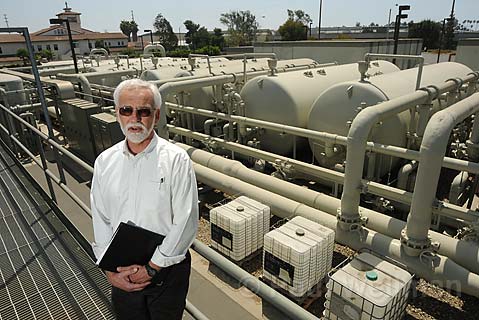

By a narrow majority, the Santa Barbara City Council voted to spend $122,000 on studying what it would take to bring the city’s 18-year-old desalination plant out of moth-balls and up and operating again in case of emergencies.

Water planners argued the study would provide solid information about how much it would cost to make the desal plant – on which City Hall spent $34 million in 1991 – operational, whether new technology might reduce the energy demand, and what permits might be required. They also argued such information might prove useful as Santa Barbara prepares to revamp its general plan. Councilmember Das Williams worried that a new water supply – the original desal plant was designed to produce 7,500 acre-feet of water a year, more than half the city’s total water demand – would prove growth inducing. He argued City Hall should spend its money studying how much more water could be saved through conservation, the long-term effects of climate change, and how City Hall could further its water recycling efforts.

Mayor Marty Blum argued that the cost of desalinated water was 25 times the price of its existing water and hence too expensive to fuel further growth. She said it would be “irresponsible” for the city not to find out what’s involved in re-activating the desal plant. And Councilmember Dale Francisco said such an emergency water supply could prove essential if the tunnels connecting city water customers with Santa Barbara’s two main reservoirs were to collapse in an earthquake. Without such a fall back plan, Francisco predicted, “There would be a lot of finger pointing and they would be pointing, justifiably, at us.”