El Bosque Road in Montecito is a narrow lane winding past old homes hidden behind thick foliage and shaded by oaks. Follow its curves and you’ll arrive at an old estate that’s changed very little since a community of religious sisters began living there 65 years ago. Visitors might not recognize it immediately as a spiritual setting, but pass an hour amid its quiet, reflective beauty and even the most secular among you will find breathing a little easier, a little freer.

For half a century, seven of these acres have been home to a small but quietly famous retreat center called La Casa de Maria. Built in 1955 by a Catholic order of nuns, it eventually evolved into an internationally recognized sanctuary for healing human spirits and supporting innovative thinkers. Santa Barbara has benefited greatly since the Fielding Graduate Institute, Pacifica Graduate Institute, and the Santa Barbara Waldorf School all started here. In the last 40 years, La Casa de Maria has fostered influential movements. A United Nations conference on the environment was conceived at a retreat moderated by Tom Van Sant, whose work with satellite images in the film An Inconvenient Truth revealed, for the first time, that the Earth was dying.

But in recent years, despite its continuing popularity, La Casa de Maria faced disaster, becoming an object lesson in what could go wrong when a nonprofit loses sight of its purpose. What follows is a brief history of the center, the events that nearly led to its destruction, and how it was ultimately saved.

Leaving Eden

The story begins and ends with the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary (IHM), a Spanish order of teaching nuns founded 160 years ago. In 1870, a small group of the women crossed the Atlantic, settling in California and eventually establishing their Motherhouse in Hollywood. The sisters flourished as teachers and caregivers, building a high school, college, and several hospitals. In the 1940s, the order bought the 27-acre Montecito estate for the relatively low price of $35,000 to accommodate its burgeoning novitiate of young women eager to enter the religious life.

On Easter Monday, the novice mistress Sister Regina arrived to oversee the work of converting the elegant estate into a functioning training ground for future nuns. By Christmastime, 90 postulants and novices were settling in, learning the disciplined spiritual life of the Sisters of the IHM. Aside from a few designated moments during the day, silence reigned over the beautiful ground.

Though there were few visitors from outside the order, by the 1950s, several wealthy married couples began to come to the El Bosque novitiate looking for a quiet place to renew their relationships. Soon, a few, including the popular actress Loretta Young and her husband, asked the order to build a retreat house on the property. Sister Regina, now the Mother General and already an experienced builder, began traipsing about the brush looking for an ideal location. She settled on seven acres where the order constructed a chapel and dormitories.

The Sisters of the IHM might have built their reputation for excellence as teachers and nurses, but they were no fools when it came to business. Like all the other IHM institutions, the new retreat center was immediately deeded to its own nonprofit organization. According to Stephanie Glatt, the former Sister Mary Stephano and now La Casa’s executive director, this shielded each institution from liability for the others. Initially only IHM sisters served on the boards, but later, secular professionals with particular expertise were invited to join.

To the secular world, the order of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, with its 400 members living in 60 convents throughout the west, seemed a bastion of peace, good works, and tranquility. But at the Motherhouse in the late 1960s, Sister Humiliata, the new Mother General, knew differently. The world was changing and so were the hearts and minds of her sisters. By 1965, the new pope, John XXIII, called together the historic council Vatican II, which set about bringing the church into the 20th century. Among the many revolutionary changes it initiated in the ancient rituals of the church, it encouraged sisters to modernize their lifestyles.

Chaffing against the rigidity of their communal life, including an unyielding prayer schedule and medieval (not to mention hot) habits, Vatican II appealed deeply to the California IHM sisters. It opened a window bringing winds of change into their constricted world.

Not everyone found the change so refreshing. The Los Angeles Catholic Diocese was then run by the conservative Cardinal James Francis McIntyre. He hated Vatican II so intensely that he even fainted during one of its sessions. Among the many thorns in his side during this time of historic change were the sisters of the IHM. Though McIntyre could be extremely intimidating, the sisters were determined to press on with change.

In 1967, they elected 40 delegates to a special General Chapter meeting at La Casa de Maria for six weeks. The Chapter Decrees that emerged were comparatively radical; sisters would be free, among other things, to choose their field of endeavor, to wear secular clothes, and to pray on their own timetable. The majority supported these changes, and the following year, the order formally approved them.

Predictably, McIntyre could not stomach such independent mindedness from nuns under his jurisdiction and ordered every last IHM sister teaching in the Los Angeles Diocesan schools to be fired. This signaled that the days of the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary as a Canonical of the Catholic Church were now numbered. It was a desperate time. Sister Humiliata flew to Rome for support. Vatican emissaries flew to L.A. seeking reconciliation between the women and the cardinal. In the end, Rome backed McIntyre. In 1969, all IHM sisters received letters from the Vatican instructing them to return to their former code or seek dispensation from their vows. Sadly and reluctantly, about 300 sisters chose to leave the order. These women immediately began planning a lay ecumenical community based on their new Chapter Decrees, a community that would include men.

The 68 sisters who decided to accept the Vatican’s demand were allowed to keep the Sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary as their name. They also received a cash settlement from the women in the breakaway group, which allowed them to maintain a smaller Motherhouse in L.A. where a few surviving nuns remain today. The school, college, and Montecito property now belonged to the 300 ex-nuns who called their new group the Immaculate Heart Community (IHC).

Leap of Faith

Needless to say, it was a jolting change and at first the IHC struggled to understand how they would run their new community. Some of these women had never written a check in their lives. Fortunately, many had gained real business skills running the large order. Carol Carrig, the diminutive former Sister Mary Carol, who was getting an advanced degree at UCSB at the time, was tapped to run La Casa de Maria.

“We were changing, the world was changing, the church was changing,” recalled Carrig. “All of a sudden we had this retreat center. What were we going to do with it?”

A La Casa advisory board was convened and secular Santa Barbarans were asked to serve, including Don George, a well-known Catholic businessman, and its first non-Catholic, the late congressmember Walter Capps, who was then a new professor of religious studies at UCSB. Instead of panicking when McIntyre announced that La Casa was no longer a Catholic institution, the secular boardmembers were unfazed. “What an opportunity,” Capps reportedly said. “Now we can open up to all these other faiths, none of which have retreat centers.”

But what kinds of retreats were suitable? After all, it was the 1970s. At first the board was open to everything from Primal Scream sessions to Christian Dialogues. The Primal Scream groups mostly succeeded in alarming the El Bosque neighbors, but slowly the new community began to find its niche.

In 1971, however, a potentially devastating fire destroyed the center’s main meeting room and the IHC was forced to take stock of the whole operation at El Bosque. They had recently turned the old novitiate building into the Center for Spiritual Renewal for individual retreats, and these additional responsibilities, as well as the cost of maintaining the seven-acre La Casa property, led them to make a decision with sweeping ramifications for the future. The IHC relinquished the running of La Casa de Maria and all its liabilities to its board.

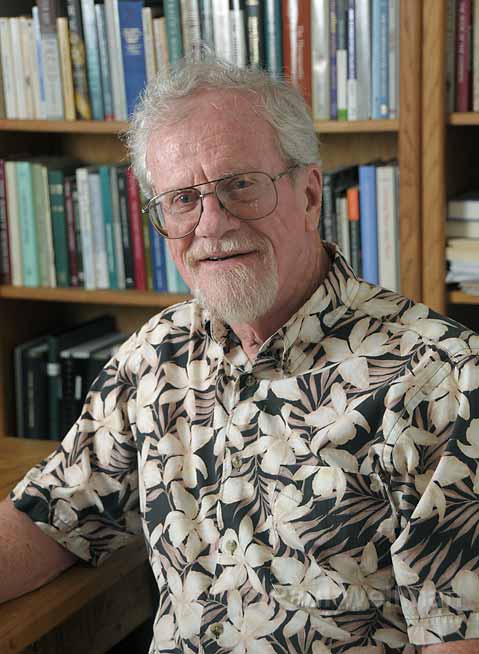

When George became the executive director in 1972, La Casa was running on fumes. But he had an idea to expand weekend retreats into weeklong gatherings. He and his five-member office staff began working the phones and soon booked its first seven-day retreat, a Colorado group called the Order of the Cross, which brought in more money than a month of weekends. Then Westmont College booked its new faculty retreat session there. “The trick was to help [these institutions] understand the gift they would get from coming to a spiritual center, that it stood for more than just making a buck,” George said. “The more people started coming, the more folks began talking about this special place in Montecito.” It was not uncommon to see tough-minded participants hugging one another after intense meetings.

“I saw this happening again and again,” he said. “La Casa has this ability to hold a problem like a hurting child.”

At the same time, George launched the Christian Dialogues series where people told their own personal stories of faith. It was enormously popular and helped form a foundation for Santa Barbara’s extended community. Alliances were forged there, as environmental activist Hal Conklin, who later became mayor of Santa Barbara, can attest.

“[It was] developed to begin a dialogue between traditional Catholics and non-Catholics, but once people started talking, their religious backgrounds became irrelevant,” Conklin said. So affirming did he find these weekends that he volunteered to help run them. By the early 1980s, Conklin knew so many people from Christian Dialogues that “I’m sure it stunned some the first time I walked into City Hall and threw my arms around 16 people and visa-versa.”

Eventually the broader Catholic community began to trickle back, the way smoothed by McIntyre’s death. Most significant was a retreat given by the progressive bishop from Detroit Tom Gumbleton, who celebrated a groundbreaking American bishops’ pastoral letter on peace. This started La Casa’s tradition of hosting peace events, the most famous of which was the 1985 Soviet and American Religious Women’s Conference. Gene Knudson Hoffman, the Santa Barbara Quaker who originated the “Compassionate Listening” technique and the U.S./U.S.S.R. Reconciliation Project, used her diplomatic connections to bring four Soviet women, including a nun, to La Casa for five days of dialogue with four American religious women. A peace garden planted by the women marks this rare Cold War success when human beings were able to transcend their national enmity to find common ground.

By 1990, La Casa was booked a year and a half out. Its 16-member board was half IHC members and half Santa Barbara community members, including Conklin, the late Father Virgil Cordano, Steve Jacobsen of Goleta Presbyterian Church, and retired Episcopal priest David Jones. Everyone agreed the center was ready to expand to a second campus and they started looking around. This is where they took their first misstep.

Fall from Grace

In 1997, a 34-acre former Jesuit Novitiate on Ladera Lane-part of a large real estate transaction undertaken by the developer, entrepreneurial team Chuck Blitz and Roger Himovitz-presented itself. The site’s expansive views and open hillsides seemed perfect for retreat work. Originally listed at $16 million, La Casa got it for five.

From the outset, it was a chancy operation. Though La Casa would be burdened with a $4.8 million mortgage and double the operation costs, in the heady days of the dot-com bubble, it seemed to make sense. They would just have to keep the Ladera site booked. But there were problems from the beginning: the county took a year to issue a conditional-use permit; single guests could stay, but large, group bookings, which would bring the big money, were on hold; more staff and refurbishing would be needed. George, who was 65 and eying retirement, fundraised intensely, but La Casa, which had never needed large infusions of cash, had no established donor base.

Ladera’s mortgage was refinanced twice between 1998 and 2000, and a third loan, for $5.2 million, was granted by the Ruth Mott Foundation. In these years, La Casa’s El Bosque site paid Ladera’s outstanding bills. Legally, they were one organization.

By January 2001, Ladera’s revenue nearly covered operations; things were looking up. Then came September 11th, traumatizing the nation. Groups cancelled events en mass. Adding to the confusion, the five years George had agreed to stay on were now up. It was time to hire a new director.

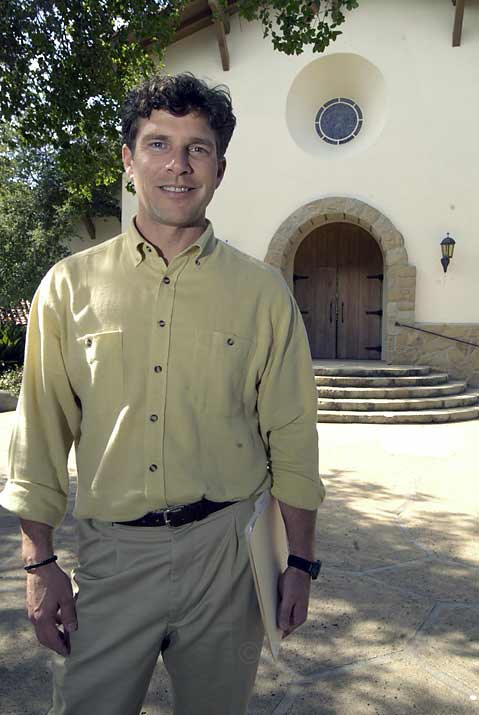

Enter Jim Villanueva, who seemed the perfect choice. He was an independently wealthy forty-something private equity investor from Los Angeles, the grandson of Mexican immigrants and son of L.A. Rams star kicker Danny Villanueva. He and his wife, Sherry, a marketing and idea consultant for Target Corporation, had left L.A. culture behind in 1999 for what they hoped would be a more grounded life in Montecito. When he accompanied his eldest daughter to a youth retreat at La Casa, Villanueva was inspired to volunteer for the Advisory Committee, which brought him to the attention of the search committee. Their primary candidate for executive director had just withdrawn at the 11th hour and Villanueva, with his youthful confidence and Stanford MBA, looked like someone who could finally dig out Ladera from its mortgage.

Looking over La Casa’s financials, Villanueva concluded the organization was turning the corner and accepted the position in fall 2002 at $124,615 a year, high by Santa Barbara nonprofit standards (at the same time, the Fund for Santa Barbara’s executive director was making $52,500). It was particularly high by La Casa standards. George’s salary had been half that, though it did include a three-bedroom house onsite. All other staff earned, according to La Casa’s Glatt, $10-$22 an hour.

The honeymoon for Villanueva didn’t last past lunch on his first day because it was around then when he discovered La Casa was in default on its mortgage and couldn’t make payroll. He broke the news to the board.

How events evolved, or devolved, from there depends who’s telling the story. In many ways, La Casa became the victim of a culture clash. Villanueva, trained in the world of commerce, was someone for whom the ethics of fiduciary principle made complicated questions clear-cut. The IHC and La Casa staff, on the other hand, lived a grassroots philosophy founded on the cycle of retreat work, the preparing for and taking care of guests. Their sense of the future came from their faith and their relationships with one another. That the center would survive was taken on trust, even in the face of very bad numbers.

No one argues Ladera’s $45,000 monthly mortgage was a problem or that fundraising post-9/11 was impossible. But it was how the board responded under Villanueva’s leadership that was, and is, a source of the problem and of the great grief experienced by many La Casa loyalists.

At first, Villanueva acted swiftly and well, renegotiating Ladera’s mortgage. And when the Ruth Mott Foundation threatened to begin foreclosure proceedings if La Casa didn’t pay up or find a buyer by October, Villanueva refinanced. However, when he announced he was adding a new position to the already struggling payroll, it was surprising that he hired his old Stanford classmate Rick Beckett as an assistant at an eventual yearly salary of $120,796. This might have been de rigueur in the business world, but it surprised the staff, even though it was approved by the board. Next, he rescinded the longstanding policy of allowing associate directors to sit in on board meetings. This also alienated some staff members, who considered the fate of La Casa to be a shared responsibility. But such openness in a financial crisis seemed, to Villanueva, irresponsible.

Around this time, for personal reasons, two benefactors withdrew big gifts. Meanwhile, everyone has agreed that operating expenses, including salaries, gobbled up whatever funds were raised. Villanueva said that on his watch he kept La Casa from bankruptcy on six separate occasions.

In spring 2003, he initiated a restructuring, cutting in-house programs and firing 14 staff members. Retired Episcopal priest Jones acknowledged the layoffs were poorly executed. “It had been a family,” he said. “And it’s not always a good idea to treat a family legally.”

Then the board approved a desperate move, taking out a million-dollar loan against its El Bosque property. Some claim Ladera was breaking even by 2004; whatever the case, the mortgage was still a ball and chain. And now there was another loan to pay. Loose talk about selling Ladera began to coalesce into a plan.

Finding the Promised Land

Many wonder how La Casa’s board, which loved its El Bosque home, could reach the point where it would consider selling it too. But the answer lies in the progressive souring of the relationship between the board under Villanueva and the IHC. As early as 2003, chances for a happy ending between them were finished. “We were listening from a nonprofit standpoint and they were talking from a business standpoint,” said one staff member.

The board and the IHC had a Joint Use Agreement for the center’s use of sections of the property belonging to the community that La Casa needed for spillover. In exchange, La Casa paid a fee and maintained them. It had been a five-year contract that rolled over annually. But in 2004, the IHC asked for changes, including a shorter renewal period. Negotiations stalled. Enflamed passions framed every decision. Finally, Villanueva said, La Casa didn’t get what it needed to continue operating there; the period of renewal was so short, long-term investments weren’t possible. So the unthinkable finally happened: The property was appraised in preparation for sale.

The appraisal value of La Casa de Maria and its seven acres was $10 million if it remained a retreat center and $6 million for the raw land.

“We were going to do everything in our power to make sure that spiritual retreats continued on that property, preferably under the IHC,” said Ken Saxon, a community volunteer who joined the board in 2003.

The very first conditional-use permit negotiated for La Casa in the early ’70s gives a right of first refusal to either the retreat center or the IHC in the event one or the other puts their portion of the estate up for sale. So in spring 2004, La Casa’s board offered the El Bosque center and its seven acres to the IHC for $6 million. The IHC rejected it. It took a year and a half and several time extensions on the part of La Casa’s board for the parties finally to agree on a price: $4.5 million. Each of the remaining 160 IHC members, many in retirement homes, gave $1,000 toward the down payment. Escrow closed in April 2006.

Meanwhile, La Casa de Maria (the nonprofit, not the El Bosque property) prepared to change its name and mission and parsed the fine points of a sale of Ladera to Pacifica Graduate Institute. The new name was the Eleos Foundation-Eleos being Greek for compassion joined with a desire to help. Ladera went for $12 million plus permanent office space. After debts were paid, Eleos walked away with $7 million free and clear, a quarter of a million dollars of which has been granted to nongovernmental organizations in Kenya, Zambia, and India.

Not all of this sits well with long-time friends of La Casa, including Conklin. “What caused the real grief was to mortgage El Bosque and then take the money and put it into something else. That was morally wrong,” Conklin said.

But Villanueva and other Eleos boardmembers, including the former IHM sister Francis Snyder, believe that in the 40 years La Casa operated separately-its investments in those seven acres, the buildings built, the funds raised-entitled the nonprofit to some return.

“We bent over backward to try to be fair to both sides,” said Villanueva. “I was a director of an independent nonprofit, I had creditors and a mission. We could share the value of that property, but I [couldn’t] just give away the assets.”

It’s been two years since escrow closed on the IHC’s repurchase of their retreat center. Since then, they’ve paid their mortgage and brought back programs. Last year, some Israeli and Palestinian women brought their reconciliation movement to La Casa and the eighth annual Barrett Conference on the Ministry of Women took place. Driving up El Bosque after dark, the conference room was aglow as women sat at round tables, votives flickering at their places, listening to a speaker. Many of these women were juggling jobs, kids, and relationships. By Sunday, most of them would be ready to resume their high-wire acts. They were getting a moment to breathe. La Casa de Maria had survived another struggle to do what Sister Regina intended that day she slogged through poison oak looking for a spot to build its chapel-restoring the weary and giving them hope.