Georges Rouault’s Miserere et Guerre: This Anguished World of Shadows.

At Reynolds Gallery, Westmont College. Shows through October 18.

This exhibition of prints by the 20th-century French artist Georges Rouault revisits a question that has fruitfully occupied the art department at Westmont College for many years: “Is modernism in art compatible with Christian devotion?” Rouault’s magnificent work answers the question with an emphatic “yes,” and anyone with an interest in modernism, printmaking, the Passion of Christ, or social justice ought to see it. Despite the apparent incongruity of a devout man like Rouault associating with the French playwright and provocateur Alfred Jarry-author of the satire “The Passion Considered as an Uphill Bicycle Race”-the power and the impact of Rouault’s work come precisely from the confluence of Christian faith and the modernist taste for creative destruction and upsetting the bourgeoisie.

Rouault was born into a poor family in the Belleville neighborhood of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War at the end of the 19th century, and he lived and worked in the city through both the first and second world wars. Apprenticed at age 14 to a stained-glass maker, Rouault attended the cole des Beaux-Arts alongside Matisse. His mentor there was the Symbolist Gustave Moreau, and the influence of this early master of intuitive self-examination and personal mythmaking never left him. Encouraged by Moreau to look inward at the same time that his day-to-day life was saturated with the suffering of poverty and war, Rouault drew early and often on the subjects he had learned about while working on the stained glass in Parisian cathedrals, especially the Stations of the Cross.

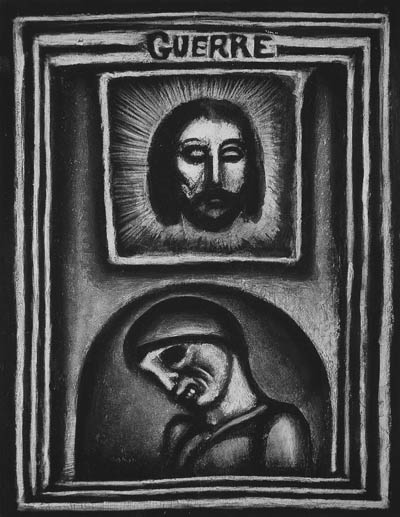

The black-and-white prints on exhibit now at Westmont were originally commissioned by the art dealer and publisher Ambroise Vollard, who asked for a series of 100 prints on the topics of Miserere-which is from the biblical Latin Miserere Mei, or “Have mercy on me”-and Guerre-“War.” Although Rouault never finished all 100 prints, and his relationship with Vollard deteriorated to the point where he bought the rights to his own work back from the dealer, the process of printing these large images came to occupy Rouault’s creative and religious life for several decades. His meticulous work habits resulted in a process that required huge amounts of time painstakingly spent adding specific details to the plates and running as many as 15 tests before printing. The intricacy of Rouault’s technique is such that even scholars are unable to completely reconstruct the multiple methods employed and their sequence. The wonderful catalog that accompanied this exhibit’s initial incarnation as a larger show at the Museum of Biblical Art in New York includes an excellent essay by MOBIA curator Dolores DeStefano on the various processes involved.

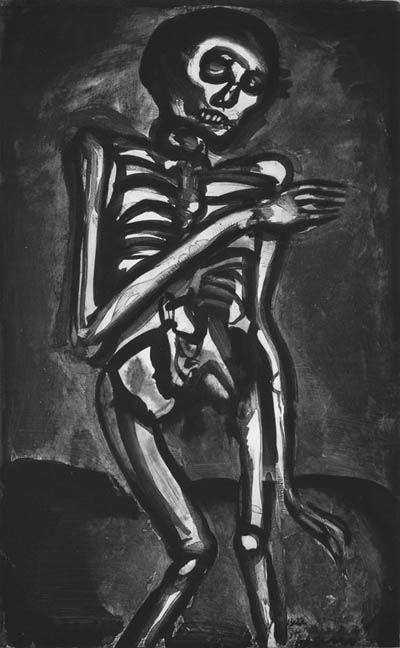

Although the “how” of this series may stymie even the experts, the “what” and the “why” of this work will be immediately apparent to anyone who sees it. The artist has contrived a method that allows black-and-white prints to glow with the inner light of stained glass and ripple with the atmospheric brushstrokes and washes of painting. The style is deliberately simple, but the rigorous logic of its conception and the infinitely patient authority of its execution result in something deep and powerful. The series is concerned with three types of humanity: the bourgeoisie, who are depicted as vicious and deluded; the poor and outcast, who are seen as ennobled by suffering; and Jesus Christ, who is the archetype and the analogue of both the artist and his beloved outsiders.

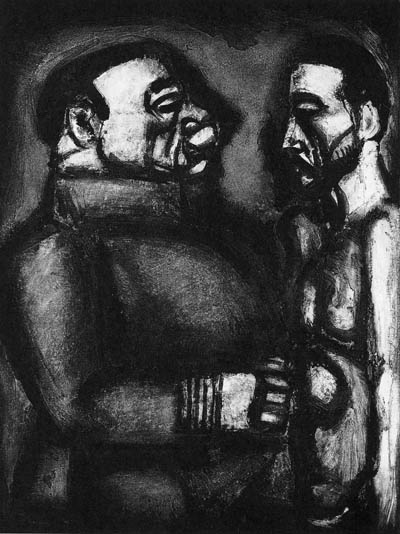

Like the great neo-figurative Colombian artist Fernando Botero, Rouault uses the device of the “ignoble double” to provoke and dismay the bourgeoisie. Botero employs the trope of engordesismo, or “the fattening up of things” to give his bourgeois subjects their just desserts, while Rouault portrays his self-satisfied corrupt judges and wicked generals as trapped by the masks that their worldly success has saddled them with. In Plate 40, “Face to Face,” Rouault interprets the verse (27:22-24) in Matthew where Pontius Pilate washes his hands of the blood of Christ. Rouault places Jesus gaunt abdomen-to-bloated belly with a 20th-century fascist type straight out of German Expressionism. The overall impact of Rouault’s strategy of interpolating the crucifixion within modern life is profound, and more so for being entirely matter-of-fact. Confrontational to the point of discomfort, the strategy tests our ability to compartmentalize religious and secular images of suffering.

As a young man, Rouault accepted an assignment that involved attending criminal court in Paris for many days in a row and recording what he saw there. His experience of the corruption of the French courts and the abject desperation that led most of the poor defendants to their crimes left him with little patience for outward displays of correctness and authority. For Rouault, the mystery and significance of the Passion of Christ derives from the way it celebrates the inadvertent consequence of a miscarriage of justice. Jesus may not have deserved to be crucified, but without his suffering there would be no hope of eventual redemption for all those ordinary people whose lives are distorted or destroyed every day by war, corruption, and greed. Christ’s act of ultimate self-sacrifice became for Rouault the only adequate answer to the painful existential questions raised by urban poverty and modern warfare.

In a poem he wrote to parallel this series, Rouault described his fate as an artist, which he felt was to live each day in suffering, as though he slept on a bed of nettles, until such time as he was called to the next life. The stanza in which he imagines his own death includes the benediction, “Tomorrow will be beautiful.” Rouault not only believed that his faith would allow him everlasting life; more importantly, he left this world convinced that even without his presence in it, the vale of suffering and sorrow we all inhabit remained the most beautiful thing we could ever know.

This is a major exhibit that reintroduces a crucial episode in the ongoing evolution of humanistic European culture against the forces of death and destruction that continue to be unleashed by militarism and social injustice well into our new century. Along with such other 20th-century French prophets of Christian social responsibility and mercy as filmmaker Robert Bresson, philosopher Jacques Maritain, and novelist Leon Bloy, Rouault represents the best kind of socially conscious religious art-the kind that knows its own limitations and lives in the hope of becoming worthy to witness the lives of the least among us. As his friend, the poet Andre Suars, wrote to Rouault about the way the artist depicted the poor and the oppressed, “The beautiful style with which you have dressed them is a guarantee of their souls, and that their misery is worthy of salvation.”