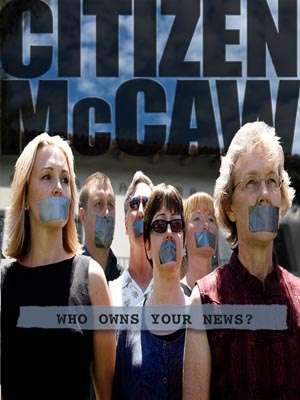

For a while, they were calling it The Last Reporter. “And that was a shorter version of the longer, real title,” explained Sam Tyler, the documentary-maker who gave birth to this definitive News-Press documentary, which debuts at the Arlington on March 7. “The longer version was Will the Last Reporter Leaving the Building Please Turn Out the Lights. For a while we also wanted to call it Trouble in Paradise. I don’t even remember who came to us with the title,” he said. Given the circumstances, including newspaper owner Wendy McCaw’s increasing isolation amid public tumult, mass firings, departures, and union disputes, the phrase-with obvious echoes of Orson Welles’s fictional study in lonely hubris-seemed to suggest itself. “It just stuck,” explained Tyler.

What’s telling about the selection, however, is the effortless collaborative nature that marks the whole production. Not that it’s been easy work for the four people most responsible for producing Citizen McCaw in a small studio above a Starbucks within eavesdropping distance of De la Guerra Plaza, but it did seem to come together well after Tyler made the initial calls. Boston-born, though a Montecitan since the late 1980s-he claims McCaw’s boyfriend and NP copublisher Arthur von Wiesenberger as a “former golf buddy”-Tyler long made docs for PBS-affiliate WGBH based on successful business-oriented books like Tom Peter’s In Search of Excellence. He had just finished a film based on Jim Collins’s Good to Great when he returned to town in the summer of 2006 during the newsroom walkout. “I sensed a major story was unfolding right in my backyard,” he explained.

For those living in Xanadu, the NP meltdown captured in Citizen McCaw unfolded very publicly, but the in-house unrest began immediately after McCaw bought the newspaper in 2000. The noisiest period began with McCaw’s anger at her reporters for publishing actor Rob Lowe’s address and reverberated nationally when former editor Jerry Roberts led a newsroom exodus. He was later sued by McCaw, who then used the front page of her paper to suggest that Roberts had downloaded child porn. This-teamed with more firings, federal hearings, and countless McCaw-launched lawsuits-erupted while Citizen McCaw was being filmed.

Also on the team are playwright and Marjorie Luke Theatre renovation director Rod Lathim; Carpinteria screenwriter (Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Shrek the Third) Peter Seaman; cinematographer Chuck Minsky (Pretty Woman, You, Me, and Dupree); and Brent Sumner, a recent Brooks Institute grad. “I got a call from Sam and I could tell his blood was up,” laughed Seaman. “How I got involved? I’m not sure how it happened.”

Sumner agreed. “Look, I had Rod Lathim, who everybody in Santa Barbara knows, who can open any door; Chuck Minsky : [so] if nothing else, the film would look good; Pete Seaman speaks for himself. I’m a linear guy; so far, I’ve just made films based on books. Here there was no book, no clear story.” Sumner’s energy and talents became immediately obvious-at times when the others were unavailable, Sumner took it upon himself to cover events that later proved crucial.

Certain paradoxes were involved. Though Tyler once produced puff pieces about great management, he was suddenly investigating a business in falling-apart mode. Seaman, a studio screenwriter, was used to turning in work that he might see months later onscreen. “Suddenly I was the one who was deciding what would be up there. It was kind of nice,” he said. In fact, Seaman changed the film’s structure radically from a straightforward tragic narrative to a thematic exposition. “Pete saw it as the triumph of the little guy,” said Tyler.

Lathim presents the most dramatic contradiction. A fourth-generation Santa Barbaran known for championing the rights of disabled people, his reputation rests on inclusiveness-the idea of civil society. Now he helms a film with potential to divide the town. “In a way, I had to do this,” Lathim said. “I was going through files recently and I found a copy of the News-Press with a picture of me at one year old. My grandpa knew Thomas Storke. This paper was a part of my life growing up.” The public reaction to his involvement nonetheless surprised him. “People have been calling up and asking me if I’ve gone nuts,” he said. “But the last time I looked, this was still America, and I think it’s important that we do this. The level of public trepidation about this is obvious. This is wrong.”

Fear is an important theme. The filmmakers’ worries were confirmed early when McCaw’s attorney Barry A. Cappello attempted to subpoena footage they shot at a demonstration. Though a court denied the motion, Tyler and crew are still scared of future litigation. They’re hyperconcerned about balancing their reporting to avoid charges of bias, or worse, libel.

Though the filmmakers assert that McCaw and associates had ample opportunities to give their side of the story, Cappello claims that’s false. Due to ongoing legal proceedings, he said it was inappropriate for NP management to comment on camera, though they furnished the filmmakers a letter outlining their positions. The newspaper’s position is clearly stated in the film, say the filmmakers, which should satisfy any legal responsibilities they have. Cappello, however, claims the filmmakers have an obligation to fact-check the film with him, and that failure to do so “would imply malice,” as he put it, and open the filmmakers to libel charges.

The story itself isn’t just about fear, though. The film, according to those who’ve seen rough cuts, is memorable for the pains felt by Santa Barbarans. Jerry Roberts’s emotion is palpable and touching. Other passionate witnesses include Mayor Marty Blum and this paper’s Angry Poodle, Nick Welsh. “There were no bad interviews,” said Sumner. Surprise guests include some of the biggest names in American newspapering, such as Ben Bradlee of the Washington Post. Two famed reporters who live here and occupy opposite ends of the ideological spectrum also weighed in. “You could have made a whole movie out of either Lou Cannon or Sander Vanocur’s interviews,” claimed Minsky.

Probably the hardest job was cutting good stuff. The documentarians shot close to 80 hours of film and brought down the material to 85 minutes. “We had to cut a lot of darlings,” said Minsky. “For those who haven’t followed the story, we’ve got two years in 80 minutes,” promised Tyler.

Even news junkies will likely learn something. Tyler himself didn’t expect the amount of public apprehension he found stalking our streets, the unwillingness of people to come on camera. All four told me they firmly hoped this film might provoke a less inhibited public conversation-one that included Wendy McCaw. Separately, though, Minsky, Seaman, and Lathim told me they came away with a new respect for what a newsroom reporter does, never mind what he or she stands for metaphorically.

“You know Ben Bradlee said it best in the interview,” said Seaman. “He talked about following the news wherever it leads you, that the publisher has no friends, and that there are no sacred cows. I now have a new respect for the people who do that work.”

4•1•1

Citizen McCaw debuts on Friday, March 7, at 7:30 p.m., at the Arlington Theatre. The producers will speak afterward. Call 963-4408 or see citizenmccaw.com.