Bobby Lesser’s Film Role Puts America on Trial

Wars of Honor and Humility

It was the middle of December and raining hard in Santa Barbara when I met up with actor Robert Lesser to hear his story about the film he made in Japan. Standing in a parking lot with him while he checked the trunk of his car for an umbrella, I got a glimpse of what the life of an actor is really like. There, amid the tennis rackets, beach towels, and, fortunately for us, golf umbrella, were the traces of a lot of time spent commuting from Carpinteria to Los Angeles for auditions, whole years devoted to a craft that requires unimaginable patience and a high tolerance for the pain of rejection. When actors get together for coffee, they tell stories for support-to stay active, to be ready, and to keep hope alive. Talk about work-work past, work present, and most often, work to come-is what keeps the flame of hope in every actor kindled.

I already knew this conversation with Bob Lesser would be special; this was to be the tale of the big one that didn’t get away, a dream like the one just about every actor I have ever met lives by. He had gotten a role in a Japanese war movie, a big-budget production directed by Takashi Koizumi, Akira Kurosawa’s second-unit director for Kagemusha and Ran. The film, called Ashita e no Yuigon, or Best Wishes for Tomorrow, told the story of a war crimes trial that had taken place in Yokohama in 1948. A Japanese lieutenant general, Tasuku Okada, and 19 of his subordinates had been tried by an American military court for their involvement in the beheading of 38 American prisoners of war. The American fliers had bailed out over Honsh¹, where Okada and his men had captured them. The charge brought against these American Air Force fliers was that they had knowingly violated The Hague convention’s 1923 Rules of Aerial Warfare by carpet bombing Japanese civilians, and in some cases they had been convicted and executed in a matter of just hours.

Born in Los Angeles but raised in New York City, Lesser has paid his dues in every conceivable dramatic situation, and has lately shown an aptitude for cerebral (and notoriously difficult) comic roles. Lesser is well known and well liked in the Santa Barbara theater community, and his reputation extends far beyond our town. He started out in movies playing an agent in the legendary independent film David Holzman’s Diary, and he has been in dozens of Hollywood films and network television programs since. From Hester Street to Herman’s Head, from The Goodbye Girl to Godzilla, Lesser is the kind of actor who has been working all his life, yet still yearns for that breakthrough role that will put him at the center of the story. He lives in Carpinteria with his wife, Ann Bardach, who is an award-winning investigative journalist and one of the world’s foremost experts on Cuba. Bardach and Lesser are the kind of couple Santa Barbara thrives on-talented, prolific, and committed to seeing the big picture.

Becoming the Hero

Lesser was cast as the defense counsel, Joseph Featherstone, opposite a famous Japanese actor, Makoto Fujita, as Okada. Lesser’s role would call for him to utter the words of a historical figure, many of which were recorded in the official trial transcript, and to reenact Featherstone’s defense, which rested on a claim that, at the time, was nothing short of amazing. According to the defense, Okada’s judgment was correct: America was guilty of war crimes in its bombing of Japan. Buried in this obscure (to Americans) footnote to the aftermath of World War II was an incredibly powerful historical moment-perhaps the first legal attempt made to bring America to the bar of international justice for the bombardment, including the first official statement in a court of law that the use of nuclear weapons should be considered a war crime. In any language, this would be a major role, and it got even better when Lesser learned that a good friend, Richard Neil, would play Colonel Rapp, the president of the Military Commission and judge for the trial.

One thing about his character, defense counsel Featherstone, Lesser said, was that “there’s no way he doesn’t feel the awfulness of the event that set off this whole thing. He is as aware as anyone of the tragedy involved when the fliers were executed. But that doesn’t stop him from putting up a vigorous defense of Okada and his men for over three months by focusing on American war crimes and violations of the Geneva Convention.” Lesser added: “You can’t help but be moved by the fairness of the thing.” So I asked Lesser, “then Featherstone is the hero, right?” But there seemed to be more than one answer to that question. In Japan, Okada was the hero, but Featherstone was still important. As Lesser got deeper into his explanation, I sensed that Ashita e no Yuigon was not like other films. Something different had gone on here, and the actors’ identification with their characters was at the heart of it. From an enthralling tale of success and respect in a foreign land-as in, “maybe they were confusing me with some important movie person from California”-emerged the contours of unfinished business. At times it seemed as though the director, Koizumi, had convinced his cast that they were free to change the outcome of the trial.

Lesser achieved such a sense of conviction about his character’s expectations that he felt victory in the trial had only just eluded him. He said that to him, Featherstone was a hero but that “being the hero doesn’t always mean having the best role. The prosecutor in this story is very unpleasant and aggressive; a villain, from my point of view.” He was talking about Chief Prosecutor Richard Burnett, the third of a trio of parts played by Americans. The role of the prosecutor was taken by Fred McQueen, an actor who has only recently begun appearing under the name of his father, Steve McQueen. Bearing a striking resemblance to the elder McQueen, who took no part in his upbringing as Fred Spiker, the actor who played the prosecutor is a foil for Lesser straight out of central casting. They disagreed about everything. As close as Lesser was to Richard Neil, he was distant from Fred McQueen, who would be the only other American actor on the shoot. As Lesser said, “As long as we didn’t talk politics with McQueen, we were fine. He is from the other side of the aisle, as they say. He thought that the historical general Okada was a monster, and took every opportunity to say so. Politically, McQueen is somewhere to the right of Attila the Hun.” Thus the plot of this actor’s tale thickens.

Baby’s on Fire

Best Wishes for Tomorrow opened in Japan in March to coincide with and commemorate the anniversary of the fire bombing of Tokyo on March 9-10, 1945. These allied missions, flown by American Air Force B-29 bombers, were among the most devastating acts of destruction in the history of warfare. Stripped of armament so they could hold more incendiary clusters and napalm canisters, the B-29s came in so low that Japanese civilians saw the flames that consumed their homes reflected on the undersides of the bombers’ wings. Survivors of the Tokyo fire raids told some of the most horrific stories of the Second World War. From Elie Wiesel and Primo Levi we have learned about the camps and the holocaust, but how many of us in this country have heard stories like this one:

Until the moment Yoshiko Hashimoto jumped into the river, she had been almost comatose with fear and the pain of the intense heat. The water revived her. She saw a tangle of lumber, partly ablaze, floating past. Seizing this with one hand, with the other she managed to push her baby onto the flimsy raft. : Even in the river, the heat was overpowering. -from Retribution: The Battle for Japan, 1944-45 by Max Hastings (Knopf, 2008)

Reading through the recent literature on these late WWII atrocities, my view of the resolution of that conflict shifted with a sickening thud. The reason all those high school history class debates about the necessity of using atomic weapons to end WWII had never come to anything is because high school American history had mostly overlooked one very simple and significant fact-we had done something worse to Japan already. The Tokyo fire raids and the 60 or more similar missions flown by the Air Force against urban civilian Japan in the final months of the war were actually more deadly than the nuclear bombs that had come to symbolize America’s ultimate level of intimidation.

The architect of this astonishingly cruel plan, which killed hundreds of thousands and rendered millions of Japanese homeless, was General Curtis LeMay. When asked about his achievements after the war, LeMay reportedly said with evident and unrepentant pride, “We scorched and boiled and baked to death more people in Tokyo on that night of 9-10 March than went up in vapor at Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined.” The B-29 fire raids were thus the hyper-violent background against which nuclear force appeared. When compared with carpet bombing, the atom and the hydrogen bombs were understood as merely more efficient, rather than different in their scale of destruction.

The problem with LeMay’s “great success,” which was lauded as such by the American press and government, is that it involved a fundamental shift in the targets, which had initially been military. In retrospect, there is no question the use of large aircraft to incinerate civilians and to drive them from their homes in terror is a powerful gesture. Destroying urban civilian life for symbolic effect dampens morale, and on the scale undertaken by the United States against Japan in 1945, it is likely that it broke the Japanese national will to continue fighting. When the big planes come and burn all the cities down, pretty much everybody loses the will to do anything. The whole time I was researching this subject, a surreal song lyric from my youth kept elbowing its way back into my head. It’s from Brian Eno’s rather creepily titled album Here Come the Warm Jets-side one, track three-and it goes like this: “Baby’s on fire / Better throw her in the water.”

Seeking Justice

Back in Santa Barbara, where the rain continued to fall, Bob Lesser was just getting to the point of his great actor’s story. What had started out as a hymn to Japanese hospitality had gradually gotten more serious. One minute Lesser was saying how great he felt when he came to the set every day and all the actors and extras were given cloths to wipe their shoes, and the next he was regretting some of the decisions he had made as defense counsel Featherstone. Just like a lawyer who had lost a big case, the actor was going back over the trial, imagining a new performance, one with a different result. He said that, if he could do it again, “I would have come at the prosecutor harder. I think Featherstone went too easy on him. If I could do it again, I would get them to scream out from the gallery.” In Lesser’s mind, the outcome of the dramatic re-creation, like the outcome of the trial itself, seemed to have been in doubt the whole time, despite the script or the weight of history.

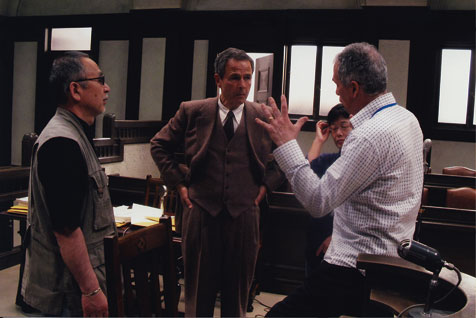

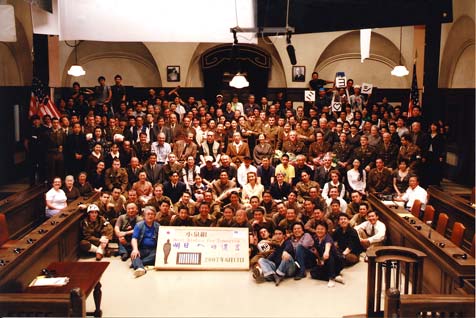

Cameras were not allowed into the acting space. When close-ups were necessary, it was done by changing lenses. Lesser compared it to stage acting in the round and said “the director did not shape these scenes for maximum dramatic impact. He really went for the sense of just how it was. Even some things that are long, boring, and drawn out were done in full, because for a long time it would be boring, but then suddenly it’s not, and that’s what he wanted, those sudden moments when it is not boring. And that’s what he got.” The gallery was always filled with costumed extras; no scenes were shot without the full complement of actors and spectators present for the entire day. Camouflaged by a conservative, Kurosawa-like visual style, Koizumi has made something that is not a conventional film. There is a quality of ritual, and a reaching after history that one doesn’t ordinarily see, even in very painstaking period reconstructions.

Festival Time

By the time Best Wishes for Tomorrow arrived at the 2008 Santa Barbara International Film Festival, more than a month had passed since our talk, and although it was still raining, it had not rained for the entire six weeks. Takashi Koizumi was there, resplendent in hipster black, and accompanied by a translator. Richard Neil was there too, and Fred “Spiker” McQueen, along with Bobby Lesser and Barney Brantingham, who conducted the follow-up question-and-answer session. The theater was absolutely full, and some people were even turned away. What came next was exhilarating, and revealed a crucial detail that Lesser’s story had not been able to supply-just how damned good he was in it. The film’s screenwriter, Roger Pulvers, has written about this performance, commenting:

Lesser, as Featherstone, accessed an enormous fund of empathy for the general and what he was going through. I can think of very few American actors who could have handled this part with more depth and subdued passion.

The performance I saw at the SBIFF screening was a different Bob Lesser than I had seen before, despite having enjoyed several of his expert stage roles in recent years. There was a yearning in his portrayal of Featherstone, a bright light of humane compassion that shone out of every gesture, irradiating the performance with his concern for his client, the general. When Okada’s children came to the trial, Featherstone’s eyes beamed with the pride of a father.

Of all the actors in Best Wishes, even including the wonderful Makoto Fujita, it is Lesser who makes the most out of the physical aspects of the cultural clash. He bows with the grace of a Japanese native and the enthusiasm of a Brooklyn Dodger fan. His account of this aspect of his performance is shot through with a characteristically self-deprecating humor, as he explained: “I do a lot of bowing in the film, which is something that came naturally to me, being an actor. Usually you have to wait until the end of the play, but over there you can throw in a good bow just about any time and it’s okay. In Japan, you bow before you do the play. You can’t bow too much, but you should probably be careful not to bow too low, which is my tendency. They gave me a samurai sword to take home, which was not easy to explain to airport security.”

Following the screening in Santa Barbara, the three American actors quickly slipped back into their roles from the shoot. McQueen started talking trash about Okada, and Lesser and Neil looked on in bemusement, then rose to the bait. The dynamic set in motion by the reenactment of the trial continued, but now I savored the lingering afterimages of the film-a rowdy scene of Okada and his men bathing, a delicate farewell between Featherstone and Okada, the desolation of the sunrise over the execution. Some of the words I had heard came back as well, like when Featherstone had spoken into the record that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were war crimes according to international law. Most of all, I remembered General Okada’s improbably sublime and deeply Buddhist final pronouncement, a little hymn of praise for the procedure that would end by sentencing him to death. In his official final statement on behalf of himself and his 19 men, Okada said, “We have been coming to this court daily with a feeling of satisfaction and with the added feeling of gratitude to this court. [These feelings] are as clear as the deep blue sky without a single cloud in it.”

Clear as blue sky to this Buddhist Japanese general more than 60 years ago, it’s hard not to feel that the core principles of our justice system, including the right to counsel and a fair trial for enemy combatants, have been lost in the fog of war. For Bobby Lesser, Best Wishes for Tomorrow was much more than a soapbox for revisionist history; it was a chance to step into a role with symbolic weight beyond the limits of any simple plot. In creating Joseph Featherstone, and endowing him with emotional life, Lesser took on an identity of lasting historical significance. From firm ground in research, and through the painstaking reenactment of an arduous procedure, these actors, Americans and Japanese alike, have established an elemental dramatic connection to the greatest of all of America’s contributions to world culture-the idea of justice as the result of a fair trial.

Best Wishes for Tomorrow may not be a film for the war movie crowd-there’s barely any violence, for one thing. But in time it should claim the interest of another, potentially much larger and more important audience, an audience of people everywhere who care about these wars of honor and humility, the battles that are fought in courtrooms-and occasionally on film sets-in countries where such values still prevail. As for the inspiring actor’s tale, the one that kindles hope, it’s the same as it ever was: You’re going out there an actor, but you are coming back a hero.