Read the previous chapter here.

At 8:30 a.m. on February 17, 2007 – about seven-and-a-half hours after Jane Doe was allegedly raped, two hours after her return from the SART cottage – Santa Barbara County Sheriff’s Department Detective Daniel J. Kies rapped half a dozen times on her dorm room. Accompanied by Detective Michael Scherbarth, he waited 25 seconds for an answer that didn’t come, then used his cell to call her friend Krishna, who’d written her number on the witness report. She told him that Doe was expecting him and to try again but to call her back if Doe didn’t respond. Now Kies rapped harder, a dozen times, and waited 20 seconds for an answer before dialing Krishna and rapping another six times on Doe’s door. (Kies’s hidden voice recorder captured the entire encounter.)

Krishna at last let the sheriff’s deputies in, then went to rouse Doe. That took at least a minute. More than four minutes had passed since the first knock when Kies and Scherbarth entered Doe’s side of the suite.

Not quite a month before that day, the 32-year-old Kies had stood behind a podium at the Pacific Christian Church in Santa Maria, delivering an emotional eulogy to his 38-year-old brother Christopher Kies, a decorated Lompoc police officer and Marine veteran of the 1991 Gulf War, who’d been killed by an accidental overdose of medication prescribed after a 1998 on-duty motorcycle accident. The ceremony had followed a police motorcade from the Lompoc Police Department to the church, where Marines and police in dress uniform served as honor guards, while in Sacramento, by order of Governor Schwarzenegger, flags flew at half staff. Clearly, Detective Kies’s older brother had cast a giant shadow.

“Chris,” said Kies, “was a great cop who kicked ass.”

If that’s what made a “great cop,” then Kies entered Doe’s room on the path to greatness. As his words and actions over the next hours, weeks, and months suggested, kicking ass was what the somewhat-inexperienced lead detective, who had not yet taken the course in sexual assault investigations, might have intended from the moment he knocked on Jane Doe’s door.

Kies was probably still smarting from the untimely loss of his older brother. And he may possibly have been ‘roid raging, too, given his subsequent misdemeanor conviction for what appears to have been steroid use. That, anyway, is a reasonable assumption based on the type of diversion program he was assigned and the termination of his employment as a Santa Barbara County deputy sheriff in 2008, months after Eric’s conviction.

It was less a surprise to hear that Kies had lost his job than to learn that he’d kept his job and been subsequently promoted to detective after his conviction in 2002 – a year after joining the department – for violating California Penal Code section 148: interfering with a police officer in the line of duty. According to the incident report, Kies had begun the night at home with several Red Bull and vodkas before driving to a Guadalupe bar where his 10-year high-school reunion was being held. Drinks flowed, and by 10:30 p.m., he’d become so aggressive and belligerent that someone called for cops. The responding officer was approaching him when Kies suddenly lunged, shouted “Fuck you,” and grabbed the cop’s throat.

When he came to his senses in jail, Kies claimed he couldn’t remember anything about the incident. So at the very least, the lead detective in the case against Eric Frimpong had a special, if undeclared, sympathy for those, like Jane Doe, with alcohol-ravaged memories.

Doe was in bed when Kies and Scherbarth entered her room. Kies apologized. In an obviously sleepy voice she said, “It’s okay, I’m just tired.” Yet on the stand, Kies would testify that Doe’s eyes were red and glassy and her voice shaky not from being in a deep sleep – with a blood-alcohol level still nowhere near .00 – but from crying.

Seconds after they began talking, Kies recognized that the mark on Doe’s cheek, which she’d previously identified to Rivlin and the emergency-room doctor and the SART nurse and her friends as a hit mark, was, in fact, a bite. “That’s definitely, most definitely teeth marks, dude,” he said.

“That’s what she said,” Doe agreed, apparently referring to Wolfson. “As time goes by longer, I don’t know.”

Kies ignored the accuser’s tacit admission that her own memory was faulty. In fact, she suggested, the rapist might have hit her more than once; and later she said that being hit “was the part I remember for sure.” Even assuming that she’d been both hit and bitten, she remembered only one of the two and considered them to be mutually exclusive, meaning neither story could be considered reliable.

“We gotta find this guy,” Kies said. “He’s a, a piece of shit.” And he promised, “The motherfucker’s gonna go down.”

Near the end of the 35-minute interview, Scherbarth asked Doe again whether she recalled being bitten.

“It’s a full-on bite mark,” Kies insisted.

“I, I mean, I guess it’s all just like a big thing,” Doe said. “But, I mean, sure, if that’s what it looks like, I’m sure that it was, yeah. Yeah.”

From that point on, Doe would remember having been bitten, and describe it in ever more explicit terms, culminating at trial with, “[I]t felt like someone was sinking their teeth into my skin on my face and with a lot of force : [I]t was kind of like a second or so just biting as hard as he could : ” To other questions at trial – including who initiated going to the beach, and whether she walked on the beach and went up the Camino Pescadero stairs – she responded “I don’t remember” or “I don’t recall” or some variant more than 65 times.

* * *

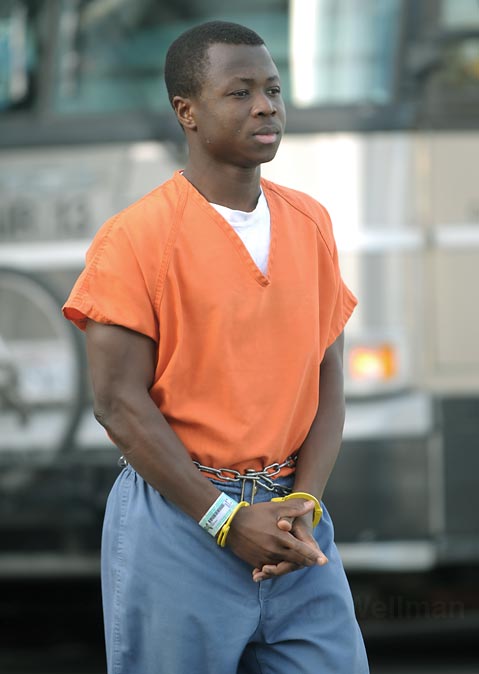

After taking Doe to have her face photographed and swabbed for DNA (none was found), Kies and Scherbarth began their search for the rapist in the homes along Del Playa, on the beach side. They eventually spotted a young black man who fit Doe’s description of Eric. He was playing ping-pong in Dolphin Park, next door to his house at 6547, with two other young men who would later be identified as roommate Josh Smith and next-door neighbor Nick Diebolt. But before approaching Eric, the deputies had peered into 6547’s back patio (through a hole in the fence, Kies claimed), where they spotted the beer pong table. Now they approached Eric. Kies switched on his Olympus WS-100 digital voice recorder, hidden on his person, its microphone apparently located near his mouth or chest.

“What’s up, guys?” Kies asked. “Do you guys live around here?”

Smith and Diebolt, both white, said they did. Where? asked Kies. Right there, Smith said, pointing next door.

Kies asked Eric if he lived with them, and when he said yes, Kies demanded his name.

“I’m Eric.”

Kies said he wanted to talk to Eric about “what happened last night.”

“Last night?” Eric asked.

“Yeah, you know what I’m talking about.”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know what I’m talking about?”

Eric asked him to explain.

“Um, well,” Kies said, “did you meet a girl last night?”

“A girl?”

“Did you meet a girl last night?”

“Mmm, no,” Eric said.

“No?”

“I met Krystal.”

“Krystal?”

“Yeah, she lives just a block from here.”

“You didn’t meet any other girls last night at all?” Kies said, and without waiting for an answer asked whether Eric minded “coming down to the station with us so I can talk to you about this?”

It’s odd that Kies didn’t bother to ask who Krystal was. Eric would have told him, as he did at the station, that Krystal Giang was a casual friend whose upstairs neighbor had given a party Eric attended. Then Eric would have described conversations with girls at two previous parties before meeting Doe (whose name he unfortunately did not remember) outside one of those parties, at 6681, and inviting her to play beer pong at his house, where he’d introduced her to his roommates.

If the phrase “meet a girl” wasn’t precise enough to elicit a thorough answer, that may have been the point for a detective who had already prejudged this “asshole” and “motherfucker.” Kies could not have known whether there was a relationship between Krystal and Doe – or whether “Krystal” was a nickname Doe had given herself. He could not have known if “a block from here” referred to the corner of Del Playa and Camino Pescadero. In fact, this detective with at least one admitted blackout himself could not have known whether Jane Doe had been badly mistaken; or perhaps wanted revenge on Eric for, say, spurning her advances; or was deflecting attention from the trouble she was likely to get in for being so illegally drunk; or was covering for an angry boyfriend who’d choked her and bitten her face after seeing her flirting.

“The victim was very clear who her assailant was,” Kies testified at trial, explaining why he considered the case closed after locating and then arresting Eric.

At the moment Kies asked Eric to accompany him to the sheriff’s station so that they could talk, this native of Ghana – a young democratic republic rife with corruption and cronyism – had never seen an episode of Law and Order, let alone spoken to a cop. He had no idea what his constitutional rights were.

“Sure,” he answered, even before Kies said, “You’d come voluntarily?” He believed he had no choice.

This, as Kies himself inadvertently implied at trial, was a valid conclusion. Asked by Sanger to explain what Eric told him that he considered incriminating enough to justify an official arrest, Kies noted that the suspect hadn’t given “me any side to his story other than his denials.”

But if Kies equated Eric’s failure to admit a crime with proof of guilt, why would he arrest his suspect after Eric described meeting Jane Doe and playing beer pong with her? Kies testified that Eric “did not refer to the victim or meeting the victim at any point in time, and the victim’s description was [sic], in my opinion, matched him perfectly after I got done speaking with him, and the fact that he denied or did not bring up meeting her at any point within that interview, I believed he was lying to me.” Sanger did not point out that the recorded interview contradicted this testimony.

When he formally arrested Eric, Kies admitted that he’d been “hiding stuff.” Hiding stuff may be considered within the bounds of legitimacy in interrogations, but not giving the suspect an opportunity to respond to direct allegations until after the arrest suggests that the motive for hiding stuff was to engineer a predestined outcome.

Kies never asked Eric: “Do you know a [Jane Doe]? She says she met you last night – and you raped her.”

Eric would have answered that he’d met Doe but certainly hadn’t, as Kies later phrased it, had “sex with her.”

Before leaving for the station with Eric, Kies told Smith and Diebolt that he’d “bring [Eric] back when we’re done with him.”

Smith inquired, “So, he doesn’t need any representation or anything, does he?”

“No, no,” Kies said.

“I’m just concerned,” Smith said, “because he’s from Ghana, so he doesn’t – he’s not gonna know the system as well.”

“I’ll explain if it comes necessary,” Kies said. “I’ll explain every right he has. I have to explain it.”

Smith tried to ask something else, but Kies, as he would throughout Eric’s interview at the station, talked over him; and with the recorder’s microphone located on Kies’s body, only Kies’s voice can be heard clearly. So on the transcript of the conversation, Smith’s words here, and Eric’s in dozens of places during his own 45-minute interview, are memorialized as “[unintelligible]”, falsely conveying the impression to readers, like the jury, that Eric had mumbled or stopped speaking when in fact he’d been interrupted.

Eric climbed into the car with Kies and Sergeant Ross Ruth, who’d parked on the street. The ride to the station took about 15 minutes. Once inside, Eric was led into a room with Kies and Scherbarth. He answered Kies’s circumspect questions, noting that he’d spent part of the previous late afternoon playing volleyball on the beach, then came home to nap and shower before venturing out to some parties, one of which was at 6681 Del Playa. He explained that nearly everywhere he went, students recognized him as having been a star of the national championship soccer team, and that his fame was the reason he received invitations to parties others couldn’t get into.

He was, in short, an Isla Vista celebrity. No wonder. The win against UCLA two months before to take the national championship had been only the second in UCSB’s athletic history, 27 years after the men’s water polo trophy. It was major news in town, avoidable only by intention, as the victorious team was given two parades, including one that trailed out of the school and through the streets of Isla Vista, concluding with a nightlong party on the beach.

Asked by Kies about Krystal, Eric said, “Oh, even before that, one of those random, like, friends : started talking about beer pong, and one of them wanted to play beer pong, and I – you know, we have a beer pong at our place.”

Eric then referred to a “guy” who was with the girl, “talking to one of his friends in front of our house, and that girl wanted to play the beer pong, so we played for just like, I think, 12 or 13 minutes.”

Kies, for some reason, did not inquire about “the guy.” He asked Eric to describe the “girl,” which Eric did poorly, unable to express whether Doe, a black-haired Eurasian, had black or blond hair – in part, Eric explains, because she was wearing a knit cap, a fact Doe’s friend Krishna confirmed at trial.

Kies asked whether Eric remembered everything he had done the night before. When Eric said yes, Kies requested – and Eric granted – signed permission to send someone to retrieve the clothes Eric had worn.

“Describe them to me,” Kies said of the clothes. Eric said they were black jeans and a long-sleeve striped shirt. Kies insisted he wanted to “clear this up so I can – I need to see the clothes that you were wearing last night, and if I can clear this up and see if they match then – or don’t match – then maybe we can clear this up.”

Kies already knew that Eric matched Jane Doe’s general physical description and spoke with an accent. He already knew that Eric had introduced her to his roommates. He already knew that Eric had a beer pong table and they’d played together. And he knew that Doe had been unable to identify anything Eric had worn – which suggests that Kies was trying to con the suspect.

By tacitly implying that this might be a simple case of mistaken identify, easily rectified, the detective would get to confiscate clothing he presumably believed had been stained with DNA. Maybe it didn’t occur to the detective who considered Eric’s denials to be self-incriminating that a guilty man would decline permission precisely because of the DNA. Or maybe Kies considered Eric too ignorant to know better.

When Eric said he didn’t understand “what is going on,” Kies at last said he was “going to come up straight and honest with you,” and explained that there was a “girl who made a report” about meeting Eric, going to his house, being introduced to his roommates, playing beer pong, and walking down to the beach for “sex.”

“Wow,” Eric responded.

“Do you remember that?” Kies asked. It was a question that presumed guilt, as opposed to, “Did you do that?” or, “Is that true?”

“No, no.”

“So do you – do you think I have the wrong guy?”

“Yeah.”

“You think I got the wrong guy?”

“I seriously don’t know about the beach,” Eric said, meaning he concurred with the story right up to the part about the beach and the sex.

Kies and Scherbarth whispered for several seconds before a nearly four-minute gap that preceded Kies’s return, upon which he informed Eric he was being “detained.” Kies read the Miranda warning, then added, “Having these rights in mind, do you still wish to talk to me? No? Okay. Um, all right.”

For some reason, Eric’s refusal flabbergasted the detective. “What I want to do then is, um, I’m gonna go ahead and – uh, oh, shit,” Kies said. “Let me think.”

Think about what? Police procedure is clear when a suspect unambiguously invokes his right to silence, as Eric had: stop questioning, stop badgering, stop cajoling.

The jury did not hear Detective Kies’s outburst or any of the ensuing 12 minutes that included Kies’s repeated attempts to convince Eric how it was in his best interests to keep talking. Nor did they hear Eric’s repeated denials, which he began making in response to the direct accusation.

Prosecutor Barron argued, and Judge Hill agreed – possibly with foreknowledge that Eric would not be taking the stand, something neither Eric nor the Monahans knew at the time – that the recording of the police interview as an exhibit should be truncated to only the first 37 minutes, stopped at the point where Eric was formally arrested and read his Miranda rights. So the jury did not hear Eric’s insistent denials of guilt.

This opened the door for Barron, in her closing argument, to brazenly claim that Eric had “no alibi” – a statement both unconstitutional (the burden of proof is on the state, and defendants are not required to say a word) and shameful. After all, it was she who had argued to exclude the rest of the recording. And at the time she uttered the words she knew from his name appearing on the defense witness list that there was indeed an alibi witness. How ironic that in the same closing argument Barron accused Eric of spinning a “web of lies.”

Just after Kies’s “oh, shit” moment, there’s a break in the recording. Though the transcript reads as a continuous document (with “pause in recording” noted), the interview itself was broken into four separate digital audio files, indicating manual stops and starts, which Kies himself transferred onto his home computer before burning them all onto single CD. I sent these files to BEK TEK, a Virginia company of former FBI agents considered to be among the country’s leading audio and acoustic experts, and asked whether the files might have been doctored. They had not, it appears. But the company’s report corroborates what Eric claimed all along, and what his syntax in several places indicates.

Between the 43-minute first file and the three-minute second file is an interval of 50 seconds during which Eric told Scherbarth that he was confused. This is confirmed by what Kies told Eric upon his return: “My partner said you weren’t clear as to what’s going on.”

Eric reiterated that he was confused. Kies responded by explaining Doe’s allegations in plain language: “You guys played some beer pong, then went for a walk down to the beach. You threw her down and, um, raped her.”

“Really?” Eric said.

“That’s what she said,” Kies said. “Yeah. So, that’s why you’re here. That’s why you’re being arrested.”

Kies had just admitted that Jane Doe’s description and accusation were by themselves enough for an arrest. If every law enforcement officer acted as he did that day, all that would be necessary to have your nasty neighbor arrested would be a credible story about how he inflicted your scratches and bruises, the ones you actually got from falling down drunk or fighting with your drunken boyfriend. And your neighbor’s denials, according to Kies’s logic, would be confirmation of guilt.

While Kies may have been acting within his prerogatives as a detective, his failure to consider alternatives based on what Eric told him about another “guy” being present – a contention made more credible by Eric’s eagerness to hand over his clothing for inspection – foreclosed the possibility of an authentic investigation. And that failure became all the more unjustifiable given what happened during the one hour and 44 minutes between the recording of the second audio file and the third.

In that interval, Eric was booked, photographed, fingerprinted, and swabbed orally for DNA, then taken into an adjoining interrogation room by Sgt. Ruth and Detective Scherbarth, who may have been trying to play good cop to Kies’s bad cop. Intended or not, it worked. Explaining that he felt comfortable with them and believing they wanted to pursue the truth, Eric told them how and where he’d met Jane Doe, how long they’d played beer pong, that she’d wanted to smoke a cigarette and so they’d gone next door to Dolphin Park. He left nothing out, including where they’d been walking on Del Playa when “that guy” called Jane Doe at 11:44 p.m. before suddenly showing up and following them to Eric’s, at which point Doe ordered the “guy” to get lost. But the guy didn’t leave, Eric told the two deputies. He said that as they played he glanced down the darkened walkway along the side of his house and noticed “the guy” standing out front on Del Playa.

The significance of the detectives’ failure to act on Eric’s claim that another male was present cannot be overstated. As would come to light in 10 days, that “guy” was Benjamin Randall, a freshman who lived in the Tropicana dorm while attending Santa Barbara City College. He had spent most of the evening with Doe at their common friends’ parties. And it was his DNA, not Eric’s, that would be discovered in her panties.

There is no evidence that Randall attacked Jane Doe. But if he’d been the assailant, a possibility that the District Attorney’s office entertained before trial, then the detectives’ disregard of Eric’s references to “that guy” prevented them from possibly finding any defensive wounds caused by Doe’s fighting back, the kind she believed she’d inflicted on her attacker and the kind not found on Eric. They would have healed on Randall in those days before he chose to surface.

One has to wonder whether Scherbarth and Ruth recorded or videotaped Eric’s interview with them in the expectation that he would confess to the “good cops.” Before Sgt. Ruth knew which particular case his telephone caller was referring to one day, he told Oscar Rothenberg that all interviews are videotaped unless that room is otherwise in use. And since only audio exists of the interview recorded by Kies himself, it’s logical to infer that the room with the videotaping capabilities was the second one into which Ruth and Scherbarth took Eric.

So where’s the tape or DVD of his interview? Maybe the equipment was on the fritz that day. If so, where’s the written report required to have been filed by Scherbarth or Ruth about their contact with Eric?

This might have been an appropriate line of questioning for Sanger to take when the detectives testified at trial. Paul Monahan had long ago told the attorney that, at 1:50 p.m. on the day of Eric’s arrest, Ruth had called Monahan and left a voicemail message (preserved by Monahan): “I’m here with Eric who wanted to let you know that we are with him right now and we are talking with him. If you could please return my call at : “

Monahan had called back moments later and asked Ruth whether Eric was under arrest. Ruth said no. He explained that in order to “clear” Eric as a suspect in a crime, they needed consent to swab his genitals in a search for Doe’s DNA. What Ruth didn’t add, still concealing Eric’s arrest, was that they had already swabbed his mouth – but that without signed consent, the sheriff’s deputies would be forced to obtain a court order before calling in the SART nurse for a genital swabbing. This being a Saturday, the process could easily have taken more than a day, by which time any DNA might be eroded by clothing, washed away, or otherwise rendered unusable.

Before handing Eric his phone, Ruth assured Monahan that they would not be recorded. Eric then explained to Monahan that a young woman had filed charges against him for sexually assaulting her. (Of all the detectives in this case, only Ruth wasn’t called by Mary Barron to testify. Why he wasn’t, though he appeared on the prosecution’s witness list, is something else Sanger might have asked.) Monahan instructed Eric to respond either yes or no to the question of whether they’d had sex.

“No,” Eric said adamantly.

Hearing that, Monahan clarified whether Eric understood what the detectives wanted from him, pointing out that if her DNA was discovered on him, he would go to prison. Eric repeated, “I did not have sex with the girl.” Now Monahan told him to go ahead and sign the consent form, both of them believing the results would clear Eric.

Scherbarth led Eric back into the first room, and Kies soon appeared, asking for permission to ask Eric some more questions. Eric granted it.

“If you did something that you’re scared of or you’re embarrassed, or maybe because you have a girlfriend and you ended up having sex with a girl last night that’s not your girlfriend, just tell me that, okay?” Kies said.

“No, I’m not,” said Eric. “I’m not worried about that at all.”

“You’re not worried about that at all? Okay.”

“See, the thing is, I know you guys are going to find out the truth : I didn’t have sex with her.”

“Okay, do you – do you know what girl I’m talking about now? Because earlier – ” (Kies’s written report of the interview refers to another young woman with whom Eric had played beer pong “earlier” in the evening. If he actually believed that, it can be taken as proof that he was both a poor questioner and poor listener.)

Frustrated, Eric interrupted him. “I didn’t have sex with her,” Eric insisted. “They” – meaning Scherbarth and Ruth – “they just asked me, ‘Did you have sex with her?’ And I said, ‘I didn’t have sex with her.’ I didn’t mean, like – “

Kies talked over him, and now Eric had had enough. He suggested that they just get on with whatever was going to happen.

“You told them to go get your clothes?” Kies asked, confirming what Eric had said to the other detectives.

“Sure.”

“You’ll go with us to get your clothes and stuff? Okay, let us in your room, show us the shirt and the pants and the underwear that you were wearing last night?”

Eric accompanied them to his house. The detectives took his shirt and jeans from the room he shared with Pat and another roommate, both of them surfers who kept their boards and wetsuits on the adjoining deck. The floor itself was deep with months’ worth of sand from their feet, boards, and suits. Scherbarth, who forgot to bring a camera in order to photograph the room and clothing, checked Eric’s shoes and, finding no sand inside, left them behind. He would later note that he found some grams of sand in the cuffs of Eric’s jeans. Just one discrepancy: Eric never wore cuffs.

Read the following chapter here.