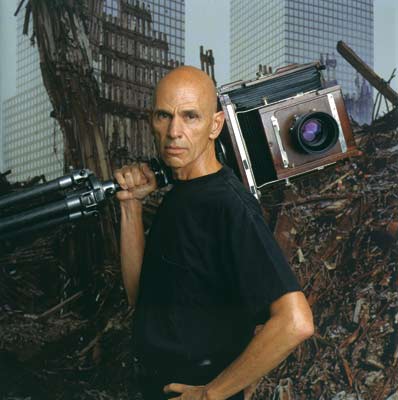

When the events of September 11, 2001, engulfed New York City, native New Yorker and photographer Joel Meyerowitz was on Cape Cod. As he watched the tragedy unfold, he was hit with an overwhelming desire to be of service. Previously known for his contemplative studies of people and place in poetic monographs such as Cape Light and Tuscany, Meyerowitz hit the streets of his city to document what he saw. As the only photographer allowed into Ground Zero, his book Aftermath is the only visual archive of the 9/11 relief effort.

What drove your desire to make this photographic archive? I am a native New Yorker. I was born in the city and lived not far from where this event took place, but I was in Cape Cod at that moment. My first impulse was to go back to my home base to help in some way, but I wasn’t allowed to go back to the city because they had closed access. When I did return, five days later, I still found myself with this continuing need to be useful.

Was there a defining moment that gave rise to the project? I took myself down to the site on the day I returned to get a feeling for it, and there I had this strange interaction with a policewoman. I was standing in the crowd and looking through my camera, and this cop struck me on my shoulder and threatened me. I was told that I couldn’t take pictures because this was a crime scene. We were standing on a public sidewalk in New York City, so I told her, “I am a citizen of this city and I can actually do this,” and she started to fight me. Then she threatened to take my camera away. They simply couldn’t do this to us, because it would take away history. I suddenly found myself politicized and realized this was what I could do to help.

Did you set yourself guidelines for working on-site, or were you simply responding to what evolved? It was hard to completely preconceive what I had to do, but what I did understand was that there was a model for this. During the Depression, and what was known as the Dust Bowl Era, the government formed a team called the Farm Security Administration, and photographers such as Walker Evans, Russell Lee, Dorethea Lange, and many others-who were not journalists, but serious photographers-went out with a shopping list of things to capture that would describe the Depression in a larger view. I, too, used that method for Ground Zero. I wrote a shopping list and used that as a principle so as to photograph all the aspects of the site: what it looked like, how it was being cleaned up, who the participants were, what methods they were using, and what support services were in place. It was an intense zone-only four square blocks-but thousands of people and a vast assortment of divisions were in action, and I wanted to describe the entirety so that, in the future, people could see the anthropology of the whole site.

What defined your choice of equipment? I worked with three different instruments in this instance. I used a view camera because I felt that it was imperative that the quality of the image be as precise and exquisite and extraordinary as possible, and the images should have the magnitude to make enormous photographs that have a sense of reality. But I also carried a Leica, which is 35mm, and a Mamiya, which is medium format, so that I had other instruments that I could work with quickly and spontaneously if I needed to. These offered me the capacity to describe the human aspect.

You are bringing a projected presentation of your images to accompany your talk. How does that kind of presentation differ from the personal and meditative experience of being alone with a photograph on the wall of a gallery or in a book? I love the meditative quality of being alone with a work and responding to it in my own tempo, especially with photography, which is this illusion of the real world. But there is no denying the group psychology. And, given the nature of digital presentations today, the quality of images in digital form, you can make a beautiful large-scale image. I have found that audiences have been incredibly moved and very responsive to these reproductions on a screen. The mass appeal of being in front of an audience and sharing one image with 500 people at the same moment is the same sort of experience we get in the theater. I was surprised how much of a community experience it is.

4•1•1

Joel Meyerowitz will speak and give a visual presentation of his work at UCSB’s Campbell Hall on Monday, May 12, at 8 p.m. For tickets or more information, call 893-3535 or visit artsandlectures.ucsb.edu.