East Hurricane Deck Loop-Backpack

A Four-Day Trip

Name of Hike: East Hurricane Deck Loop-Backpack: Lost Valley Trail to White Ledge Camp via Hurricane Deck Trail, return to Nira via Manzana Narrows (loop from Nira to Nira).

Mileage: 25-mile backpack across the eastern Deck on sometimes sketchy trail.

Maps: B. Conant’s San Rafael Wilderness Trail Map Guide (2009 ed.) and the two USGS 7.5 min. topo maps Hurricane Deck and Bald Mountain.

Suggested Time: 3.5 to 5 days.

This challenging backpack into the San Rafael Wilderness serves as a “bookend” adventure to an earlier backpack across the spine of the western Hurricane Deck, described in a February column. There are several natural obstacles preventing easy access onto the Hurricane Deck formation — which is essentially a gigantic, 17-mile-long sedimentary rock chunk forming the core of the San Rafael Wilderness.

The Deck’s southeastern face really allows only one way onto the rocky spine: ascending the picturesque Lost Valley Trail. Various readers and friends of this column have inquired about the intense motivation to return again and again to the San Rafael Wilderness and other remote barrens I’ve favored (e.g., Mt. Lassen, Dick Smith, Anza Borrego, Carrizo Plain, eastern Sierra). One could wax eloquent about the wild’s restorative powers and one’s need to eliminate nature-deficit syndrome. One might also symbolically compare the path into wilderness-ecstasy to the Lost Valley Trail — it’s the only way through to deep joy in the wild Hurricane Deck. It’s hard to follow and mostly without water; no water on the Hurricane Deck. Here we can look at the philosopher Charles Taylor’s profound thoughts as expressed in books like Sources of the Self (1989) and A Secular Age (2007). In A Secular Age, Taylor discusses what it means for a society, like our Western world, when belief in God is no longer commonplace.

He refers to the loss of moments like those described by Peter Berger when “ordinary reality is ‘abolished’ and something terrifyingly other shines through.” When we lose these transcendent moments (not all of them terrifying) and give everything up to the self-sufficient power of human Reason, we lose something essential to our psychological and spiritual health. Taylor writes about a “buffered” self, an identity that assumes a huge distinction between “the immanent and the transcendent.” The mundane blocked off from the sacred.

He asserts that “Naïveté is now unavailable to anyone, believer or unbeliever alike … Modern civilization cannot but bring about a ‘death of God’.” He means Nietzsche was correct in his corrosive critique of dead European Christianity — and look how the Pope appears so quaint. The salient point for hiker-fanatics is when Taylor shows how, for the modern, buffered self, “the possibility exists of … disengaging from everything outside the mind.” All experiences are felt from a distance, often on a tiny screen.

There are certainly many cases in which we can see the melancholia, nihilism, and depression stemming from loss of faith in the transcendent (and I do not mean faith in organized religion). These sorts of thinking today — existentialism, structuralism, postmodernism, posthumanism, gadget idolatry, aggressive atheism, moral relativism — tend to bludgeon us and our children into feeling all-mental all-the-time. In this wealthy country, with our democratic government, why is there so much depression and fear — fear about terrorists and pensions and jobs and pollution, and deep anxiety about the future our poorly educated children will face.

The once-porous boundary between ordinary social living and transformative experiences in nature has become a sealed Berlin Wall. Those who love to head out onto the remote trails are viewed as a little crazy or pretty “far out” — yet restorative, sparkling, divine nature awaits us after a 47-mile drive to Nira Camp in deep nature.

Arriving at Nira Camp, at the literal end of the road, millions of miles from Santa Barbara, my friend Chris and I were initially dismayed to see 14 cars and horse-trailers in the dirt parking area next to Manzana Creek. April 2 is a Monday, but apparently several schools are off for Easter/spring break, and some wise educators have brought their students into the San Rafael Wilderness (Dunn School is here for example). Nothing daunted, we do some quick limbering exercises, strap on our light backpacks (mine weighs 33 pounds), tighten shoelaces, stride east, and begin by fording robust Manzana Creek.

Our journey will lead up onto Hurricane Deck’s ridges of sandstone, where we will encounter strange rock formations; hard, thorny chaparral; and a myriad of yucca plants. Jan Timbrook has shown what an excellent food source the yucca root provided for the native Americans (A Chumash Ethnobotany, 2007), although we didn’t bake any on this adventure. Since Hurricane Deck is without springs, streams, or creeks, locating water will be our main exploratory activity.

We have four days to complete our loop, and this first day we trudge past gorgeous (and overcrowded) Lost Valley Camp, just one mile from Nira. Here we do not continue along the Manzana, but head north up well-marked Lost Valley Trail for about four miles — to the final place where we have reason to hope we can discover potable water. Where Lost Valley Trail becomes the squiggly lines of the map’s “horseshoe bend,” sometimes a thirsty seeker scouts about and divines a spring — this is Little Vulture Springs, and its characteristically sluggish flow means you should filter this water or at least boil it.

At the small potrero here with three mighty oak giants — survivors of several fires, we can see — we pitch our tents and fade out by 8 p.m. I’m not yet in backpacking shape, and legs and shoulders ache somewhat (ibuprofen helps).

Day Two arrives with splendid weather, the morning temperature around 45 degrees F, and we prepare for our most difficult day, an eight-mile backpack across the Deck. After one mile in the horseshoe-bend trail section, we water-up for the last time at tiny Vulture Springs itself, shown on Conant’s 2009 map. We experience awe in the presence of this pure, life-giving liquid. This water umbilicus comes straight out of our earth mother’s being. We’re still more than two tough, ascending miles away from the Hurricane Deck’s apex: the otherwise unremarkable spot where the Lost Valley Trail ends and we intersect the main Hurricane Deck Trail. It’s getting warm, and trail conditions are very poor, thus confirming Conant’s color change from yellow (good) to purple (substandard); we’ll have hiked up almost 2,000 feet from Lost Valley Camp at the apex.

Unlike our western Hurricane Deck backpack in February, once we reach the apex there isn’t any feeling of standing on the highest ridge or any Maslow’s “peak experience” grandeur. I discover the cool iron sign cast on the ground beside the rotted 4×4 post (and the later iron pole with bolt, also on the ground), and it’s the only reason we’re sure we’re now on the new trail. The sign sternly informs us that it’s 10 miles back to the Manzana. We labor over very rough ground for the next 4.7 Hurricane Deck miles — the trail is nonexistent in places so you bushwhack and make intelligent guesses, glad there are two hikers, acutely aware of meager water supplies. (I left Vulture Springs with 1.5 liters.) We are mesmerized by weirdly contorted rock formations.

Staying high up on the spine as much as possible is the credo. However, the 2007 Zaca Fire burnt through here, and the extraordinarily hardy chaparrals have sprung back in godlike fashion. This new growth also obscures the already vestigial trail. However, the last 1.5 miles is much better. We’re dropping down toward White Ledge Camp, and there has been some trail maintenance. As well, there are a few strategically placed bits of pink tape to guide us.

We can hear White Ledge Creek’s rushing water before we walk into the gorgeous camp of the same name and plunge immediately into the glistening pools. We’re lucky there are no campers here, and we settle in for the night. Every night on this trip I sleep like a child: very tired, full of awe, immersed in the Now, without cares, no fear.

From White Ledge, we backpack five easy miles away from the Deck to Manzana Narrows, a favored camp for many wilderness lovers. After two nights without access to a table, the wooden structures here at the Narrows make it feel like the Ritz Carlton, and the six-foot-deep pool made Chris forget himself and plunge straight in. We’re now in a riparian woodland ecosystem much different from the arid high desert above us — abundant spring flora like indian paintbrush, purple lupine, Chinese houses (Collinsia heterophylla), magenta prickly phlox, and many more provide glorious displays lining our path in this antediluvian cosmos. I came close to a rattlesnake at one point, but it slithered harmlessly away.

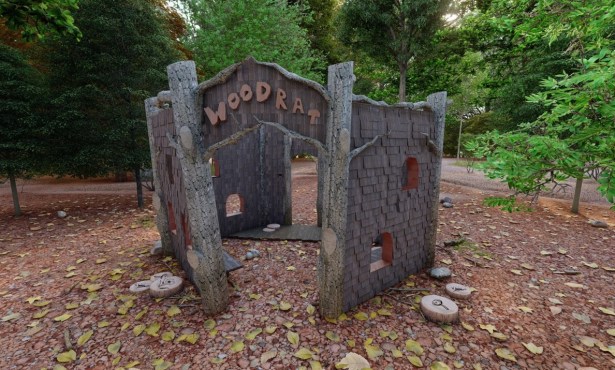

“The Narrows,” as we call it, occupies a deep cleft with several great pools to splash in with children. While fishing is now outlawed, you can see nine-inch trout here. There are four sturdy tables here along with four fire rings, and fairly often this camp teems with California Conservation Corps workers or the ubiquitous Boy Scouts. We chose to make no fires. We were again fortunate, and there was no one at the Narrows.

On Day four, our last day in true nature, we trekked the seven easy miles out to Nira paralleling the gurgling Manzana Creek the whole way — serenaded by bees, with noses teased by the fragrant ceanothus (California lilac), eyes delighted by golden poppies and purple lupine. I left an hour before my teaching colleague and enjoyed the entire three hours rambling down toward my civilization in solitude.

I don’t know about the loss of the sacred in town or in politics (!), but we can today repair our lost sense of cosmic sacredness by ritually returning to the wilder zones near us. This return could as easily be a stroll to the monarch butterflies at Ellwood as a 25-mile backpack into the San Rafael Wilderness. If we do not press the schools and “associations” to push into nature, we risk making access to nature — hiking into the sacred American interior — a way of life reserved strictly for an elite minority.