Tradition and Transition: The California Missions

Etchings by Henry Chapman Ford and Leonardo Nu±ez. At Channing Peake Gallery. Shows through February 15.

Like Tibetan sand paintings-earthen works of art created in response to religious imperatives and designed to be ritually blown away-the California missions had a planned obsolescence. They were meant to stand as inspirations to so-called heathens only as long as it took the Spanish padres to convert them. They were then supposed to wither away-presumably into parish bingo halls.

In fact, the California missions mostly did wither, during the emphatic secularization of the Mexican Revolution, when these empire outposts were seized, their assets stripped, and the adobe buildings left to melt in rain or California quakes. Just before that happened, however, they were captured in a series of 1883 engravings by famed illustrator and longtime Santa Barbaran Henry Chapman Ford. Ford rode on buckboard to sketch and then render the missions into prints. After appearing at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, his images inspired mass grassroots mission reconstructions: The moldering churches such as our own Queen of the Missions became Catholic parishes as well as tourist destinations-not to mention memorials to tens of thousands of California’s native people.

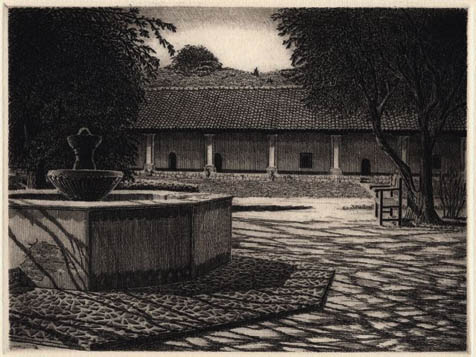

Ford’s once-inspirational visions are currently on display in the hallways of the county administration building’s Channing Peake Gallery, where they hang alongside prints made by contemporary Lompoc artist Leonardo Nu±ez. In Ford’s prints you sense an implied narrative, the abandoned ideal already swept aside by its society. The images stand in harsh, washing-out light. It’s hard to imagine them inspiring love and reconstruction. Next to Ford’s harsh eye, Nu±ez’s work seems utterly romantic. The same walls are deeply shaded, and the lines admit the interruptions of large yucca plants, softer forms inferring an organic restfulness.

It’s a little weird to see these images here in light of recent debates concerning the missions’ role vis- -vis the separation of church and state. On the other hand, even hung in political halls, these images seem a bit cliched. In this mild juxtaposition, the missions serve more as decoration than as stirring monuments to tremendous hope or fearful cruelty. Even the padres thought they would fade away, but apparently, as this exhibition implies, they are too pretty to disappear, despite the forces of earthquake, politics, or even history.