East Meets West

Theories and Speculations About the Origins of Western Palmistry

Remember earlier I mentioned that there are at least two palmistry traditions; Eastern and Western. A relationship between those two traditions has existed historically as well. It turns out not everyone believes that the Gypsies brought palmistry to the West.

According to Fred Gettings (Book of the Hand; Hamlyn, 1965), the earliest reference to palmistry in Indian literature appears in the Vasistha, Rule 21. There, an ascetic is forbidden to earn his living by explaining omens, or by engaging in astrology and palmistry. The Ancient Code of Manu, also Vedic, upholds similar principles.

Yet, in later times, palmistry became highly regarded in India. Palmistry was considered so important that the hands of gods in paintings and sanctuaries were carved with markings of lines and symbols. They were highly exaggerated, and not very similar to real-life palms.

Trade was open to the Greeks through established routes used by Arabs for centuries. What became Western palmistry traveled East. Alexander the Great, a pupil of Aristotle, is conjectured to have brought interest in the art back. Lines appeared on the palms of Greek statues of gods as well.

However nice this theory sounds, I would be remiss not to point out that Ancient Egyptians, Chaldeans, Sumerians ,and Babylonians all have been credited with originating the art as well.

A few months ago I even received an email from an Independent reader in Thailand who suggested that palmistry began with Native American tribes in the US. My reader suggests that Carl Jung wrote the forward to the book by Julius Spier, The Hands of Children, and was remiss in not mentioning that Erich Neumann‘s wife was an internationally know palmist. Jung took an interest in palmistry, the reader points out, and regarded Neuman highly, but didn’t in all his letters or books mention his wife reading hands.

After writing to point this matter out, the reader continued:

After traveling in Mexico and Europe and Asia I came upon something amazing I want to share with you. The Navajo Indians read hands; just the fingertips. They called them the “Holy Whorls.” To the Navajos, they were “wind prints” not “fingerprints”, as this is where the wind (life force) entered your body. By reading these prints it enabled you to see someone’s life force and their character…. it’s amazing that after nine years of reading and traveling, I have never heard about the Navajos reading hands. It was by accident [that] I stumbled on it. The Hopi Indians read the prints the same way.

For more on this theory of origins, and yet another tradition of interpretation, see the book Holy Wind in Navajo Philosophy by James Kale McNeley.

Whatever occurred in the New World, you can see European manuscript pages from the fourteenth century on display in the British Museum, if you ever get around to it.

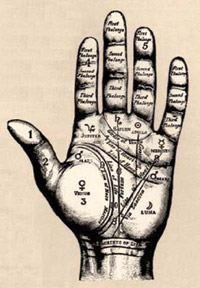

In the Western tradition, the art evolved from basic lines, to hand shapes, to texture and markings. Medieval writings focus on the lines. By the sixteenth century, the spirit of individuality was emerging. Early Renaissance scholars were often well versed in palmistry, and markings for different kinds of patterns were devised. The practice, still thought of as an art, was closely connected to astrology. Each finger and mound was related to a planet. It was thought a whole constellation of one’s life could be read in the thumb.

So, when you go in for the art of divining, be sure you get your money’s worth. The whole story is not told in the lines.

Like the history of trauma, the history of palmistry is buried underground and often veers off course. Its development has not unfolded in a linear fashion. In England, palmistry was not pursued with the same intensity as it was elsewhere. Chiromancy was primarily associated increasingly with the gypsies. Universities did not pursue its scholarship and practice, as did institutions of higher learning on the other continents.

If the gypsies came from the Pariahs of India, as some maintain, this would mean an alternate route of dispersion of Western knowledge. Traveling from shire to shire in the 1500s, they performed all sorts of crafts to get money from the landholders; palmistry being one such craft. But a practitioner among the lower classes was considered to be either a gypsy or a witch, thus the practice of palmistry merited death according to a law that was not repealed in England until the reign of George III.

Batya Weinbaum has been practicing as a palmist since the 1980s. To get your palms read, call 216 233 0567.