on. Since then, countless employees have left the News-Press as a direct result of this conflict.

It was Roberts’ belief that he was contractually entitled to six months severance pay. McCaw objected and filed a motion against Roberts claiming he’d breached his contract by releasing confidential materials and defaming McCaw personally. According to the arbitrator’s report, McCaw was especially incensed by an account of the News-Press troubles that appeared in The Independent‘s Angry Poodle column just one day after Roberts’ resignation. McCaw was convinced that Roberts was the source for much of the information contained in that account. That information, McCaw has contended, was confidential.

[By way of full disclosure, I am the author of that Angry Poodle column. As the author, I can attest that Roberts was not the source of any of the information contained in the offending column.]

Rothman concluded Ampersand failed to demonstrate that Roberts had been the source. Later, in the course of her 68-page opinion, Rothman would opine that the evidence indicated that Roberts was not, in fact, the source. But even if the facts were otherwise, Rothman concluded, none of the allegedly leaked information — or any of remarks Roberts made on the record at the time to many news outlets covering the strife — constituted confidential information.

To make her case, McCaw submitted numerous statements by Roberts lamenting the breakdown of journalistic ethics at the News-Press and the ensuing maelstrom of controversy. Among her exhibits — submitted to demonstrate Roberts’ breach of confidentiality — were such remarks as, “When they forced me out of the building, some of the staffers were trying to hug me,” or, “It’s a sad chapter for the paper and it’s sad for the community. How it turns out is anybody’s guess.” Of the 30 such comments attributed to Roberts — and provided by McCaw — to demonstrate Roberts’ contractual breach of loyalty, Rothman said, “Personal opinions and experiences cannot constitute protectable confidential business information.” To make her case, Rothman said, McCaw would have to demonstrate that Roberts released “technical data, financial data, specifications, formulas, processes, sales methods, supplier lists, advertiser lists, customer lists and books and records.” Failing that, Rothman said, McCaw had no case.

McCaw’s attorneys submitted at least 52 statements made during the heat of the crisis by Roberts to various news agencies that they contended were defamatory to McCaw. Most of these were remarks critical of McCaw’s increased involvement in decisions affecting the newsroom. Some of them were simple descriptions of having been escorted out of the building. Rothman concluded that many of the offending remarks cited by McCaw were factually accurate, and hence not subject to findings of defamation. Those that weren’t, Rothman noted, were expressions of opinion, and that under law, opinions are neither true nor false.

Describing McCaw as “a brilliant woman” but “a flawed witness,” Rothman concluded, “Her responses could be evidence of a profound lack of self-awareness, or a propensity to shade the truth for the purpose of garnering a large arbitration award.” Rothman stated some of McCaw’s remarks defied credibility. For example, Rothman cited McCaw’s exclamation, “Never,” when asked by Roberts’ attorney whether she had used the News-Press to punish personal or political enemies. Rothman stated that the unsigned front page news article the News-Press published indicating child pornography had been found on Roberts’ computer constituted evidence to the contrary. (For the record, police investigators said numerous News-Press employees other than Roberts had access to that computer; likewise, they said, other employees had that computer before. And finally, they suggested the computer disk in question may have been purchased secondhand by the News-Press, meaning that the images were present prior to the News-Press’s ownership. Roberts vehemently denied downloading the images.)

Rothman was struck by McCaw’s absolute certainty that Roberts was completely responsible for the serious loss of face the News-Press suffered as a result of the News-Press meltdown, and that McCaw herself has no responsibility for the paper’s woes. “How does one separate the self-inflicted damage to Ampersand, e.g. Mrs. McCaw’s arguably unpopular editorial stances … and running a front page article implying that he [Roberts] had downloaded child pornography onto his office computer, from any damage allegedly caused by Roberts … ?” she asked. “The evidence presented in this proceeding persuades me that such a determination would be near impossible.”

Rothman concluded that Roberts — in speaking out against the News-Press — acted in defense of “deeply held principles,” rather than any hope for financial gain. “The citizens of Santa Barbara had a right to know, even at the expense of Ampersand’s profits, that at least in Roberts’ eyes, journalistic standards that affected the quality of the paper were not being maintained.”

MCCAW VS. ROBERTS: If Rothman cast a skeptical eye on McCaw’s claims against Roberts, she was almost as dubious about Roberts’ against his former employer. In his counterclaim against Ampersand, Roberts contended McCaw had to have known he could not work with Travis Armstrong as publisher and that Armstrong’s appointment was tantamount to termination. Rothman conceded that if McCaw didn’t know this, she certainly should have given the bad blood between the two. But, Rothman concluded, Roberts never proved that Armstrong was appointed with the intention of making Roberts quit. And even if he had, Rothman added, it wouldn’t have made a difference. That’s because, she ruled, McCaw had plenty of grounds to terminate Roberts if she so chose.

McCaw, Rothman noted, was unhappy with Roberts for a host of reasons that could have led to his firing. Circulation was down on Roberts’ watch. Reporter bias remained an ongoing and unresolved problem, according to McCaw. And Roberts was not going along with a broader management program, hatched by McCaw and Von Wiesenberger. For example, he failed to provide a profile of Alyce Faye Eichelberger Cleese to Ampersand’s radio station, 1290 AM, as he’d been asked to. Likewise, Rothman stated, “Roberts failed to give sufficient coverage of new store openings, and of hotel ownership changing hands.” He spent $5,000 to have an out-of-town attorney lecture his newsroom on journalistic ethics, when the same information could have been provided for no cost. He insisted on loading up the column “The Dish” with insider politics as opposed to small town gossip, as McCaw and Von Wiesenberger had asked. “Any of the above examples of publisher dissatisfaction with Roberts’ performance, together with the disappointing circulation numbers achieved under his direction, even if not his fault, would have constituted legitimate cause for his termination,” Rothman wrote.

Ultimately, Rothman said, Roberts failed to recognize McCaw’s right — “as publisher of a relatively small town newspaper” — to control “the look, feel, and yes, slant of the paper.” Roberts failed to recognize he’d moved out of the big city media market, said Rothman, and moved into a smaller town environment where the rigorous divide between “church and state” may not be appropriate or enforceable given resource constraints and small town social realities.

Roberts also charged that he’d been personally defamed by a blog written by publisher Arthur Von Wiesenberger, allegorically comparing Roberts to the owner of a fictional hamburger stand who gives away free burgers, buys ethics awards, accepts bribes, makes false statements, and adds pork to his burgers in lieu of beef. Although Roberts was not named in the blog, Von Wiesenberger acknowledged that’s who he had in mind, and Rothman agreed anyone reading it would know he was the focus. Likewise, she agreed that the inaccurate allegations on the blog were libelous. But, Rothman dismissed Roberts’ defamation claim. Although she acknowledged there was a powerful circumstantial case to suggest Von Wiesenberger wrote the blog on McCaw’s behalf — Von Wiesenberger testified he cleared almost everything he did or wrote with her first — Rothman said Roberts failed to present clear and convincing that Von Wiesenberger was acting as an officer of the Ampersand corporation when he penned the blog. McCaw testified that she did not know of it in advance. Rothman noted that the blog on which Von Wiesenberger wrote the offending article preceded his employment with the News-Press, and even of McCaw’s ownership of it.

The arbitration dispute did not directly address, however, whether Roberts had been libeled by the News-Press reports that his work computer contained child pornography. That article engendered widespread community revulsion with the News-Press, even among individuals who were indifferent to the newsroom struggles to that point. Because the article in question did not appear in print until well after Roberts left the News-Press, it would not have been subject to arbitration. Though Roberts held a press conference angrily denouncing the article, he never filed a separate libel action. The News-Press never ran a retraction of the article, but it did publish a clarification. Roberts concluded that his chances of successful litigation were too iffy to proceed.

McCaw’s attorneys, Barry Cappello and Dugan Kelly, vowed to challenge the arbitrator’s ruling in court. “The News Press intends to take every step to reverse this miscarriage of justice and we have begun the process of petitioning the courts to vacate the award. It is a sad example of some of the abuses that can take place when parties are outside the actual court system,” said Cappello in an email. “Even more strangely she then ruled that even though Jerry Roberts lost his multi-million dollar claim against the New Press he, but not the News Press, was entitled to attorney fees. For Roberts to now chortle that it wasn’t about the “money” one must ask then why did he sue for millions of dollars in damages? Roberts lost and receives nothing.”

In past motions, Kelly and Cappelo challenged the arbitration process, claiming the arbitrator exceeded the proscribed deadlines in filing her report. Attorneys for Roberts concede the arbitration report was a long time coming, but stressed that Rothman deployed legal means to extended the time for deliberation, in part to allow additional briefings by both parties. Past efforts to invalidate the results by McCaw’s attorneys — using similar objections — have not succeeded, said Roberts’ attorney Andrine Smith. She expressed confidence they would not prevail again.

The matter is set for argument before Santa Barbara Superior Court Judge James Brown on March 24. Whatever he rules, it’s all but certain that his decision will be appealed.