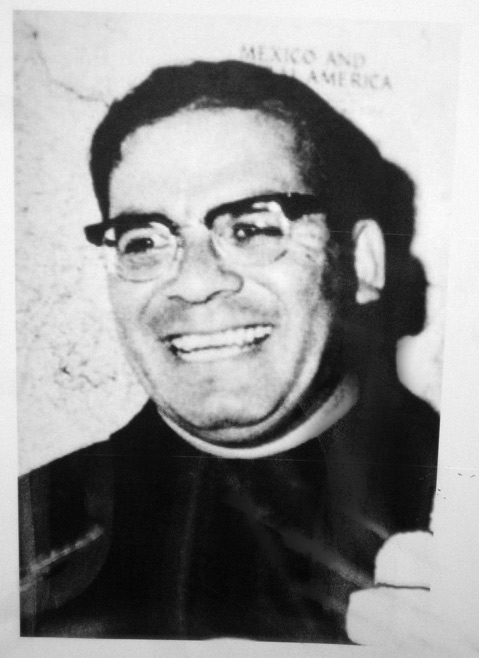

On November 23, 2013, the Franciscan priest responsible for molesting me and hundreds of other boys at St. Anthony’s Seminary in Santa Barbara during the’60s, quietly passed away in a California hospital at the age of 82. Mario Cimmarrusti committed crimes that made him one of the most notorious perpetrators in the history of the clergy sex abuse scandal. It’s fair to say that he was detested not only by his victims, their families, and the community at large, but by the majority of his fellow friars, most, if not all of whom, chose to ignore and alienate him during the last years of his life.

Many have argued that Mario got off easy. Over the years, and since the scandal first came to light in 1992, the Franciscans have paid out millions of dollars in damages to settle civil suits brought by those who suffered abuse at Mario’s hands. But due to the statute of limitations he never faced criminal charges. Dozens of survivors I know believe they were cheated by the legal system. The best of what they hoped for was stolen from them by a priest who got away with unspeakable sins. “He should have died behind bars rotting in prison,” one survivor told me when he learned of Mario’s death.” This bitterness has been echoed by many others.

It’s understandable. There was a time when I promoted my anger and cherished the safety and comfort it offered me, smug in the knowledge that I could openly hate someone like Mario so thoroughly and profoundly. It wasn’t until I entered therapy in 1994 that I recognized the great toll my hatred had taken on my life. The poison I had methodically prepared for Mario over the years had become a deadly concoction I was slowly drinking myself. This realization radically changed my thinking and my life.

As a result, I made a conscious decision to examine the question of forgiveness and what it meant to free oneself spiritually. From my earliest memories as an obedient Catholic school boy, I knew I was not interested in the church’s demands and conditions for forgiveness that only created more guilt and resentment. Instead, I pursued the concept of forgiveness that arose from a willing choice, and one that sustained an ongoing process.

I came to understand that forgiving Mario was not about Mario. It was about me. It was something I could ask and do for myself, not for him or anyone else.

Make no mistake: Mario Cimmarrusti had not been well for most of his life. In private sessions over the years with clinicians he made bizarre and fantastic assertions about his sexual past. These and other details are documented in files that were ordered by the court to be released to the public in 2012. But through my work with SafeNet, an organization I cofounded to support everyone’s healing, including the perpetrators, I was fortunate to establish and maintain contact with Mario.

Since 2003, and up until his death, he and I exchanged several letters and met privately on six occasions. I didn’t attempt this because of any traumatic bonding I was experiencing. I was in therapy at the time, and had been for some years, learning to move further and further beyond the reach of this man who hurt me. Rather, I felt a sense of purpose. And I think we both felt coming together was an act of compassion for ourselves and each other. When Mario died in November, he was living less than a hundred miles from me at an assisted living facility in Los Banos, after being transferred there last year from a facility in Missouri.

Although I initiated these unprecedented encounters — usually against the wishes of the Franciscan authorities who never knew what to do with their most infamous offender — none of these meetings would have occurred at all without Mario’s consent and assistance. Once, when I asked him whether or not he had been abused while a student at St. Anthony’s, he denied it but wanted to know why I asked. I told him my research over the years, which included conversations with former seminarians from Mario’s era (the ’30s and ’40s) including one of his own classmates, indicated that boys had been molested by Franciscans who held similar positions at the school which Mario would later fill (prefect of discipline, infirmarian, and choir director). He found all this intriguing, but he never said any more about it.

Eventually, I came to believe that Mario probably suffered the same fate as the rest of us when he, too, was a 14-year-old freshman at St. Anthony’s. None of this, of course, excuses his behavior or actions. But as I began to understand the trauma I experienced at the seminary, I clearly felt the torment he, too, must have endured there as a young boy. This small realization was an epiphany. My willingness to be present with the person who hurt me had allowed me to transform him from a monster into a human being.

Mario’s psychological state had always been a disaster zone. I believe his own secret wounds had festered for so long that they scarred the core of his memory until he lived almost entirely in a world only he recognized. His constant denials about the crimes he committed left him severely depressed and physically ill for most of his life. He was, for all intents and purposes, locked in a prison of his own construction. And yet, for all his many failings, Mario, like the rest of us, desperately sought to understand what had happened at St. Anthony’s Seminary long ago.

I don’t believe he ever managed to grasp the truth and shake the demons from his life. But every time we sat and talked, he made it clear to me that he was trying to comprehend what had taken place in his life and in the lives of the boys in his care. He never admitted doing anything wrong, and he always spoke of doing everything to help others. In his shattered state of mind it was inconceivable that he could have done the terrible things attributed to him. But Mario wanted to hear what had happened, not just to me but to others. When he asked me direct questions I often felt he was trying to square my personal accounts with all the horrible stories he had read about himself in the media.

The closest he ever came to accepting any responsibility was when he acknowledged that listening to my recollections might someday help pry open his own memories. It was the most honest admission he ever made in my presence.

On November 23, when a friar friend called to inform me of Mario’s death, I ran the gamut of emotions. The following day I placed a photo of him on my dresser and lit a candle. Instinctively, I pulled from the shelf a daily journal I kept in 1966 during my last year at St. Anthony’s. At 15 I had become deeply disillusioned about the priesthood as a result of my abuse the year before. I had no way of realizing this at the time or even naming it for what it was. It took years for me to understand that my decision to leave the seminary was fueled by what Mario had taken from me. Now, flipping through my journal, I came upon the date marked “November 23” and read the following entry: “Tonight I called home and told mom I decided not to return to St. Anthony’s after Christmas vacation. I feel sad but relieved.”

There is a certain measure of faith involved in the healing process. We wrestle every day with the ghosts of our dreams, but it’s the struggle itself that frees us. Perhaps the best of what we hoped for is somewhere in the worst of what we lived.