Integrated Math Curriculum to Replace Traditional Classes

School District Works to Weave Algebra, Geometry, Functions, and Statistics Together

Algebra will soon be a course title absent from Santa Barbara Unified School District catalogs. Students will still find the slope of a line using y = mx + b, but Tuesday’s school board meeting marked the first official transition toward integrated courses that weave algebra, geometry, functions, statistics, and probability into a yearlong high school math class, getting rid of traditional courses titles like Algebra 1, Geometry, and Algebra 2.

The State Board of Education finalized the framework for Common Core State Standards in November and gave districts the freedom to choose math course sequence, pathways, and rollout plan. Whether they choose the traditional or integrated model, all districts will have to realign their math courses with the new standards, which emphasize concepts over procedure and focus more on context and application and less on isolated skill manipulation.

Preliminary data indicates half of the districts in the state have chosen a traditional model and half have chosen the integrated one. Nearby districts, including Santa Ynez and Ventura, have opted for the integrated model. “The expectations and the testing is the same no matter which pathway you use to get there,” said Ellen Barger, director of curriculum and instruction at the Santa Barbara County Education Office.

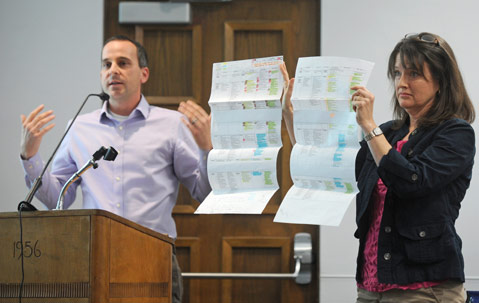

At S.B. Unified, teachers on special assignment Craig Schneider and Janet Hollister — both longtime math teachers — have spent more than a year researching the new expectations for math curriculum mandated by the state standards. At a special board meeting last month, Schneider explained to boardmembers that in the past when a student answered a problem correctly, he was unsure if they were able to correctly write a mathematical equation. Now, there will be “no guessing,” and students will be assessed on their ability to take answers and “work backward.”

Longtime and now retired math teacher Jerry Chui — who now works part-time for College Preparatory Mathematics, a nonprofit publishing company — explained that standards, teaching practices, and assessment all come into play with Common Core. “As I look at Santa Barbara, they are buying into the complete package,” Chui said, explaining that many districts are focusing only on assessment. But he said the technology side of the Common Core — level of equipment, proficiency of teachers, and access — could pose problems for the district. The new test Smarter Balanced — which will trial this spring and be fully implemented the next school year — will have both online and on-paper components. Educators hope this new test will provide students and teachers with a better, more-thorough assessment.

“The strongest hold for the teachers is to prevent ‘teaching to the test,’” Chui said, explaining multiple-choice exams facilitate that instructional method. “Common Core is basically getting used to a new system of delivery,” Chui said. “It’s just a big change.”

Hollister explained that the shift to the integrated model may be easier for senior teachers than for teachers who began teaching after 1997 because a reform math movement similar to the Common Core popped up in the 1980s and 1990s but failed to materialize.

“The ’97 standards assessment test became a very overbearing thermometer of success, and maybe schools lost sight and a passion for learning,” Boardmember Gayle Eidelson said.

At Tuesday’s board meeting, a couple of parents took to the podium to praise Hollister and Schneider’s hard work, but also called on the entire district to make sure higher-achieving students are still challenged in their math classes.

“A lot of parents are used to the traditional system,” Chui said, adding that some kids struggle with this different approach to mathematics, which has led people nationwide to be skeptical of the Common Core. But, Barger said, “the Common Core does not tell teachers how to teach,” explaining that people who claim to be “anti-Common Core” are actually opposed to the way their particular state or district has adopted it. “Change is difficult,” she added. “Teachers are going to have to relearn.”

What’s still to be determined for S.B. Unified — and was discussed during the conference portion on Tuesday — is which courses will ultimately be implemented. The board is expected to vote on that in two weeks when Hollister and Schneider return to the board with course descriptions and pathways. Current high school and junior high school students in accelerated math courses will continue in the traditional sequence. The 1,500 students entering 7th grade next year are the ones who will experience the most change as the program is rolled out over the next several years.

“It’s a pretty picture,” Hollister said referring to a rainbow-colored graph. “It’s a lot of work.”