Vampires are all the rage at the movies-again. The enduring allure of vampiric mythology is no surprise, given its liberal mix of death, desire, sex, violence, and things going bump and slack in the night. The undying saga’s fangs are bared in all manner of ways, including cheesy romps playing up the “I vant to suck your blodd” kitsch factor. But the tale can also fall into artistic hands, whether in F.W. Murnau’s 1922 classic Nosferatu, Werner Herzog’s remake, or, to a strong degree, the fascinating and weirdly meditative new Swedish model, Let the Right One In.

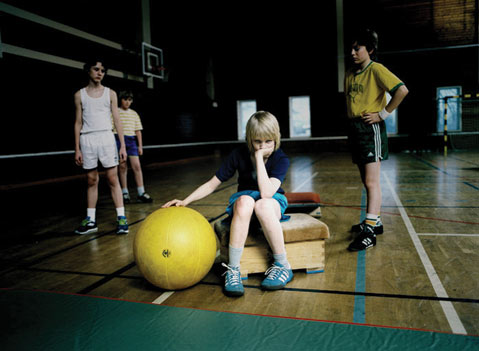

This time, director Tomas Alfredson delivers a sordid tale in cool, slow terms, effectively drawing our attentions and affections in before carefully meting the necessary shock tactics and blood-letting moments. At the center of the story is the androgynous and “young” vampire, Eli (Lina Leandersson), who cites her age as “12 : more or less.” Eli has moved into a town near Stockholm, and strikes up a friendship that turns into young love with Oskar (K¥re Hedebrant).

Deftly weaving the vampire-on-the-block narrative with teen romance and revenge, the film proceeds on a steady, stealthy path as the body count mounts and the plot thickens. We become oddly empathetic with Eli despite the fact that she often has blood (i.e. food) around her mouth. As she tells her young friend/lover who desires revenge against his bullying oppressors, “You would like to kill because you want to. I kill because I have to.” Point taken. Humor creeps in at times as well, such as the memorable and deliciously wicked shot-filmed through a window-of a new vampire victim being mauled by a passel of house cats.

Plot line aside, though, one of the film’s real distinguishing marks is its atmospheric power. Much credit has to go to cinematographer Hoyte Van Hoytema’s ingenious and subtle visual scheming. Cryptic compositions keep us on edge and seduced, while hyper-close-ups lend an intimacy both creepy and tender. It’s as if the lingering influence of Ingmar Bergman hovers over a project which takes an artful bite out of the genre.