Showdown Over Wide

Open Spaces

Farm Futures

This year, for the first time in human history, more people will live in urban areas than in rural lands. Though the tipping point will most likely be reached-or perhaps already has been-without fanfare, its significance cannot be overlooked. With this new age comes a whole new set of rules, values, and views that threaten to leave many of our most celebrated traditions behind as we work to reconcile past methods of survival with a less agrarian lifestyle. Here in the United States, with the ever-growing beast of urban sprawl spilling from cities toward the horizon, the rural, agricultural spaces that were the societal backbone of previous generations are fast becoming zigzags of highways connecting suburbs to shopping centers. This is not to say that agriculture is dead, but as time passes, the people doing the hard work of growing our produce and raising our cattle are becoming fewer and fewer, their lifestyle incompatible with the slow and steady mastication of development.

Thank the Williamson Act

Right here in Santa Barbara County is a storied and vital community of ranchers and farmers with their backs to the wall, doing daily battle with drought, soaring land values, and developers clutching checkbooks in their smooth, uncalloused hands. Say what you will about movie stars, pretty faces, and red tile roofs, but Santa Barbara is and always has been an agricultural town. Beyond the glitz of State Street and its restaurants and world-class shopping lies a massive patchwork of rangeland, open space, and centuries-old farmland, every acre of it currently in a fight for survival. Last year, just as it has been every year since the Mission bells first rang, the agriculture industry was the number-one money earner in the region, bringing in more than a billion dollars to our local economy. From grapes to avocados to cattle, the land provides for the county in a way that film festivals, revamped State Street sidewalks, and oceanfront dining can only dream about.

While the drama of developers versus agriculturists has played out through much of the Southern California landscape, here in Santa Barbara County the march of development has until recently stayed away from much of our interior and northern boundaries. No doubt fortified by the hard work of families-many of whom have been working their land for generations-and extensive zoning regulations, the single best tool Santa Barbara County has had against the invasion of the newly built is the Williamson Act. Created in the 1960s, this state-run program offers massive property tax breaks to cattle ranchers and farmers in exchange for their surrender of certain development rights on their property. With nearly three-quarters of all the privately owned open space in the county protected under the Williamson Act, residents can thank this legislation for the soul-stirring views they enjoy each time they get north of Winchester Canyon or east of San Marcos Pass.

Administered by the state’s Department of Conservation (DOC), Williamson Act contracts-which landowners enter for 10 years at a time and have an annual option to extend-get the nitty-gritty of their enforcement from county-issued codes called the Uniform Rules. Each county has a choice about the particulars of its own rules, which dictate what constitutes acceptable development of Williamson Act land. Right now, for the first time since 1984, Santa Barbara County is engaged in a particularly brutal battle to update said codes.

Ironically, despite the fact that all parties involved agree that the Uniform Rules need an update to reflect the many changes in local ag since the 1980s, the approval process for the revisions has stalled indefinitely. Superficially, this delay seems to be the work of South Coast enviros, but upon further investigation the gridlock appears also to be a side effect of a much deeper rift within the ag community.

Growing Houses?

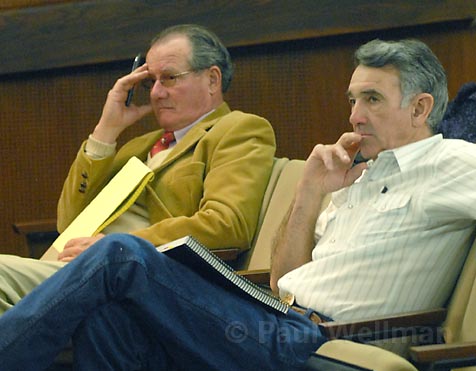

As you read this, lines are being drawn between a tight-knit network of families who have known, loved, and worked with one another for generations. On one side are influential and well-known ag folks like former county supervisor Willy Chamberlin and longtime local farmer Bill Giorgi, who-along with real estate lawyer Susan Petrovich and COLAB talking head Andy Caldwell-favor a slightly more development-minded approach to the future that would sacrifice portions of traditional ag land in order to increase the value of the remaining open space and keep pace with the boom of urban growth. With seats on local ag advisory boards and a fairly high public profile, they have been lobbying for a revamping of the Uniform Rules as a means to further their ideas about how best to protect our community’s agricultural future. Publicly, they claim they have the unfailing support of their fellow aggies.

Opposite them, however, is an increasingly vocal faction that sees the increased development options currently being explored at the county level as a guaranteed death blow to anyone who wishes to stay in ag by more traditional means. In the past, this side has-for fear of ruffling longtime friendships and upending general vows of solidarity- remained quiet. Of note, fewer than a dozen of the hundreds of Williamson contract holders in the county turned out to speak in favor of the proposed Uniform Rules updates during the many public hearings on the subject in the past eight months. Easily the single biggest demonstration of this rift has been the silence of the Santa Barbara County Farm Bureau-arguably the largest and most powerful assemblage of agriculturists in the region-during the ongoing debate regarding revisions to the Uniform Rules. But it seems the breaking point has come in recent months, as vibrations from this split have been rattling behind closed doors at Santa Barbara Cattlemen’s Association meetings and at public hearings of the county’s various ag agencies. Commenting recently on the subject, Farm Bureau Executive Director Teri Bontrager said in a noticeably guarded manner, “We have very specific policy on the Williamson Act and we have to follow it : We wouldn’t want to do or say something that we wind up regretting.” Then, when asked about the ag community’s general feeling about the specifics of the proposed updates, Bontrager said something far different from the public testimony of Chamberlin and Giorgi, the latter of whom sits on the bureau’s board of directors. “There is a lot of concern out there about it,” she said of the proposed changes.

The ongoing debate about our county’s attempts to update its Uniform Rules provides a handy entry point to understanding the trouble brewing. After a 2001 audit by the Department of Conservation found the local rules to be woefully in need of a revamping, the bumpy road toward policy reform began. Formed specifically for such ag-minded endeavors, the county’s Agricultural Advisory Committee (AAC) and its Agricultural Preserve Advisory Committee (APAC) were charged with the task. However, at that time, some folks within the farming and ranching community felt the AAC didn’t have the best grasp of the real issues facing them and as a result, these parties worked to influence the public committee’s policy-crafting. Perhaps the most vocal of these factions was the Santa Barbara Cattlemen’s Association and its Land Use Committee. Speaking recently, committee chair Andy Mills recalled, “In the beginning the AAC wasn’t really functioning properly and-this probably won’t sound good-but we decided that maybe we should feed them some issues and our ideas.”

Luckily for Mills and the 100-member-strong Cattlemen’s Association, two of the men who helped craft the organization’s recommendations in private at the Land Use Committee level, Chamberlin and Giorgi, also sat (and continue to sit) on the public AAC. In fact, Chamberlin and Giorgi are the AAC’s respective chair and vice chair. So when the Land Use Committee pitched its ideas to the AAC, it had, at the very least, two sympathetic sets of ears on the board. Moreover, in 2005, when the Uniform Rules update was passed along to the APAC for further fine-tuning, Giorgi and Chamberlin were appointed as the lone agricultural representatives to that seven-member board once again, bringing to the table ideas they themselves helped hatch years before at the Cattlemen’s Association. The result, at least in the eyes of longtime cattle rancher and Williamson Act contract holder Jim Poett-who, in the spirit of full disclosure, is the husband of Independent editor-in-chief Marianne Partridge-bodes ill for the future of ag. “You end up with the same small group of pro-growth people making these very significant decisions about land use time and time again,” Poett said.

Positions of Influence

Given their role in developing the proposed changes, their experience in local ag land-use policies, and the fact that both come from longtime Santa Barbara County farming families, it surprised few that Chamberlin and Giorgi spoke most favorably about the Uniform Rules updates when the proposal finally reached the county supervisors’ agenda late last year. Along with fellow Land Use Committee visionary Caldwell and a smattering of other Williamson Act contract holders, they warned that local participation in the program was waning and certain development-friendly allowances had to be made in order to keep the program viable. “Without a doubt, the Williamson Act is the best land conservation tool we have,” explained Chamberlin. “But agriculture has changed a lot in the 30-plus years since the program started, and we need to give farmers and ranchers more incentive to stay in their contracts.” Without changing any existing zoning, those proposed incentives include the ability to build as many as three family residences on contracted lands larger than 100 acres (as opposed to the one family home-per-contract currently allowed), the running of guest ranches or guest farms on contracts larger than 40 acres, and the expansion of allowable ag support facilities for activities like processing, cooling, and composting. It should also be noted that the proposed updates far exceed in both scale and scope the technical changes mandated by the DOC’s audit, a fact that was highlighted by a letter of concern from the DOC to the county last year.

With county supervisors Joe Centeno, Joni Gray, and Brooks Firestone all in support, the updates seemed destined for a slam-dunk approval late last December. In mid February, however, South County environmentalists and North County critics-their eyes on two dozen other policy projects currently under construction by various county agencies that could possibly impact development on ag land-derailed the process at the last minute by forcing a comprehensive Environmental Impact Review (EIR) of all the potential policy tweaks in the works. Additionally, critics successfully cried foul on the fact that Firestone owns several hundred acres of Williamson Act land that could potentially enjoy economic gains from the updates. Consequently, at the behest of the county counsel, the 3rd District Supervisor begrudgingly recused himself from all future debate on the subject due to this perceived conflict of interest.

Williamson Act Dropouts?

Then there is the vast difference between the pollings of public opinion by Chamberlin et al and the aforementioned remarks by the Farm Bureau’s executive director. Besides demonstrating the degree of the fissure in the upper levels of the ag community, these distinctly different observations become a possible indicator of more insidious dealings when viewed in light of the fact that the primary motivation stated for the updates during the county supervisors’ hearings was a decline in local enrollment in Williamson Act contracts. Even Supervisor Firestone claimed, “It is clear that the Williamson Act is slipping, and we have to stop that.”

Quite to the contrary, according to documents from both the DOC and the county Assessor’s office, the amount of Santa Barbara County acreage enrolled in the program has remained more or less the same for the past decade. While this number, which is currently 549,278 acres and was 539,043 acres in 1996, can be misleading because it takes contract holders 10 years to phase out of the program, one need look only at the annual subvention reports submitted by the county each year to the DOC to see the extent of phase-out initiation. Upon examination of these documents, it is obvious that, with the exception of 2005 (when the Bixby-Cojo Ranch filed to pull several thousand acres in order to facilitate their sale), the number of acres being removed from the program has been minimal. In fact, Lisa Hammock, who oversees Williamson Act contracts in the Assessor’s office, stated last month, “There really hasn’t been much of a change at all. We just aren’t seeing very many people getting in or getting out of contracts.”

Despite this, a county staff report in the days leading up to the December hearings rang an alarm about declining enrollment, claiming some 44,000 acres will be pulled out in the next decade. Of that number, more than half is accounted for by the Bixby-Cojo withdrawal, a point which since appears to have been rendered even more irrelevant as all indicators point to the new owners re-enrolling the property. Alluding to this misinformed line of logic and to the fact that a select few like Chamberlin and Giorgi, who both own thousands of acres of Williamson Act land, have had such a major role in shepherding the decidedly development-friendly Uniform Rules updates, 1st District Supervisor Salud Carbajal commented last week, “All of it undermines the integrity of the decision-making. And whether the conflict of interest is real or perceived, it still kills the public’s trust in the process.”

To Recuse, or Not to Recuse

To Bob Field-a former Firestone appointee, onetime head of the Santa Ynez Valley Plan Advisory Committee, and leader of the mini-revolution that forced the additional EIR of the Uniform Rules updates-there is no question about the conflict of interest for Chamberlin and Giorgi. At an APAC meeting on July 13, Field took the opportunity to levy the same charges that forced Firestone’s recusal on the subject against Chamberlin and Giorgi. In his opinion, the fact that Giorgi-who owns roughly the same amount of Williamson Act land as Firestone-and Chamberlin-whose family owns eight times more-sit on a county committee whose sole purpose is to deliberate on all things related to the Williamson Act becomes a blatant conflict of interest because the proposed rule updates could result in financial gains for them.

Furthermore, Field contends the two men were never legally approved as the agricultural representatives on the seven-member APAC panel, as they were appointed by the AAC in late 2005 but were never officially approved by the Board of Supervisors, which was purportedly the entity that should have had final say in who makes it on to the APAC. “All I am asking is that if any reasonable person doesn’t think this behavior passes the smell test, then why don’t they just take themselves out?,” Field said. “It is the honest thing to do.”

Though very much in the preliminary stages, Field’s latest claims appear to have some legal basis and are currently being investigated by Deputy County Counsel Mary Ann Slutzky, who said she is recommending that APAC members adhere to the county’s conflict of interest code-which they have historically not done-and that she will file her findings in August. “I am not willing to say right now that they have to step down. But depending on what I find, I think we would have to look very closely at things on a case-by-case basis.” For their part, both Chamberlin and Giorgi feel that Field’s accusations are without merit as the APAC, in their opinion, is an advisory group without any real power; thus, conflict of interest charges shouldn’t be applied to them. According to Slutzky, it is the latter that is the specific premise of her investigation.

The People’s Voice

Regardless of the legal debate, the fact remains that two men-who critics claim are “pro-growth ranchers”-have had a whole lot of say in the discussions that generate agricultural policy in Santa Barbara thanks to the various boards, both public and private, they sit on. Furthermore, based on the anemic mailing lists of the APAC and the AAC-each of which numbers fewer than 100 people-their hearings, despite being public affairs, are rarely well attended or even common public knowledge, an arguably disturbing trend when one considers that nearly 90 percent of all privately owned land in the county is zoned for agriculture. Add to this the admission of Cattlemen’s Association land-use chair Andy Mills that “it is true that the core group who go to all the meetings of the Land Use Committee and wind up making the decisions is a very small one,” and the resulting situation, while far from being certifiably underhanded, seems potentially ripe for people of influence to push their agendas on the unsuspecting masses.

Chamberlin himself spoke recently about how he felt it was easier to resolve issues in the comfort of the Land Use Committee. “I am all for public input but there comes a time-and it has to be the appropriate time-for certain discussions on these topics to take place between people who have a knowledge and a history with it,” Chamberlin said, noting that he in no way supports doing business behind closed doors. Even the county’s Agricultural Commissioner Bill Gillette said of the Land Use Committee’s relationship to the AAC and the APAC, “At the very least, it is a good place for things to start.” By Mills’s numbers, the Land Use Committee mails out only about 20-25 notices for its monthly meetings despite the fact the Cattlemen’s Association-which must approve any decisions made by the committee-has a membership of more than 200 area ranchers.

Much in the manner that all involved parties agree that the Uniform Rules need to be modified, so too can it be said that everyone understands the supreme importance of having knowledgeable, lifelong agriculturalists like Giorgi and Chamberlin in positions of power. After all, as Giorgi himself put it, “Before Willy and I were put on the APAC, they didn’t know the difference between a hoe and a plow. They had zero background in agriculture.”

What seems to be in order-at least for the farmers and ranchers who view the current ag policy trends as being too much in favor of growth and development on ag land-is a balancing of power. While rumors have long swirled that just such an entity or committee is forming, the communion of said people has yet to occur. (The current climate, however, seems to indicate that such a meeting is imminent.) In the meantime, as Mills explained it, “Two groups of people who agree on 90 percent of the issues spend all their time and energy fighting over the 10 percent they don’t agree on.”

And while that happens, the county’s agricultural future twists in the wind, with a swarm of real-deal developers waiting to scavenge its fallen fruit.