Zaca Fire May Be In Final Stages

Two Areas Left to Contain

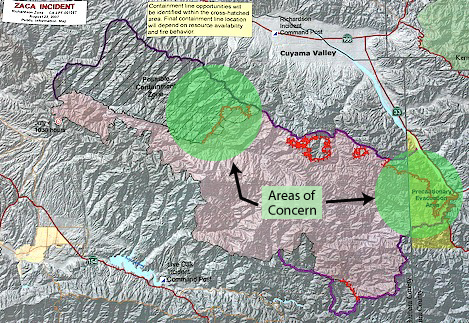

With final containment achieved on the Live Oak side of the fire, fifty-eight days after it began, fire officials turned their attention to the Richardson Zone.

Two areas concern operations leaders at the fire camp in New Cuyama: along Highway 33, they need to “turn the corner” at Ozena Station and hold the line five miles north in Brubaker Canyon; and deep in the heart of the San Rafael Wilderness, the fire continued to move slowly in the Sisquoc River drainage in an area more difficult for the crews to access.

Several nights ago Richardson Zone fire fighters faced their greatest challenge along the switchbacks just north of Pine Mountain at the point where the road drops down into the Cuyama Valley. With steep hillsides, narrow sections of road, and tall conifers that could spread the fire along their crowns, dozens of engines, water tenders, and hot shot crews were employed along the road to catch any spots.

The most critical point was at the longest of the switchbacks where it was impossible to allow the fire to burn into it. “The switchback is more than a half mile deep and it is almost straight down to the bottom half of it,” one of the Ops leaders explained. “We really needed to cut off that finger.”

To do so, hot shots cut a 10-foot-wide hand line down a slope in excess of 80% straight down the the lower road. Not sure the line would hold there, hose line was extended uphill on the other side of Highway 33 just it case the fire moved across the road.

With the skill they’ve demonstrated throughout the fire’s two month history, crews were able to hold the line, though at several points they did need to scramble up and catch spot fires that had gone across the road.

With this section of Highway 33 secured, fire fighters turned their attention to the remaining section that needed to be backfired – a five mile long piece stretching from Ozena Station north towards the small town of Ventucopa and to an inconspicuous side drainage known as Brubaker Canyon.

Starting yesterday afternoon from Ozena, as crews lined the road to check any escapes, several small helicopters outfitted with 150 gallon tanks of highly explosive accelerant began to lay down strips of what looked like streams of fire.

Beginning just below the crest of each ridge, the pilots would contour along the hillsides, setting long lines of the tinder-dry vegetation on fire. As the flames moved uphill, they would lay down a second line a but further down the hill, then a third even further down, allowing each strip to burn up to the other.

Moving progressively to the north towards Brubaker Canyon the hillsides began to fill with fire and smoke and within the hour the entire sky had turned an intensely beautiful mosaic, shades ranging from a creamy white to deep browns.

The backfiring was what one of the Division Supervisors called “textbook” – with the wind moving towards the south and the helicopters progressively moving the fire north, the flames were continually being pushed back towards the already burned areas.

By late afternoon yesterday, all that remained to control this section of the fire line was what the safety officer at Brubaker Canyon called a “tough two miles.” By 5pm the fire was being brought down into the canyon at a snail’s pace and allowed to burn uphill towards Tinta and Rancho Nuevo canyons.

As of late this afternoon, Operations Leader for the Richardson Zone, Rich Olsen, confirmed that the winds continue to be a bit too erratic to finish the backfire there.

Sisquoc River Frustrations

For the past week, Incident Commander Mike Dietrich and his ops leaders puzzled over strategies for dealing with the fire down in the Sisquoc. Since the day the fire rushed up over Mission Pine Basin and down into Big Pine Creek it has moved stubbornly downriver into areas that were impossible to get hand crews on the ground.

The plan that Dietrich felt had the best chance of success was building a combination of dozer and hand line down a seven-mile ridge called the Sweetwater. Despite the best efforts they were not able to hold the line.

In the most bizarre of circumstances, it now appeared the fire might pull off an almost impossible feat: to follow a path up one side of the wilderness, circle around San Rafael Mountain, then pull a major U-turn, reverse course, and end up 30 miles back downstream where it first crossed the Manzana on July 7.

Because the eastern end of the fire in both the Richardson and Live Oak zones were of such high priority, little could be done at that time; what the Richardson command hoped was that they’d have a few days where the fire didn’t burn too much before turning their attention back to the west end.

They got lucky. Over the next few days the fire barely budged, doing what the fire fighters called “nibbling its way” up the hills.

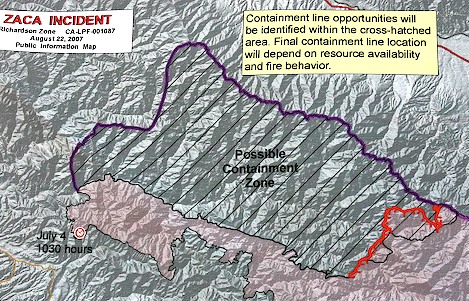

New Strategy for the Sisquoc

While the fire was stalling out, a number of things happened that favored a new look at the Sisquoc. First, with the fire nearing containment on the Live Oak side, resources were being made available for the Richardson side that weren’t there just a few days ago.

More air support was also becoming available. In addition, hot shots had come back in from the Pendola area, gotten some much needed rest and were being moved over to the north. Crews such as the Vista Grande, De Rosa, Texas Canyon, Fulton, and Tallac were now on their way. Local Los Padres Forest personnel were now coming over from Live Oak to help out.

One of these was Mark von Tillow, a fuels management specialist from the Santa Barbara Ranger District. His job as Branch Director for the western section was to take a fresh look at the fire to see what could be done short of watching it burn all the way down to the far end of Hurricane Deck.

Flying the fire line late on Tuesday afternoon, von Tillow was startled to see how much the fire had laid down. “There were barely knee high flames along parts of the line and in places it had gone out completely,” he commented. “I was thinking, we don’t need to find a ridge further down canyon. We can go direct right on the fire line and get it before it goes any further.”

The next morning Ops had InfraRed specialist John Neumann fly the fire line. He reported that there wasn’t much heat – backing up what von Tillow had seen the night before. As the day progressed von Tillow flew the fire line three more times, each with a different person, to see if they saw the same possibilities he did.

By late afternoon, operations had given von Tillow permission to move ahead with the operation and by dusk several of the hot shot crews had been flown in to ridgetops to spike out. “We put them about half way down to the river on points that had already burned. They were perfect for early attack.

“We’ve got a couple days with the wind moving straight up the river,” von Tillow explained to me last night. “That will keep the fire from moving downstream. There are only one or two small canyons we need to get across and the rest of it is ridgetop that’s either rocky or got hardly anything growing on it.”

By late afternoon, it appeared the hot shots were making good progress. “We’re feeling a whole lot better today than we did yesterday,” Rich Olsen reported. The hand line is almost down to the river and we’ve flown in crews to the Hurricane Deck area near White Ledge to begin building line down from there.

“With the additional hot shot crews we were also able to drop down from the crest too. One of the advantages of going direct is that we can put hose down the line as well. With engine crews and water tenders on top to provide the water, we put almost 5,000 feet of hose along the fire by 4pm.”

More tomorrow after I visit with Mark von Tillow up on the Sierra Madre crest and get a better feel for how things are going.