The Men Behind the Myths

From Argentine Cowboys to Tossed Tortillas, the True Story of UCSB's Mascot

In the picturesque riverside town of San Antonio de Areco, Argentina, a leathery man leans against a wire fence, overlooking a horse-riding ring the size of several football fields. His chambergo, a flattish wide-brimmed sombrero, is tied under his neck with a leather cord, nearly hiding his blue eyes from view. He wears a bushy mustache and a neckerchief, and tucks his fac³n, a long silver-handled knife, into his silver-studded rastra belt, which holds the blade flat against the small of his back. Covering his legs are grey bombachas, baggy around the thighs and tapered at the ankles to fit into his boots. This afternoon, he’s already shed those boots in favor of a snug pair of country slippers called alpargatas. He’s most content to sip yerba mate, the hot bitter herbal drink used to fend off hunger and fatigue, and strum his guitar, as the fictional hero Mart-n Fierro would have done.

The man is a gaucho, and-like his compatriots spread across the pampas, or grasslands, of South America, from southern Brazil to the remotest corner of Patagonia-he reflects the dusty romantic glow of his American cowboy cousins. When Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid fled the United States more than 100 years ago to settle in southern Argentina, what they found was an almost prehistoric version of the cowboy, men who resolved disputes not with a gun, but with a knife, who valued independence almost as much as style, and whose horse-riding skills could rival the best of the Wild West.

For more than 400 years, these men have ridden the empty countryside. Initially, the gaucho was regarded as nothing but a mounted savage who hunted free-roaming cattle. As his reputation as an indomitable free spirit with a fiery temper grew, landowners and the government increasingly found it necessary to domesticate the gaucho by keeping him occupied with paid work on vast ranches. Today, the gauchos as Butch and Sundance found them are practically extinct. But much like American cowboys, the gaucho legend continues to grow even as their sheer numbers dwindle.

One of the quirkiest parts of the gaucho legacy lives in our corner of California, where students, alumni, and sports teams from the University of California at Santa Barbara call themselves The Gauchos. But even though UCSB took Gauchos as its nickname more than 70 years ago – and thousands of alumni are expected to return this weekend to celebrate the 3rd annual All Gaucho Reunion – few in Santa Barbara know just what a gaucho is, or why they should be proud to wear that name. And fewer still know how the gaucho name came to be immortalized here.

It’s time to set the record straight. This is the true story of the gaucho, from Argentine cowboy to UCSB mascot.

Hello, Gaucho!

On the rich, green grass of the competition ring beside the R-o Areco, teenage gauchos are riding buck-wild colts. After being thrown by the horse or scooped from their mounts by grown-ups before things get ugly, they limp to the sidelines and smile at their friends, who are sharing beer and cigarettes. As the public address announcer celebrates San Antonio de Areco-“The town that knows tradition”-a yell goes up from the makeshift horse racing strip beyond the ring. A rider taunts his younger opponent as he leaves him in the dust, causing the crowd to erupt in enthusiastic cheers.

This is just one scene that I witnessed two years ago during the annual Fiesta de la Tradici³n, which will celebrate its 70th anniversary in 2009. About a 90-minute drive from Buenos Aires, this is where an ever-diminishing number of real-life gauchos and gaucho enthusiasts gather to celebrate hundreds of years of tradition on the Argentine plains each November. Together, they pay homage to the free will, love for drink, and unmatched skill in horsemanship that has made the gaucho a historical icon, celebrated by everyone from Jorge Luis Borges to Charles Darwin.

No one knows for certain the origin of the word “gaucho,” and no two descriptions are identical. The word has no less than 35 possible origins, including the Brazilian Portuguese guadeiro (“vagabond”), the Guaran- Indian ca’ °cho (“drinker”), and the Latin bagaudae (“thieves”). In 1826, a British businessman called them “little better than a carnivorous baboon,” but then, just 100 years later, the already broken and domesticated gaucho was romanticized in the 1926 novel Don Segundo Sombra by Ricardo G¼iraldes: “For action, he loved perpetual wandering over all else, and for conversation, soliloquy.”

What is known is that the original gauchos were an ethnic mix of Guaran- and Mapuche Indians and Portuguese and Spanish colonials. Failed 16th century attempts to found the city of Buenos Aires left horses and cattle roaming and thriving on the pampas. If a gaucho had a horse, he could support himself, travel, and have plenty of time for vicios (vices), all without having to listen much to anybody.

On his horse, the gaucho became more than an ordinary man. Darwin marveled at the gaucho’s devotion to style, noting, “The gaucho never appears to exert any muscular force.” Suave and astounding physical displays-true gauchos can land on their feet even when their horses crash violently to the ground-went hand-in-hand with the “absolute indifference toward the facts” made popular by Don Segundo Sombra, the title character of G¼iraldes’s novel. When Segundo Sombra sits down to eat in a cantina, he doesn’t, under any circumstances, ask to see the menu-his only gesture is to grumble, “Bring us whatever you got.”

The gaucho’s penchant for drinking and gambling, and his fondness for resolving subsequent arguments with his knife, earned him a reputation as a menace to civil order. Large landowners and the government alike sought to rein in the gaucho’s freewheeling spirit, and by the end of the 19th century, the gaucho was limited to choosing between killing Indians for the government-the same Indians from which he had descended-or shoveling shit for a big-shot rancher.

As such, true gauchos are hard to find today, yet popular culture refuses to let them die. In Argentina, for instance, the annual television awards are named the Mart-n Fierros, an homage to the title character in Jose Hern¡ndez’s epic gaucho poem. And for 21st-century Californians, no modern incarnation of the gaucho is a prominent as UCSB’s nickname, especially as the university’s teams continue to succeed in multiple sports across the country.

A New Home on the Range

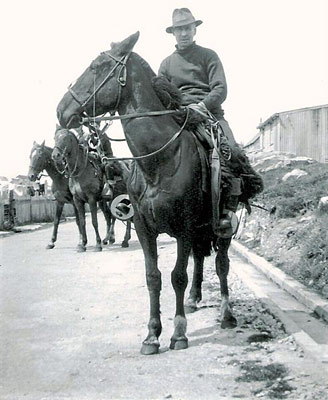

For the incoming UCSB student, few questions are as prominent as, “What’s a Gaucho?” The university has been using the nickname since 1936 when, inspired by Douglas Fairbanks’s performance in the 1927 film The Gaucho, the female student population led a vote to change the mascot from the original Roadrunners.

Santa Barbara resident Bob Lorden graduated a Gaucho from the Santa Barbara College of the University of California in 1949, when the campus was still located on the Riviera. His older brother had been a Roadrunner. Lorden agreed that the film had been an influence on the name change, but he also recalls football coach Spud Harder being eager to drop the wimpy Roadrunners name and the student body wanting a Spanish name along the lines of the celebrated Dons of Santa Barbara High School.

“Later, the students tried to change the name from Gauchos because they felt Argentina was too far from Santa Barbara,” Borden recalled. “They came up with several names, but none ever surpassed Gaucho.”

By the late 1980s, UCSB had more fully embraced the gaucho. Fans attending standing-room-only basketball games were swinging blue-and-gold boleadoras over their heads to rally the team; these were foam and yarn representations of the rock-hard leather balls that gauchos tied to a cord and used as weapons to hunt rheas, a flightless South American ostrich-like bird. Meanwhile, “Gaucho Joe”-the all-American boy famous for psyching up UCSB basketball crowds in the program’s 1980s heyday-ran around the Thunderdome in white jeans and a Batman muscle T-shirt, yelling like crazy.

In the mid-1990s, Gaucho basketball fans became nationally notorious for chucking tortillas onto the court at televised games. Though tortillas fly well, they are virtually unknown in Argentina, where they’re instead sold under the name rapiditas (or “quickies”). The tortilla barrages often stopped play on the court and resulted in technical foul calls against the Gauchos. Coaches could occasionally be seen begging the crowd to stop and even helping with cleanup. (They should have taken solace, at least, that the crowd hadn’t thrown bloody sirloin steaks or globs of dulce de leche, a thick caramel dessert, which are, in fact, two quintessential Argentine flavors.) The practice peaked in February 1997 when the Gauchos took on University of the Pacific in a game that was televised on ESPN. So many tortillas were thrown by the rowdy fans throughout the game that UCSB coach Jerry Pimm was eventually ejected. While the UCSB Athletic Department now prohibits tortilla chucking at basketball games due to the problems that moist bits of dough create on a hardwood athletic surface, the Gaucho tradition persists at soccer games.

Shortly after Tortillagate, the UCSB Athletics Department changed its look and scrapped its longtime logo, a blue silhouette of a horseman swinging boleadoras. Instead, UCSB launched the current logo: a body-less head with wide-brimmed hat and Zorro-like mask-a dead ringer, at least in the eyes of assistant athletic director Bill Mahoney, for McDonald’s Hamburglar. Wearing a mask and cape in those days was the Fantom of the Dome, Aaron Bishop, who fired up crowds and embarrassed referees with uniquely energetic skits, crowd-pleasing chants, and the occasional rubber chicken. (Speaking of the rubber chicken, one of my friends once snatched it out of thin air as it whizzed past during a game at the Thunderdome, a heady moment he counts as one of his college highlights.)

After years of watching increasingly raucous crowds in the UCSB arena, Mahoney nicknamed the place “The Thunderdome,” a nod to the Mel Gibson film Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome. In so doing, the assistant A.D. unintentionally evoked the Argentine gaucho better than perhaps any previous attempt at UCSB because the film’s protagonist is an inveterate wanderer who carries his few possessions over vast swaths of uninhabited land, lives by and for his freedom to move, and is willing to undertake labors for which no ordinary man is suited. Mad Max, in fact, perfectly personifies the gaucho spirit.

Good-bye, Gaucho?

On an otherwise listless wall near the San Antonio de Areco plaza, hand-painted tiles let visitors know that the town’s master rope-braider once made rope “like Bach made music, Goya painted, or Dante wrote verse.” At the nearby fiesta, merchants sell the essentials of the modern gaucho panoply: handmade bridles, intricately carved wooden stirrups, and an overwhelming selection of fancy mate gourds for enjoying the requisite drink. But are these souvenirs all that remain of a lost era?

UCSB history professor David Rock is the author of the only comprehensive history of Argentina in English. He, too, visited San Antonio de Areco in 2006, and explained to me recently, “I would make the analogy with cowboy celebrations here and there in the U.S.: a pleasant afternoon to witness fine horses and costumes, but an invented commemoration of the past.”

Today, whether or not true gauchos still exist is up for debate. Gauchos themselves admit that their culture isn’t what it used to be. New methods and technologies have conspired against the gaucho’s anarchic spirit, and many young would-be gauchos have been lured away from the countryside. And even those who might be interested in a return to the old ways would struggle. “You can learn,” the grandson of one of San Antonio de Areco’s first cattle drivers told me in 2006, “but it won’t be the same.”

“We’re all just clowns now,” admitted Lorenzo Moreyra, a 62-year-old domador (colt tamer) who still earns a living in San Antonio de Areco by making ornery colts amenable to the feel of a bridle and saddle. “We put on our gaucho clothes,” he said, “but I wear this stuff because my wife likes it.”

Juan Mamani, whose father was the first boot maker in San Antonio de Areco, sells boots and alpargatas. He explained that although one can learn to be a gaucho, fewer and fewer young people are attracted to the hard country life: “Here in our town, there are 10-year-old kids with cholesterol problems!” Other gaucho spectators provided a litany of reasons as to why their ranks are decreasing, the most frequent culprit being technology, particularly video games. “The cyber cafe has become king,” said one old domador.

But economic realities of 21st century agriculture are killing the gaucho too. One man with a craggy face and longhorn mustache explained, “Ranches are getting smaller and smaller. There used to be estancias with thousands of hectares.” But that’s not all. “Soy cultivation, too,” he added. “Landowners don’t keep animals anymore. How’s a gaucho supposed to get around the countryside if there are no horses? On foot?” And according to the nameless narrator of Don Segundo Sombra, “a gaucho on foot is fit for nothing but the manure pile.”

Though, as one 74-year-old man told me, “Progress in nice.” In 1950, his uncles drove 1,000 head of cattle more than 250 miles. “It took 30 days,” said the man, whose blue-green eyes were full of light. “Now, you load them in trucks and you’re there in five hours. But not everybody can do that-only those with big pockets, as we say around here.”

Seeing that this man was decked out in traditional gaucho dress and about the right age to have really ridden the pampa, I thought that maybe I had found an authentic gaucho. I was wrong. “I’ve lived in the country,” he said with satisfaction, “but no, I’m not a gaucho.”

How the Grill Connects All Gauchos

So what exactly is a gaucho in today’s world?

“First and foremost,” agreed gauchos and pseudo-gauchos alike at the 67th annual Fiesta de la Tradici³n, who were all eager to set the record straight, “a gaucho has to know how to slaughter a lamb and barbecue it.” And then they repeated in unison to remove all doubt: “Barbecue-not so much cowboying.”

Even the domador who had complained about the Internet cafe, who had previously been reluctant to let loose more than a few words at a time, was emphatic on this score. “You see all these guys out here who call themselves gauchos?” he asked, waving his arm to show exactly what he thought of those halfway horsemen. “When it comes time to barbecue, they don’t know what to do.”

No one can doubt that there is less and less space for the gaucho to roam in today’s fenced-in world. Such traditional arts as rope braiding, colt taming, and payada guitar dueling are slowly disappearing from the South American pampas, and most 21st-century college graduates won’t find those skills very marketable. But barbecue, now there’s a gaucho pastime that is no less relevant for UCSB Gauchos living 10 to a Del Playa Drive house than it was for the first solitary riders wandering the Argentine plains for days at a time without seeing another soul.

UCSB student Takeo Kishi, who spent last year studying in Argentina and Chile, agrees. He does a lot of barbecuing, and he compares the lawless and animalistic air of Isla Vista to that of the harsh pampa environment where the gaucho thrived. He is also quick to emphasize that while barbecue smells fill the summertime air in Isla Vista, just as they do in South America, UCSB students have a long way to go before they achieve the sublime grilling style prevalent in Argentina. Most I.V. barbecues feature hamburgers quickly cooked on gas-powered grills, and Kishi believes both the food and the method would be the shame of any Argentine asado, where enormous cuts or entire sides of beef seasoned only with salt are cooked for hours over smoking coals.

“But there are a few students who know what they’re doing,” said Kishi, who appreciates both tradition and ingenuity in grilling. “And I count myself among those people. We use charcoal at my house, but we like to grill anything. Meat, vegetables, bananas with chocolate wrapped in tinfoil : “

It seems that when students like Kishi take a study break to enjoy a good barbecue, it is then that UCSB most properly celebrates the gaucho-gauchos like those who amazed scientists and inspired great writers many years ago, and gauchos like those in San Antonio de Areco today who refuse to let tradition die.