Charles Enoch Huse lived in Santa Barbara from 1852 until 1885. His journal, published by the Santa Barbara Historical Museum in 1977, offers a detailed and fascinating glimpse at Santa Barbara in the 1850s, as the city went through a sometimes troubled transition from Mexican to American rule.

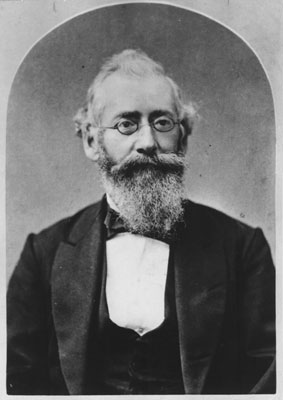

Huse was born in Massachusetts in 1825 into the family of a wealthy tobacco merchant. A bit of a wunderkind, by the age of four he was doing long division; and at eight he was reading Virgil and Homer in their original languages. He went on to attend Harvard, and by the time he graduated in 1848, he was fluent in Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, German, and Italian. His classmates voted him class poet. After graduation he taught himself law, which would eventually become his primary profession.

In 1849, Huse and his brother William set out for the California goldfields. Discovering that mining was not really for them, they settled in San Francisco and invested in real estate and various other business ventures. Huse also opened a legal practice. In October 1850 he was sentenced to six hours imprisonment for tampering with a jury, a transgression that was not all that uncommon in those days of frontier justice. Still, it would not be the last time that his ethics would be called into question.

In the spring of 1851, a fire deprived Huse of most of his possessions, although he did manage to save his precious library. Perhaps this misfortune pushed him to relocate, in January 1852, to Santa Barbara.

He quickly made his mark. In April he was appointed County Clerk; he also performed the duties of Recorder and Auditor during this period. He was elected to the State Assembly in the fall and, from 1854 to 1861, would hold the office of district attorney four different times. His fluency in Spanish was invaluable in a town where that was the language of record. He worked closely with District Judge Joaquin Carrillo; the latter’s English was quite poor, and Huse proved invaluable to the jurist.

Yet, by and large, Huse considered Californios politically and socially backward and thought their indolence was retarding city development. Part of this was religious. Huse was a staunch Congregationalist, and he was shocked that the locals would dare to indulge in various amusements on the Sabbath. At the same time, he greatly admired and respected members of the De la Guerra, Carrillo, and Covarrubias families.

Huse was a civic booster. He helped found the Congregational church here, the first public elementary school in 1855, and Santa Barbara College in 1869. He was a director of the Santa Ynez Turnpike Company, which built the stage road over the mountains, and in 1876 penned a booklet that extolled the virtues of the South Coast.

In his law practice, he did not always exhibit strong ethics or good judgment. He convinced W.W. Hollister that the title to his beloved Glen Annie ranch in Goleta was secure; the Hollister family would eventually lose the land after years of bitter legal wrangling. In another case, Huse attempted to gobble up valuable lands in Santa Barbara and Montecito on very shaky legal grounds, which so outraged the populace that a small riot broke out in front of his home.

By the early 1880s, Huse began to neglect his business ventures. He became inreasingly erratic, his irrationality slowly turning into insanity. He heard voices telling him he was ruler of the world. He was committed to an asylum in Napa in 1885. He died in 1898. One last time, he made the journey from the Bay Area to Santa Barbara-he was buried at Santa Barbara Cemetery.