Bouncing Baby Marsupials

Pouched Mammals Kicked All Others Out of Australia

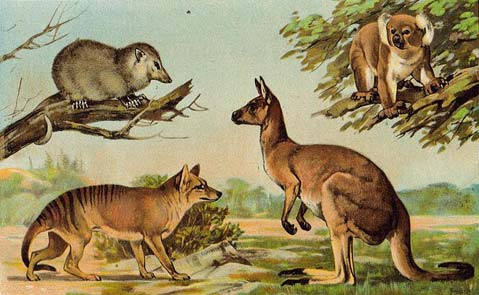

If you’ve seen a kangaroo at the zoo, or wanted to hug a furry koala, or missed an opossum scurrying across the road in front of your car at night, then you’ve had a run-in with the strange group of mammals called marsupials.

As most know from the kangaroo, marsupials are distinct from placental mammals in that marsupials possess a pouch, or marsupium.

However, only about half of marsupials actually have a permanent pouch, and these vary between families. Pouches are most developed in tree-dwelling, burrowing, or jumping species, accommodating the bouncing and jostling the baby must endure. A few marsupials – bandicoots and koalas – have a placenta instead of a marsupium, but it is very different from the placentas of placental mammals, providing less in the way of nutrients to the fetus and forming a weaker connection. Despite these exceptions, the names “marsupials” and “placental mammals” have stuck.

Marsupials and mammals have enough ancestors in common to make marsupials seem quite similar to us, but the two groups are actually separated by millions of years. The two parted evolutionary ways toward the end of the age of the dinosaurs, in the late Cretaceous era, 90 million to 65 million years ago. The most recent theory, based on fossil records, is that marsupials originated in China.

In the late Cretaceous, many continents were connected that have since drifted apart. Marsupials may have migrated westward through Europe to North America, down through South America, then to Australia from Antarctica, which were connected. Soon after marsupials arrived, Australia and Antarctica split apart, isolating marsupials from the world. They pushed out the few existing placental mammals, flourishing and diversifying for 65 million years. Placental mammals drove most marsupials to extinction in Europe and North America 20 million years ago, although some still exist in the Americas. Today, more than 300 marsupial species are alive, almost all in Australasia, which includes Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, and the surrounding islands.

The millions of years of evolution separating marsupials and placental mammals created many differences between the two groups, the biggest being how they raise their young. Marsupials have a shorter pregnancy, and are born at a much earlier developmental stage than placental young, due to weaker connections between the fetus in the uterus and the marsupial mother. When born, the immature young climb to the pouch, where they attach to a nipple and develop for weeks until mature. While the body is mostly undeveloped when born, the young have well developed muscular, clawed forearms to help them climb to the pouch. Once mature, they leave the pouch for short periods but still return for warmth and protection.

Consequently, marsupials trade a small investment in their young before birth for a great investment afterward due to a prolonged lactation period, resulting in a total investment in mature progeny that is similar to that of placental mammals. Basically, the difference can be thought of as trading an umbilical chord for a nipple.

There are other differences between placental mammals and marsupials, many being useful adaptations in the Australasia climate. Marsupials have lower metabolic rates, making them less active but better prepared to deal with the Australian deserts. The latter is also addressed by most being nocturnal. Other noteworthy anatomical differences: Marsupials have different reproductive organs, with females having two vaginas and males with accommodating parts; and they have distinctive dental structure.

Additionally, marsupials don’t have the same degree of diversity as placental mammals; there are no marine, true flying, or hoofed marsupials. This may be due to the short time spent in the uterus and requirement for early developed, clawed forearms to reach the pouch; specialized limbs, such as wings or fins, may be impossible.

Despite such differences, many parallels between marsupials and placental mammals can easily be drawn.

There are many shrew-, rat-, and mouse-like marsupials, including many opossums. North of Mexico, the only existing marsupial species is the Virginia opossum; like it, many marsupials in dense South American forests developed prehensile tails, like those of monkeys in South American forests.

The numbat, or banded anteater, tears open anthills, licking out the bugs with a long, sticky tongue, resembling anteaters found continents away.

Many larger, primarily herbivorous marsupials – including koalas, wombats, and kangaroos, with adaptive climbing, burrowing, or jumping digits – fill a similar ecological niche similar to grazing hoofed mammals.

While no true flying marsupials exist, there are many gliders, including the tiny sugar glider, a commonly sold pet in many states.

There are also two species of marsupial moles that are blind, have a leathery nasal shield, and leave no tunnel behind them.

While all large marsupial carnivores have become recently extinct, many once existed with similar placental cousins. The Tasmanian wolf (Thylacinus cynocephalus) became extinct in 1936, the last one dying in Australia’s Hobart Zoo, after being hunted by European settlers. Many similar species have been found in fossil records. A marsupial similar to the North American saber-toothed tiger, the extinct Thylacosmilus atrox, would have been quite a formidable predator to stumble upon.

The smallest marsupial has the honor of being a carnivore; at 2.3 inches and 4.2 grams, the terrifying long-tailed Planigale strikes fear into the hearts of many insects. The Tasmanian devil, at the size of a small dog, is the largest existing marsupial carnivore. It has recently become endangered and is feared to become extinct as populations are being ravaged by a strange transmissible cancer, devil facial tumor disease.

While humankind has brought about the extinction of many marsupials, many still exist for us to learn about and, through them, about our own mammalian past. Great conservation efforts are needed to ensure their survival so that generations to come can get to know our strange cousins from down under.

Biology Bytes author Teisha Rowland is a science writer, blogger at All Things Stem Cell, and graduate student in molecular, cellular, and developmental biology at UCSB, where she studies stem cells. Send any ideas for future columns to her at science@independent.com.